D J Taylor

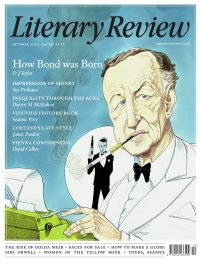

Becoming James Bond

Ian Fleming: The Complete Man

By Nicholas Shakespeare

Harvill Secker 864pp £30

Anthony Powell, two and a half years older than Ian Fleming, remembered him as ‘one of the few persons I have met to announce that he was going to make a lot of money out of writing novels, and actually contrive to do so’. Fleming and his older brother, Peter, turn up in Faces in My Time (1980), the third volume of Powell’s memoirs, in connection with the short-lived 1930s magazine Night and Day, with Peter filing editorial notes and Ian raising money for the magazine in the City. Coming across a bound volume half a century later, Powell was immediately struck by what he called the ‘Fleming impact’. One of the signature marks of Nicholas Shakespeare’s new biography is its terrific sense of clannishness. Rarely has there been a collective unit whose members looked out for, supported, interfered with and privately disparaged each other with such unrelenting tenacity.

Doubtless this fellow feeling was a consequence of the family’s meteoric rise to fame. The Flemings were one of those extraordinary, but far from unusual, mid-Victorian enterprises in which the grandfather makes the money, the second generation establishes the social position and the third pursues a sideways shift into the more exotic quadrants of literature and the arts. Robert Fleming, who grew up in poverty in Dundee, founded the private bank that bore his name. His son Valentine became Tory MP for Henley and died on the Hindenburg Line in 1917, leaving a legend of heroism and disinterested public service so profound that a framed copy of Winston Churchill’s obituary of him in The Times hung permanently on the wall beside Ian’s bed.

Valentine had four sons, of whom Ian, born in 1908, was the second. They eventually acquired a half-sister, a product of their widowed mother Eve’s carry-on with Augustus John. None of this made for an easy childhood, and most of Ian’s early years seem to have been undermined by the paralysing celebrity of his brother Peter; the third brother, Richard, went to work in the family bank, and a fourth, Michael, was killed in the Second World War. Shakespeare offers interesting parallels with the rivalry that existed between Evelyn and Alec Waugh, but whereas the younger Waugh soon left the author of The Loom of Youth’s reputation sprawling in the dust, Ian took nearly three decades to escape from his brother’s shadow. Captain of the Oppidans at Eton and head of Pop (or the Eton Society), the possessor of an Oxford first, tipped as a future editor of The Times, Peter spent the early 1930s writing up his adventures in far-flung parts of the world and, like T T Waring in Powell’s What’s Become of Waring (1939), being compared to ‘everyone who had ever written a successful travel book, Burton, Doughty, Hudson, and the rest of them’.

Ian, meanwhile, scraped by at school, showed early signs of a lifelong interest in the ladies, was thrown out of Sandhurst for contracting a venereal disease and failed to get a job at the Foreign Office. A brief interlude at Reuters gave promise of better things, but by the mid-1930s he was becalmed at Rowe & Pitman – ‘the worst stockbroker in the world’, Peter remembered, with only a single recognised client and a working brief that largely consisted of taking people out to lunch. Already the key elements of the Fleming personality had shifted into view. A ‘playboy puritan’, Shakespeare calls his subject, saturnine and self-absorbed, poised and diffident, womanising and crony-haunted, both focused on his family and oddly detached from it. The key Fleming leisure pursuit turns out to have been slaughtering wild animals; Ian’s happiest times seem to have been spent on the golf course, and at all times he seems to have existed at one remove from the people around him.

All through this early stretch of his career (whose social and cultural scenery Shakespeare handles with aplomb), another subtext is silently declaring itself. That is the tremendous old pals’ act of which upper-class English life in the interwar era consisted. No scapegrace younger son’s prospects are so benighted that they can’t be revived by familial influence; City jobs are bestowed out of respect to exalted grandpapa; no rock on the road to Le Touquet is so sequestered that it doesn’t harbour someone you messed with at Eton. In May 1939 a chum showed a couple of reports Ian had written on the European situation to some highly placed friends. Admiral Godfrey, director of naval intelligence, in search of a PA ‘who had to have contacts in the City, be a bit of a man of the world, get on with people and have imagination’, realised on the instant that he had struck gold.

In a book not short on detail – more of this in a moment – Shakespeare expends vast amounts of ink in trying to work out exactly how adept Commander Fleming, as he soon became, was at his job and how widely his operational net extended. Whatever Fleming’s precise achievements in Room 39 at the Admiralty Office, he clearly found himself at home in a milieu far more suited to his administrative and imaginative talents than any employment previously offered him. He was a resourceful and consistently adept man-manager at the very centre of the British intelligence machine, Shakespeare concludes, often seen at Bletchley Park and ‘a war-winner’, according to his old boss. Encouraged by the press magnate Lord Kemsley – another father figure in the Godfrey mould – he emerged into the post-1945 world as head of the Sunday Times foreign desk and with a long-term mistress, Lord Rothermere’s wife, Ann, who divorced her Daily Mail-owning husband in 1951 and married the usurper the following year.

Once again, the taint that seems to have hung over practically every aspect of Fleming life was soon making its presence felt. Tough-minded – sometimes to the point of callousness – and sociable, Ann was keen to populate the couples’ house in Victoria Square with her intellectual friends. Some of Shakespeare’s funniest passages take in the spectacle of her husband arriving home after a hard day at the office to find, as it might be, Cyril Connolly, Peter Quennell and Stephen Spender enjoying highbrow conversation with his wife. There was also an affair with Hugh Gaitskell, who became leader of the Labour Party in 1955. Forged in a crucible of marital strife and growing ill-health (the result of a seventy-a-day cigarette habit), Fleming’s first novel, Casino Royale (1953), was greeted by his family with typical hauteur. Several relatives professed themselves shocked by the novel’s vulgarity. Peter’s wife, the actress Celia Johnson, counselled friends not to mention it to her husband on the grounds that he ‘minds so dreadfully’.

Why exactly was it that Peter, his own professional star now slightly on the wane, minded so dreadfully about 007? Shakespeare is good on the creation of the Bond books, written at the rate of one a year and, for all their formulaic precision dredged up from somewhere deep within their creator’s psyche, mattering to him in a way that other aspects of his life did not, and affecting their vast readership on wildly differing levels. Bond may be Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond brought up to date but he is also a post-imperial Cold War warrior. Ripe for superannuation, too, as within a decade John le Carré would be redefining the world of counter-espionage to make it seem as mundane and workaday as any other civil service job. There was a moment, several books in, with sales no more than mediocre, when he almost gave up, only for press excitement over Anthony Eden’s post-Suez convalescence at Goldeneye (the Caribbean estate where Fleming wrote the Bond novels), a film deal, the backing of Lord Beaverbrook’s Express and a presidential endorsement to send the sequence whirling into the stratosphere.

Fascinating, well-researched, neatly written and suitably respectful of previous efforts by John Pearson (1966) and Andrew Lycett (1995), Ian Fleming: The Complete Man is at the same time way too long, a pudding so prodigiously over-egged that it will leave most readers fearful of slipping on the discarded shells. A sadistic master at Fleming’s prep school gets pages all to himself. The description of his louche maternal uncles goes on for seven paragraphs before Shakespeare reaches the rather disappointing (in the circumstances) conclusion that ‘Eve ensured that neither Ivor nor Harcourt came anywhere near her children’.

Fleming died at fifty-six, disillusioned by success and claiming that he would have been happy to swap material gain for ‘a healthy heart’. Caspar, his equally mysterious and solitary son, committed suicide at the age of twenty-three. What remains, after Shakespeare’s eight-hundredth page has ground by, is a desperate sense of melancholy and the thought of something, however obscurely, having gone badly wrong in the family unit. Shakespeare prints an odd little vignette from August 1964. Receiving the news by telephone of Ian’s death as he prepared to go out and reduce the grouse population on Rannoch Moor, his brother Richard told those present merely that he had to travel to England. Peter received the news on another Scottish estate 150 miles away. ‘Not wishing to spoil the shooting’, he said nothing at all.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Coleridge was fifty-four lines into ‘Kubla Khan’ before a knock on the door disturbed him. He blamed his unfinished poem on ‘a person on business from Porlock’.

Who was this arch-interrupter? Joanna Kavenna goes looking for the person from Porlock.

Joanna Kavenna - Do Not Disturb

Joanna Kavenna: Do Not Disturb

literaryreview.co.uk

Russia’s recent efforts to destabilise the Baltic states have increased enthusiasm for the EU in these places. With Euroscepticism growing in countries like France and Germany, @owenmatth wonders whether Europe’s salvation will come from its periphery.

Owen Matthews - Sea of Troubles

Owen Matthews: Sea of Troubles - Baltic: The Future of Europe by Oliver Moody

literaryreview.co.uk

Many laptop workers will find Vincenzo Latronico’s PERFECTION sends shivers of uncomfortable recognition down their spine. I wrote about why for @Lit_Review

https://literaryreview.co.uk/hashtag-living