Dominic Green

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West

By Mick Brown

Hurst 400pp £25

The British prime minister and the US vice president are the children of immigrants of Indian background: Rishi Sunak is the grandson of Punjabi Hindus who emigrated to East Africa and Kamala Devi Harris’s mother is a Tamil Brahmin. The current and previous British home secretaries, Suella Braverman and Priti Patel, are also of Indian extraction. The candidates for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination include Vivek Ramaswamy, the son of Tamil Brahmins, and Nikki Haley, the daughter of Punjabi Sikhs. No other immigrant group in Britain or the United States has risen so far and so fast.

Meanwhile, India has emerged as the biggest ‘pivot state’ in the US–Chinese rivalry that will shape the coming decades. In 2005, the second Bush administration denied a visa to Narendra Modi, then chief minister of Gujurat, meaning he was unable to enter the United States. The Obama administration welcomed Modi as India’s prime minster in 2014. Since then, both the Trump and Biden administrations have followed suit. In June, when Modi visited the White House, Biden talked of a ‘shared future’ that included collaboration on cancer treatments, space flight, clean energy, quantum computing, semiconductor supply chains and military exercises.

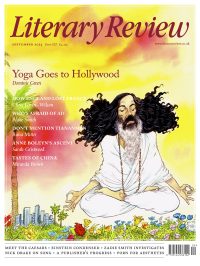

While Modi was in America, he marked International Yoga Day by leading a yoga class at the UN headquarters. This attracted little comment in American media. Everyone does yoga in America. Yoga is now as American as fajitas, and about as authentic. Modi doing the downward dog didn’t fit the emerging narrative, either. You still see Gandhi stickers on Subaru bumpers in college towns and jars of Patak’s rogan josh sauce turn up all over the place, but in New York and Washington, DC, India now means the hard stuff: politics, weaponry, finance, tech and a 1.4-billion-person bulwark against China.

Not so long ago, India’s greatest export to the West, people aside, was spirituality. Mick Brown’s The Nirvana Express is an engaging history of India’s spiritual influence on the West between 1893, when Swami Vivekananda was the surprise star at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, and 1990, when the multimillionaire cult leader and tax dodger Bhagwan Rajneesh popped his sandals. The economic reforms that began the transformation of India’s economy started a year after Rajneesh’s death. The subsequent changes make the history described in Nirvana Express feel almost ancient.

I should mention that my most recent book, The Religious Revolution, feels even more ancient, because it is the Victorian prequel to The Nirvana Express. Brown has written the kind of book that I would write, should my publisher ever speak to me again. Brown, whose previous books include The Spiritual Tourist: A Personal Odyssey Through the Outer Reaches of Belief, has synthesised a small Himalaya of material into a clear and well-told narrative. His subject is not so much India as the uses and abuses of subcontinental religions in the West in the 20th century.

That century proved that Nietzsche had been half-right. Reports of the ‘death of God’ were exaggerated: those who fell out of love with the Christian deity would, it seemed, fall for anything, providing it was exotic and antagonistic to the inherited order. (The first to use Indian religion as a hammer against Christian clericalism was, I think, Voltaire, in the 1760s.) By the end of the 19th century, Western interest in Indian religion had broadened from philosophical speculation (Schlegel and Hegel) and managerial investigation (the East India Company wanting to know what its subjects thought) to the academic study of comparative religion (Max Müller) and the torrent of self-help pseudo-mythology that is still branded as ‘New Age’.

The first products of the New Age reached the mass market in the 1870s with the Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky and Edwin Arnold’s biography of Buddha in verse, The Light of Asia. By the 1890s, Vivekananda was teaching America’s first yoga classes to the bluestockings of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Bava Lachman Dass was exhibiting yoga to crowds at Westminster Aquarium. Vivekananda was a Hindu nationalist, and in Western countries, the rhetoric of Indian religion fused anti-imperialism with liberationism. Edward Carpenter invoked Buddhism in his defence of homosexuality and Annie Besant exchanged Shavian socialism first for Theosophy and then for leadership of the Indian National Congress.

Besant and Charles Leadbeater, a boys’ school headmaster whose hobbies included occultism and masturbation, groomed Jiddu Krishnamurti from childhood as the Theosophical messiah. In 1911, they launched the fifteen-year-old Krishnamurti in London as the answer to the spiritual crisis of what we now call the ‘post-Christian’ West. He was taken up by the rich, educated, sexually frustrated and religiously hungry Lady Emily Lutyens. Her husband, the architect Edwin, was distracted by building New Delhi. He loathed Theosophy (‘priestcraft, popery and hypocrisy’) and was not amused by what he called ‘the sly slime of the Eastern mind’. He was even less amused when his wife’s wacky spiritual hobby bloomed into a passion for the Indian youth whom the papers were calling ‘a chocolate-coloured Jesus’.

Like Oswald Spengler, Krishnamurti was a little ahead of schedule, but perfectly placed for the postwar mood. If you had witnessed the First World War and the chaos of the 1920s, you too might have concluded that you were living in what the Hindus called the Kali Yuga, an age of darkness and misery, and that it was necessary to expedite the world’s transition into the redemptive state that would begin the next yuga.

Membership of the Theosophical Society peaked in 1928 at 45,000. The figure of the guru was ‘now sufficiently embedded in the British consciousness to be taken for a figure of fun’, Brown states. In E F Benson’s Queen Lucia (1920), the ‘Brahmin of Benares’ is exposed as a cook from an Indian restaurant. Krishnamurti, like the Sixties’ archetype he eventually became, went solo after an American tour and had a nervous breakdown in California.

Two graduates of the secret occultist society the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Allan Bennett and Aleister Crowley, headed east to the source of inspiration. Bennett was a Buddhist magician who used ‘a long glass prism with a neck and pointed knob’ as a magic wand. When a Theosophist doubted the powers of his ‘blasting rod’, he paralysed the sceptic for fourteen hours. Crowley was tediously awful, like all addicts, and preferred the ‘egocentric psychology’ of Hinduism to Buddhist inaction, which, he wrote, ‘got on my nerves’.

In 1932, another Indian spiritual figure, Meher Baba, went to Hollywood. Baba was the real thing, which is to say a talented impostor preaching universal compassion, like all the other people in Hollywood. His core message, later pilfered by Bobby McFerrin for a lyric, was ‘Don’t worry, be happy.’ ‘Sex for me does not exist,’ Baba said, though he did enjoy playing cricket. While loitering in Hollywood with ‘the principal purpose of hastening the film project about his life’, he made spiritual approaches to Tallulah Bankhead, the novelist Mercedes de Acosta and Greta Garbo. After eventually growing disenchanted with him, Mercedes de Acosta transferred her affections and allegiance to Sri Ramana Maharshi, who also preached happiness and universal compassion but preferred silent

contemplation to cricket.

Brown might have pondered the use, then and now, that Western fascists and race theorists have made of Eastern theologies. There is, though, more than one path through the material; to cover it all would require a Nietzschean Pneumatische Erklärung, a comprehensive ‘spiritual explanation’ of modernity. Brown, an accomplished music journalist, orients his account towards the 1960s. Addled by postwar comfort and the commodification of drugs, a generation took the likes of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the inventor of transcendental meditation, seriously.

The principle of mutual exploitation had already been established by the time the Maharishi came on the scene. Krishnamurti had primed himself to address the West’s spiritual crisis in its own terms through his reading of Nietzsche and Dostoevsky. The Maharishi could hardly complain when Californian refugees from Nazism cooked up the Human Potential Movement; he too had ‘read extensively in the literature of twentieth-century psychology and psychiatry’. The Maharishi supposedly told the Beach Boys that if they meditated, they would become ‘the most influential group in the world’. He promised the American Broadcasting Corporation that The Beatles would appear in a TV special. ‘He’s not a modern man,’ George Harrison explained to his bandmates. ‘He just doesn’t understand these things.’ The Maharishi understood the modern world better than George did. That was why he ‘always seemed to have an accountant at his side’. God is in the details, especially when it comes to the business of religion.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk