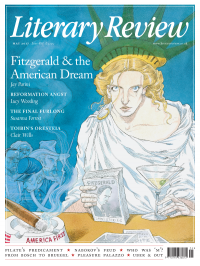

Susanna Forrest

Hanging Up Our Spurs

Farewell to the Horse: The Final Century of Our Relationship

By Ulrich Raulff (Translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp)

Allen Lane 464pp £25

The horse on the cover of Ulrich Raulff’s impressive new book is soaring, bridleless, riderless and all but headless. It has the fuzziness of distance but also the heft and hairiness of life; it is both figurative and real. In tracing our extended exit from the long 19th century, when horses powered nations and shaped the way we thought, Farewell to the Horse attempts to ride both these steeds. Equus caballus is, Raulff explains, a ‘living metaphor’ that can ‘carry not only humans and other loads, but also abstract signs and symbols’ and has ‘more meanings than bones’. When we unharnessed the horse from our omnibuses and ploughs and replaced it with trains and tractors, we lost not just horse power but one of the life forces of Western thought as well.

This unusual book is a series of airy, winging essays that alight briefly on world history, art, literary criticism and historiography before leaping on to make new, often surprising connections. Raulff’s animal is the source of ‘every single great idea that fuelled the driving force of the nineteenth century – freedom, human greatness, compassion, but also the sub-currents of history uncovered by contemporaries such as the libido, the unconscious and the uncanny’. This is not the Pony Club Manual or a trot through the more familiar sights of equestrian art history; it’s Kafka, Aby Warburg, Tolstoy, psychoanalytic theory, Nietzsche and bleak monochrome photos in the style of Sebald. This epic enterprise is relieved by Raulff’s spare, vivid style and deep learning. He is as comfortable analysing the etymology of Pferd and Ross as he is discussing the Chicago School, Clint Eastwood and the Amazons, and he rarely loses his audience.

The first of four parts, ‘The Centaurian Pact, or Energy’, comes the closest to a conventional history of the horse. It includes not just remarkable statistics relating to horses – in 1900 there were 145,000 horses in the French army and 130,000 horses working in Manhattan, while at the same time in Australia there was one horse to every two humans – but also sections on the scents and sounds of that world and explorations of subjects as obscure and essential as the role of oats in the landscape. The second part, ‘A Phantom of the Library, or Knowledge’, loops through the development of equine studbooks and the parallel emergence of human equivalents, such as the Almanach de Gotha, pausing to consider the author’s godfather, who adored fine horses and, under the Nazis, became a member of a mounted SA division. Next comes ‘The Living Metaphor, or Pathos’, which spans the symbolism of the leader on horseback, horses as harbingers of death, bestiality and the chevaux fatals that haunt the great European novels of adultery. In the last part, ‘The Forgotten Player, or Histories’, Raulff explores the way horses have shaped the writing of history itself.

Each part is subdivided into enigmatically titled chapters (‘The Shock’ on cavalry; ‘Teeth and Time’ on grand historical theories) that fragment further into essays just a few thousand words long. Readers accustomed to the lyrical pastoral details of British nature writing, with its well-digested big ideas, will at first glance find it dry and, well, unhorsey. A rather more continental intellectualism, unembarrassed by theory, is on display here – think Michel Pastoureau’s The Bear: History of a Fallen King rather than Charles Foster’s Being a Beast. However, there are also some astonishing stories and personal anecdotes that linger. Raulff’s daring vaults and associations prove exhilarating. A Percheron in Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair recalls the wild barb restrained by a groom in Théodore Géricault’s The Race of the Riderless Horses, which in turn evokes the Parthenon’s steeds. In a chapter called ‘The Jewish Horsewoman’, Raulff begins with the painter R B Kitaj’s The Jewish Rider (1985), which depicts the art historian Michael Podro seated sidesaddle inside a train moving through a landscape that suggests the Holocaust. Raulff explores this painting’s debt to Rembrandt’s The Polish Rider before moving on to an examination of anti-Semitic literary traditions, from the Cossack novelist Pyotr Nikolayevich Krasnov to Gogol, in which the Jew cannot ride and is himself a non-human animal. From there, we whizz on to police horses facing off against ultra-Orthodox Jews in 21st-century Jerusalem, Isaac Babel riding with Red Army Cossacks in the Russian Civil War and a real Jewish horsewoman who almost certainly did not ride sidesaddle: Manya Wilbuschewitz, Russian communist, kibbutz pioneer and mounted patrolwoman in the hills of Galilee in the early 20th century.

War shapes the book and gives its most distressing passages lasting force. It is impossible to forget the historian Reinhart Koselleck’s recollection of seeing a horse, its head half destroyed, galloping madly through columns of marching German soldiers on the Eastern Front in 1942. Koselleck, who served in the Wehrmacht and coined the historiographical terms ‘the age of the horse’ and ‘saddle period’, is the book’s presiding spirit, more so than Equus caballus itself, which appears, suffers and labours, but otherwise has little physical presence.

Inevitably in a book of such complexity, there are slips and anticlimaxes. Some of Raulff’s trapeze feats end in a simple two-handed catch rather than a triple somersault. Several figures, such as the US frontier artist Frederic Remington, appear, are commented on and are then formally introduced a few pages later as though they haven’t yet been mentioned. The Arabian mare in Theodor Storm’s Der Schimmelreiter changes sex mid-paragraph. This is also largely an account of man and the horse rather than mankind and the horse – few women appear or speak directly. And it’s worth noting that we have not yet bid adieu to Equus caballus – 60 per cent of horses living today are beasts of burden in the developing world. Furthermore, Raulff’s conclusion that we need a new, non-anthropocentric history is odd, given that new academic disciplines like anthrozoology and animal-centred history are already flourishing.

But Farewell to the Horse covers ground as rapidly and thrillingly as a Cossack horseman. It lays bare a dizzying network of connections and repeatedly offers unfamiliar approaches to old themes. Raulff ends with a tale from his childhood in Westphalia in the 1960s of a farm horse that was bitten by an adder. The horse lingered on for four weeks, ‘poisoned to the very tips of his golden mane’, before the swelling in his chest burst and ‘out poured a gush of dark pus’. Stunned but cured, the horse was led out into the light, to find, as Raulff records, that ‘he had survived’.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk