Bharat Tandon

His Life as a Novelist

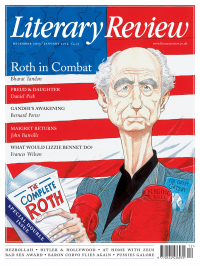

Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books

By Claudia Roth Pierpont

Jonathan Cape 353pp £25

On the surface, it might seem an odd decision for a critic to cleave faithfully to the grain of Philip Roth’s life and works, since so much of both has been defined by conflict, if not downright contrarianism. After all, Roth’s career can be traced as a relief map of oppositions, from the outraged reactions to his 1959 New Yorker story ‘Defender of the Faith’, famously reworked in The Ghost Writer (1979) as Judge Wapter’s ‘TEN QUESTIONS FOR NATHAN ZUCKERMAN’ (‘Can you honestly say that there is anything in your short story that would not warm the heart of a Julius Streicher or a Joseph Goebbels?’), to his ongoing struggles, over the years, with various misconstructions of his work and with that ‘anti-Roth reader’ which he once conjured for Hermione Lee (‘I think, “How he is going to hate this!” That can be just the encouragement I need’). Likewise, given the running concern in Roth’s post-1960s novels with fractured and invented identities and the alternative trajectories of ‘counterlives’, is his not a story that might more naturally be served by a fragmented, non-linear treatment, after the fashion of Jonathan Coe’s exemplary biography of B S Johnson, Like a Fiery Elephant, or at least the kind of metafictional meditation that Roth himself offered in The Facts? In this light, Claudia Roth Pierpont’s defiantly linear Roth Unbound could have come over as damagingly counterintuitive, like writing a biography of Borges in the style of John Forster’s life of Dickens. It is to her credit, then, that much of it offers instead a demonstration of the quieter virtues of her more traditional approach – even if it results in a few significant omissions along the way.

Any biographical study of Roth is always going to have to take on board some tricky (if aesthetically fertile) circumstances. The life of writing and the lives of writers have often been major elements in Roth’s novels, but ones that take on deliberately confusing fictional lives of their own – for instance, Nathan Zuckerman begins life as a fictional creation of Peter Tarnopol in My Life as a Man (1974), only to resurface as an author in his own right in many subsequent novels. Over and above that, though, is the biographical legend of Roth himself, on which his novels both do and don’t draw. A cynical and/or cloth-eared reader of Roth might well take his story as the great template for the modern-author-as-celebrity (though this itself looks increasingly as if it may prove to be a blip in literary history, since writerly celebrity presupposes the existence of people who read). The Newark childhood in the 1930s and 1940s, which animates both Roth’s first book of fiction, Goodbye, Columbus (1959), and his last, Nemesis (2010); the rise to public fame and notoriety following the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint in 1969; the high-profile romances with Claire Bloom: these already feel like parts of the mythology of late-20th-century literary life, perhaps because so much of Roth’s career overlaps with a time when literary novelists were people whose names were known, and whose books were (at least) bought. At the same time, though, Roth’s writing has played a bloody-minded, if aesthetically justified, game around the borderline between life and art: translating what might appear to be recognisable elements of autobiography into the parallel dimensions of imaginative fiction, insisting on the prerogative of fiction to be something other than the simple product of its original ingredients and sources, a synthesis that can’t simply be broken back down into its constituent elements.

Roth Unbound has two particularly strong selling points. It is the first full-length study to be published since Roth’s public announcement that Nemesis would be his final novel. It is therefore the first to cover what currently looks to be his entire oeuvre (presumably this is what the publishers mean when they claim that ‘there has been no major critical work about him, until now’ – for otherwise the likes of Lee, Debra Shostak, Derek Parker Royal and Helen Small would have reason to complain). Secondly, Roth has made himself available as a commentator on – if not wholly a collaborator with – Pierpont’s project, with the result that her account of his life and works is supplemented with marginal illuminations from her subject himself. For example, the memories he offers of the anti-Semitic undercurrents in the Newark of his youth (‘virtually no one in the neighborhood, he remembers, chose to own a Ford’) provide an enlightening gloss on his treatment, in The Plot Against America, of the sheer outrage that the fictional Lindbergh administration perpetrates as it brings a different war literally to Newark’s doorsteps. Pierpont, too, is at her best when she’s not trying to mine the fiction for simple autobiographical correspondences or translations. Her sharpest observations are, rather, on the way the facts of Roth’s history might bear upon those acts of fictional creation that transfigure the mere facts, as witnessed by her account of Roth addressing a seminar: ‘How could he be expected to “identify” with the characters of a Christian writer like Dostoyevsky? How? Through literature itself, he tells them – literature, in which we can identify with anyone and become larger than ourselves.’

While Pierpont’s is obviously a sympathetic account of Roth’s work, it isn’t, fortunately, a sycophantic one – certain novels and phases of the fiction come in for some especially searching criticism, notably the post-Portnoy comedies of the early 1970s. There are some areas, however, in which her approach doesn’t convince quite so much. Her personal and idiomatic familiarity with Roth and his social milieu results in the odd phrase that might be more at home in something like Hello! (‘The spartan cabin is based on Roth’s writing studio, which stands just a couple of hundred feet from his beautiful, spacious house’). More problematically, the imperative to cover the whole oeuvre with something like a fair distribution of attention means that certain points are raised tantalisingly but then not explored as fully as they might be. The example of F Scott Fitzgerald first crops up in Pierpont’s early discussion of Goodbye, Columbus, and his imaginative presence in Roth is something to which she returns when discussing the later Zuckerman sequence. She rightly notes ‘the faint echo … of the end of Gatsby’ in Zuckerman’s description of Coleman Silk in The Human Stain, leaving his family ‘in order to live within a sphere commensurate with his sense of scale’. But Fitzgerald’s footprints are visible repeatedly in these novels – after all, The Human Stain restages a version of Gatz’s funeral just as deliberately as the later Exit Ghost reworks James’s The Aspern Papers – and it would have been fascinating to have heard more on these echoes, not least because they chime with an imaginative concern that has run throughout Roth’s work, from beginning to (apparent) end.

‘The fact remains’, Zuckerman declares in American Pastoral, ‘that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong then, on careful consideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.’ Of course, in Roth’s fiction, it’s never been just about getting people wrong, but also about being got wrong by them in turn: time and again, the novels meditate on the question of whether people are their own Gatsby-esque self-

creations, or merely the creatures of others’ wilful or unwitting misinterpretations. In these explorations, though, Roth has had extensive recourse to one quality that Roth Unbound slightly underplays. Pierpont rightly notes that ‘wild, distracting, and antic are Roth’s ways of avoiding pomposity, sentimentality, and didacticism’ – yet it is the most ‘antic’ novels (Portnoy notwithstanding) about which she has least to say. For sure, novels like Our Gang are one-trick affairs, but it is not as if the late masterpieces simply or cleanly leave them behind; rather, Roth finds new ways to tap their indecorous energies, just as Coleman Silk’s story replays as high tragedy a version of what originally happens as grim farce in Zuckerman Unbound. So by privileging the decorous, Roth Unbound emerges as a valuable contribution to thought about Roth, but one which – dare one say it? – risks making him sound a bit too well behaved. Which is not to say that Pierpont doesn’t offer us any of the other Roth – perhaps the finest moment in the whole book is her vignette of Roth as De Niro, as LaMotta, in Raging Bull:

But he’s still on his feet and he’s now staggering toward me, proudly wheezing out the words – Roth does an excellent De Niro – ‘You never got me down, Ray. You hear me? You see? You never got me down, Ray, you never got me down.’

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

The era of dollar dominance might be coming to an end. But if not the dollar, which currency will be the backbone of the global economic system?

@HowardJDavies weighs up the alternatives.

Howard Davies - Greenbacks Down, First Editions Up

Howard Davies: Greenbacks Down, First Editions Up - Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent...

literaryreview.co.uk

Johannes Gutenberg cut corners at every turn when putting together his bible. How, then, did his creation achieve such renown?

@JosephHone_ investigates.

Joseph Hone - Start the Presses!

Joseph Hone: Start the Presses! - Johannes Gutenberg: A Biography in Books by Eric Marshall White

literaryreview.co.uk

Convinced of her own brilliance, Gertrude Stein wished to be ‘as popular as Gilbert and Sullivan’ and laboured tirelessly to ensure that her celebrity would outlive her.

@sophieolive examines the real Stein.

Sophie Oliver - The Once & Future Genius

Sophie Oliver: The Once & Future Genius - Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife by Francesca Wade

literaryreview.co.uk