Steve Richards

Brawls & Brexit

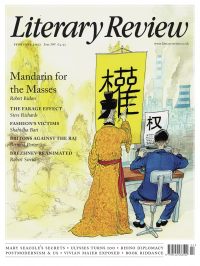

One Party After Another: The Disruptive Life of Nigel Farage

By Michael Crick

Simon & Schuster 592pp £25

Most political figures come and go. Nigel Farage, in contrast, seems always to be around, close to the centre of the political stage. Sometimes he is leading a political party. Occasionally he is setting up a new one. Between such roles he is on television. Currently, the former leader of UKIP and the Brexit Party hosts a nightly show on GB News.

The consequences of Farage’s ubiquity have been seismic, reshaping the UK and the wider political landscape. He sought a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and then a hard Brexit, and ultimately got everything he wanted. The Conservative Party’s embrace of a form of English nationalism was partly a response to the threat that Farage posed. The near-silence of the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, on the subject of Brexit is a form of vindication for him. Starmer knows that Brexit is having calamitous consequences but does not dare to say so. No wonder Michael Crick concludes that ‘it’s hard to think of any other politician in the last 150 years who has had so much impact on British history without being a senior member of one of the major parties at the time’.

Among Crick’s admirable passions is his interest in those individuals or forces that have shaped the major political parties from outside the mainstream. He wrote an important book on Militant, the left-wing group that in the 1980s sought to infiltrate the Labour Party and for a time made life hellish for Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock, the two party leaders during that stormy decade. His biography of Jeffrey Archer, the Conservative MP who became a bestselling author and then a convicted prisoner, was revelatory. Now he has set his sights on Farage, who has never been an MP and yet has been such a prominent figure in recent years.

As Crick always does with his subjects, he has researched meticulously every twist and turn in Farage’s life. He regrets that his investigations were constrained by the pandemic. He need not worry too much. His diligence has enabled him seemingly to have unearthed every internal dispute in UKIP and the Brexit Party, along with the eccentric figures who lined up on different sides in them. The characters that emerge would fit neatly into a Dickens novel. One of the most unsavoury right-wingers to feature in the book is now an avid supporter of the Green Party, lives in Germany and is passionately opposed to Brexit – a novelistic metamorphosis. We are also reintroduced to Farage’s old friend Godfrey Bloom, a UKIP MEP and economics spokesman, who in 2013 famously hit Crick with a party conference brochure as the journalist pursued him down the street after he had made characteristically indiscreet and outrageous remarks in a speech to UKIP members.

This book is full of fights, usually between party members. We see Farage repeatedly falling out with other potential leaders. More prominent members who cannot hide their real views in public have to be admonished. Some flirt with the BNP. Even during the triumphant 2016 referendum campaign, there were two pro-Brexit camps, one led by Farage and the other by Dominic Cummings. Farage and Cummings loathe each other and their campaign groups fought bitterly for pre-eminence. This is the most striking theme of the book. UKIP and the Brexit Party, which Farage set up in 2019 to campaign for a hard Brexit, were utterly dysfunctional most of the time. They make the UK’s main political parties, all going through various existential crises at the moment, seem models of smooth, sophisticated professionalism. The amateurism extended well beyond the eccentric characters near or close to the top. Neither party offered coherent policy programmes beyond opposition to the UK’s membership of the EU.

The incoherence and the contradictory leaps in policy areas did not bother Farage. Crick shows that beyond the question of Europe, Farage had little interest in policy. This indifference almost gave him a protective shield in interviews. When questioned about his party’s previous manifestos, Farage would joke that he had not even read them, let alone written them. The casual approach to policy did not diminish his appeal. Indeed, it perhaps attracted voters who regard politics largely as another form of show business.

From the beginning Farage was drawn to politics as performance. He went to Dulwich College, where he first engaged in robust political debate: his classmates recall him volunteering to speak on any motion, such was his confidence in his powers of persuasion. Crick points out that Farage is an equivocal anti-establishment figure. He was a committed Conservative as a young boy and even today returns regularly to speak at Dulwich, a private school that forms part of a recognisably English establishment, sometimes dressed in the striped old boys’ blazer. After a stint in the City, he went on to become one of the best performers in British politics, making use of platforms such as Question Time, onto which he was regularly invited as UKIP leader, to get his message across. Farage is a far better communicator than Boris Johnson, the other star of the Brexit referendum. He is now a highly effective interviewer on GB News. He has curiosity, unusual in showbiz politicians. What he has never been is a public figure willing to face the consequences of his performances. Like nearly all those who brought about Brexit, he runs a mile when the moment for practical delivery arrives. Farage resigned as UKIP leader the day after the referendum result in 2016. At no point has he been burdened with the hard grind of negotiating a Brexit deal. He opts instead for the much easier environment of the broadcast studio.

Given the chaos of the parties he led and his own distance from the details and implications of Brexit, we need to look elsewhere for the deeper reasons as to why the UK left the EU, especially to the changing nature of the Conservative Party. Margaret Thatcher was pivotal, with her increasingly shrill Euroscepticism. A significant section of the Conservative parliamentary party became more hostile to the EU after the UK fell out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. John Major sought to appease his rebels, but this only deepened their insurrectionary fervour. David Cameron offered a referendum he did not need to hold on the assumption that he would win it. The leadership of Thatcher, the weakness of her successors and the increasing rebelliousness of Conservative MPs go a long way to explaining why Brexit happened.

Farage had a single insight of historical significance. He once told me that UKIP would have the same impact on the Conservative Party as the SDP had on Labour in the 1980s. The threat of another party capturing votes from them would force the Conservatives to change. At key points he was right. Cameron’s decision to call a referendum was partly triggered by fears of defections to UKIP. Johnson’s election as Tory leader and prime minister came about because his party concluded that only he could counter the threat posed by the Brexit Party. But note Crick’s qualification in this illuminating and definitive biography. Farage had the biggest impact of any political figure in modern times ‘outside’ the main parties. It is the big and not so big figures in the Conservative Party that have changed the course of British history.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Russia’s recent efforts to destabilise the Baltic states have increased enthusiasm for the EU in these places. With Euroscepticism growing in countries like France and Germany, @owenmatth wonders whether Europe’s salvation will come from its periphery.

Owen Matthews - Sea of Troubles

Owen Matthews: Sea of Troubles - Baltic: The Future of Europe by Oliver Moody

literaryreview.co.uk

Many laptop workers will find Vincenzo Latronico’s PERFECTION sends shivers of uncomfortable recognition down their spine. I wrote about why for @Lit_Review

https://literaryreview.co.uk/hashtag-living

An insightful review by @DanielB89913888 of In Covid’s Wake (Macedo & Lee, @PrincetonUPress).

Paraphrasing: left-leaning authors critique the Covid response using right-wing arguments. A fascinating read.

via @Lit_Review