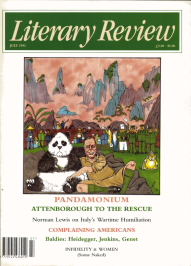

David Attenborough

Are They Really Bears?

The Last Panda

By George Schaller

University of Chicago Press 251pp £19.99

Why choose an aberrant Chinese bear, teetering on the brink of extinction, as a symbol for a conservation charity? Why not pick something less exotic and more universal? Or a creature which is a key element in an important ecosystem? And isn’t it giving an unnecessary hostage to fortune to hitch your image to an animal that might quite soon disappear altogether and so declare your mission a failure?

In the end, the appeal of the animal’s black and white pattern proved irresistible to the group of conservationists who were launching a new international charity, back in 1961. Peter Scott designed a stylization of the animal seen head-on as a badge and the giant panda became the emblem of the World Wildlife Fund for Nature and in the process redesigned Peter Scott’s symbol, much to its detriment).

In 1979, to mark WWF’s approaching 21st birthday, someone suggested that as the Fund claimed to be a worldwide organization, it should do something in China and – belatedly – help to protect the animal it had adopted as its symbol. So one of the West’s most intrepid, expert and experienced field zoologists, George Schaller, was despatched to China to discover what might be done to help the panda. His scientific account of his findings, written in collaboration with three Chinese colleagues, was published back in 1985. That book is full of maps, charts, statistics and all the detailed information you would expect in a modern zoological treatise. This new one, however, is very different. Of course, it contains a great deal about pandas, vivid descriptions of the animals in the wild, extracts from Schaller’s journal as he and his wife Kay trekked through the mountains following their radio-collared quarry, and an examination of the question that seems to obsess many – whether the giant panda is really a bear or a raccoon. But he also writes revealingly and candidly about the people he worked with. Because of what he has to say about that aspect of the enterprise, he delayed the publication of this more informal book, in case it should hinder rather than help the work of panda conservation.

Right from the beginning, he was caught between two grinding bureaucracies – WWF on the one hand and Chinese officialdom on the other. The Chinese, understandably, were sensitive on the issue. The panda, after all, was officially designated a national treasure. Suppose the Americans were suddenly visited by a delegation of Chinese who told them that they, the Chinese, had unilaterally taken America’s national symbol, the bald eagle, as their emblem, and then went on to explain that since the bird was, in their view, shockingly persecuted, they were about to send over their own experts to supervise its protection. I imagine the Americans would react rather stiffly. In any case, the WWF delegation, delivering a similar message to the Chinese, did not behave with outstanding tact. They told the Chinese that they would arrange for the campaign to get worldwide publicity and illustrated the sort of thing they had in mind by producing mock-ups of postage stamps carrying the panda’s image. Unfortunately, the stamps also showed that the country chosen for this notional example was Taiwan.

The Chinese, for their part, wanted to extract as much cash as they could from the deal. They insisted that if the WWF wanted to work in China, it had to pay two million dollars for the building of a research institute. Not only that, but the institute had to be stocked with a great quantity of scientific equipment, including adiabatic bomb spectrophotometers and other such high-tech gadgets, the bulk of which had no relevance whatever to panda research.

While negotiations, misunderstandings and bargainings between officials on both sides meandered on, Schaller managed to get into the mountains of southwest China and started looking for pandas. Here too a fundamental difference of attitude between the two parties became apparent. Schaller is the epitome of the patient, not to say stoical, naturalist observer. He wanted to find out as much as possible about the animals’ habits in the wild. How far did they travel? What were their social relationships? Exactly what did they eat and when? Only when the answers to such questions were known was it possible, in his view, to devise an effective plan for panda conservation. The Chinese had a different approach. They wanted to catch pandas and start breeding them, preferably in a newly built and extravagantly equipped research institute. That these two aims were to some extent eventually reconciled and that the project continued for four and a half years was, in large measure, due to Schaller’s patience and diplomacy.

What is the situation today, fourteen years on? One judges from this book that in spite of all the work and the money, the giant panda is, at best, only marginally better off than it was before the project started. There are still only a thousand or so of the animals in existence. After Schaller’s initial study, there was a widespread die-off of arrow bamboo, the animal’s primary food. Schaller believes that, allowed some freedom of movement and given some protection, the animals could have survived this crisis by themselves. The Chinese used it as a justification for catching more pandas. They trapped 108. Thirty-five were transported to areas where the bamboo was unaffected. But thirty-three others died and forty still remain in captivity with little prospect of them breeding.

Clearly, the WWF’s choice of the giant panda as its symbol was more appropriate than it realised, for this absorbing book makes it only too apparent that if conservation is to succeed worldwide, it is not only the habits and sensitivities of rare animals that have to be studied and understood, but those of the most abundant, the most variable, complex and difficult to manage of all large mammals, the human species.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Under its longest-serving editor, Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair was that rare thing – a New York society magazine that published serious journalism.

@PeterPeteryork looks at what Carter got right.

Peter York - Deluxe Editions

Peter York: Deluxe Editions - When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines by Graydon Carter

literaryreview.co.uk

Henry James returned to America in 1904 with three objectives: to see his brother William, to deliver a series of lectures on Balzac, and to gather material for a pair of books about modern America.

Peter Rose follows James out west.

Peter Rose - The Restless Analyst

Peter Rose: The Restless Analyst - Henry James Comes Home: Rediscovering America in the Gilded Age by Peter Brooks...

literaryreview.co.uk

Vladimir Putin served his apprenticeship in the KGB toward the end of the Cold War, a period during which Western societies were infiltrated by so-called 'illegals'.

Piers Brendon examines how the culture of Soviet spycraft shaped his thinking.

Piers Brendon - Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll

Piers Brendon: Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll - The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West by Shaun Walker

literaryreview.co.uk