Bernard Porter

They Came, They Saw, They Dissented

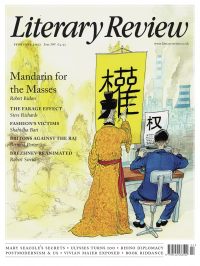

Rebels Against the Raj: Western Fighters for India’s Freedom

By Ramachandra Guha

William Collins 476pp £25

The history of British India is studded with examples of ‘treachery’ – or it might be better to say ‘disloyalty’ – on both sides. On the Indian side, there were the tens of thousands of collaborators who, for good as well as nefarious (but always understandable) reasons, enabled the Raj to persist as long as it did. On the other side, there was a significant stream of Britons who sympathised with Indian ambitions for self-rule, either within the empire or outside it, from the establishment of the Raj until 1947, when the ‘transfer of power’ to Indian hands – as it was called in order to make it seem more like a gift from Britain than a freedom bravely seized – took place. Among the latter were four Britons who, together with two Americans and an Anglo-Irish woman, are the subjects of this book. All of them became Indians, effectively, and were either imprisoned or deported by the British for their pains. Imprisonment and deportation are in fact two of the main criteria for inclusion here (otherwise there could have been many more). Another criterion is that the individual ‘contributed enormously to public debate’ on the nationalist side ‘within India’ and came to India alone. This excludes those whom William Dalrymple has called the ‘White Mughals’, who merely slotted into the Indian aristocracy and sometimes stayed on after the ‘transfer’, and also – perhaps curiously – those who were originally lured to India by love.

There are seven individuals who pass Guha’s tests: Annie Besant, half-Irish and a champion of home rule for that nation, as well as of socialist, feminist and religious causes in England before she sailed for India in 1893; Benjamin Guy Horniman, a powerful journalist and closet gay; Samuel Evans Stokes, an American Quaker who remained a Christian but disassociated himself from the patronising missionary Christianity he saw around him in India; Madeleine Slade, an upper-class English concert pianist (but apparently not a very good one), who dedicated her life to Gandhi after reading Romain Rolland’s book about him and setting sail for India in 1925; Philip Spratt, a Cambridge-educated communist who went to India in 1926 to organise the Indian workers in a more revolutionary and potentially violent way than Gandhi’s ‘bourgeois reformism’ allowed but who softened later when he came to the conclusion that Marx’s uniform theories didn’t in fact fit every nation in the world and that Soviet Russia was in any case the worst of all vehicles for it; a second American, Ralph Richard Keithahn, who went there in 1925 to convert the Hindus to Christianity but ended up being converted – or semi-converted – by them; and Catherine Mary Heilemann, who went to teach and help women and children in the Himalayan foothills and fell foul of the imperial authorities by providing them with food and medicines while their menfolk were staging an illegal strike.

All of them adopted Indian dress and customs, and two of them Hindu names, in obedience to Gandhi’s strict injunction: ‘If the Englishman wishes to remain here as India’s servant, as a brother to the Indians, if he wishes to live here on condition of giving up his imperious

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Under its longest-serving editor, Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair was that rare thing – a New York society magazine that published serious journalism.

@PeterPeteryork looks at what Carter got right.

Peter York - Deluxe Editions

Peter York: Deluxe Editions - When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines by Graydon Carter

literaryreview.co.uk

Henry James returned to America in 1904 with three objectives: to see his brother William, to deliver a series of lectures on Balzac, and to gather material for a pair of books about modern America.

Peter Rose follows James out west.

Peter Rose - The Restless Analyst

Peter Rose: The Restless Analyst - Henry James Comes Home: Rediscovering America in the Gilded Age by Peter Brooks...

literaryreview.co.uk

Vladimir Putin served his apprenticeship in the KGB toward the end of the Cold War, a period during which Western societies were infiltrated by so-called 'illegals'.

Piers Brendon examines how the culture of Soviet spycraft shaped his thinking.

Piers Brendon - Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll

Piers Brendon: Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll - The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West by Shaun Walker

literaryreview.co.uk