Adam Douglas

Signature of the Times

In July 2016 a collection of more than 550 modern first editions sold at auction in Dublin, the largest single sale of such books in Ireland. The reason for the auction’s success was simple. Most of the books had been signed by their authors.

The collector of these first editions, Dr Philip Murray, had hit on the technique of writing to authors to ask for permission to send a copy of one of their own books to sign, enclosing a stamped addressed envelope for them to return it in. His polite approach paid dividends. Over time, he even established friendships with some of these authors, including Seamus Heaney, Gabriel García Márquez and Cormac McCarthy.

One might think that no author communicates with his or her reader more directly and profoundly than through a novel, but a book that is individually signed offers the owner the additional frisson of actual personal contact with its author. The value of an author’s signature only increases with time. In 1616 the poet and playwright Ben Jonson collected his writings into a folio volume, placed his portrait at the front, titled it his Workes (scorning the mockery of those who thought mere plays unworthy of such dignified treatment) and offered the book for sale to the general public. Jonson himself gave copies of this folio to a select few, each with a personal message. The small number of surviving books inscribed by Jonson make him real to us across the centuries.

Later authors tended to eschew such self-promotion. Jane Austen, for one, never signed her own books. Her earliest novels appeared with little fanfare, but the quality of her writing soon caught the eye of John Murray, publisher of Byron and Scott. In 1815 he published Emma, the last novel printed in her lifetime, in the approved Regency manner. This meant choosing a suitable dedicatee. Murray proposed the Prince Regent. Austen despised the corpulent spendthrift but did as she was told; the dedication copy, expensively bound in red morocco, though not personally signed by Austen herself, still resides in the Royal Library at Windsor. Murray set aside another dozen copies for Austen’s use. She did not presume to inscribe any of these herself, even the copy she sent to her literary hero Maria Edgeworth, but they all have ‘From the author’ written in them by one of Murray’s clerks.

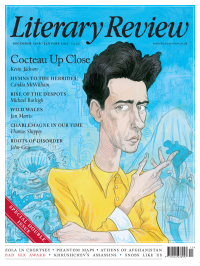

In terms of authorial bravado, Jonson’s spiritual descendant was Charles Dickens, whose earliest works were published under the soubriquet ‘Boz’. Only one week after the publication of Oliver Twist in November 1838, the proud author could keep quiet no longer and ordered the title pages to be reprinted with his real name. By the time of his next novel, Nicholas Nickleby (1839), any remaining shred of reticence had gone. In place of a scene from the book, the usual image that greeted the reader, the engraved frontispiece contains a flattering portrait of the handsome young author, adorned with a reproduction of his signature. And what a signature it is, festooned with an emphatic mass of swirling underlinings – the signature of a showman, actor or circus performer. It was with the same flamboyance that Dickens inscribed his books. He would typically include the name of the recipient, the date in full, the address of the place where the inscription was made and, of course, that fantastical signature.

Signed books became a regular fixture in the Edwardian era. Illustrated Christmas gift books had grown in popularity during the 19th century, but a new chapter in their history opened in 1905, when a limited edition of Washington Irving’s short story ‘Rip Van Winkle’ with illustrations by the artist Arthur Rackham was published. It was expensively dressed in a vellum binding decorated in gilt and was signed not by the author, who was dead, but by the artist. Soon every gift-book illustrator was following suit, inscribing their names in deluxe editions of two hundred or three hundred copies. Artists are, of course, accustomed to signing their names on their paintings.

The exact moment when a real-life author condescended to sit behind a table in a bookshop to sign copies of his or her book is very hard to pin down, but there is no available evidence for the practice before the Second World War. Although the Hogarth Press, for instance, issued signed limited editions, it’s impossible to imagine Virginia Woolf peering out from behind a stack of her own books in a shop, even one as simpatico as the Soho premises of Francis Birrell and David Garnett (Frankie and Bunnie to their Bloomsbury chums).

If they wanted personal contact, most readers would have had to be content with a public lecture. Mark Twain made lecture tours a major part of his schedule, earning a good income from them. He did not read from his books, preferring to lecture on a wide variety of subjects from memory. Nor did he offer official signing sessions. Nevertheless, he was hounded with requests to inscribe his books. When he discovered that tuft hunters were not bothering to keep the books, but cutting out the signatures and selling them separately for as much as $5 each, Twain made it his practice to inscribe books only on the inside front cover, to prevent such behaviour.

The lecture format also took off in Britain. In 1930 the feisty young Christina Foyle began holding her famous Literary Luncheons, but the Foyles customers, up to two thousand of them at a time, would not get their books signed by the likes of George Bernard Shaw or H G Wells – they were there to be lectured at. Even this was considered daringly democratic. Selfridges, which opened in 1909, boasted a ‘signature window’ on which visiting celebrities scratched their autographs, using a diamond-tipped wand. In spite of having a library-like book department, however, the store seems to have delayed holding personal book signings until the egalitarian atmosphere of the era after the Second World War made such a thing socially acceptable. Ian Fleming refused several invitations to signing sessions at both Selfridges and Harrods in the late 1950s, declaring them the haunt of old women, which suggests that their rituals were well established by that date.

The organisers of a modern book signing session have more to worry about than the social sensitivities of the author. Not long after J K Rowling’s publishers released deluxe editions of the first three stories in the Harry Potter series with a gilt facsimile of her signature, copies of her books soon began circulating on auction websites with autographs mimicking those of the special editions. For the official signing sessions of the later Harry Potter books, Bloomsbury issued special stationery, named tickets and a hologram sticker to be placed next to Rowling’s signature. When an author’s signature adds so much value, authentication is everything.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk