Jan Morris

Kidnapped

Abducting a General: The Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete

By Patrick Leigh Fermor

John Murray 206pp £20

In death as in life, Sir Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor, DSO, etc, etc, marches epically on.

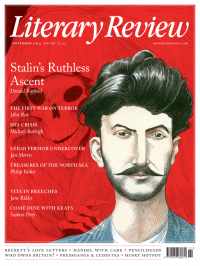

Paddy (as he is known to nearly one and all) left us three years ago, but since then he has been commemorated by majestic obituaries everywhere, a magnificent biography, a reconstructed final volume of his own masterpiece of travel writing, an eager book of travel that follows in his footsteps and a website largely dedicated to his memory. Now we have a book that specifically commemorates him not as an adolescent adventurer, or as a scholar-linguist, or as a gypsy-wanderer, or as a legendary hero, or even as the wonderful writer that he ultimately became, but as a soldier. Not so much as a regimental soldier – he would surely have been a curse to stickler adjutants – but as a born guerrilla, in a military métier that the British enthusiastically adopted in the Second World War.

When they found themselves outgunned, outnumbered and often outfought in that conflict, they threw, with Churchill’s keen support, many talents into the unconventional ranks of the Special Operation Executive, formed particularly to wage war behind the enemy lines. It was this cloudy outfit that in 1942 sent Captain Leigh Fermor as an undercover operative into German-occupied Crete. There his command of the Greek language and his easy camaraderie made him pre-eminent among the varied opposition fighters, Cretan and British, who were making a nuisance of themselves on the island; and so there came about his celebrated coup de théâtre, the kidnapping in 1944 of General Heinrich Kreipe, recently appointed to command the German air landing division on Festung Kreta (Fortress Crete).

Much of Abducting a General is not about the abduction but about Leigh Fermor’s activities in Crete during the previous months, recorded here in nine official reports sent by boat or radio to his SOE minders in Cairo. These throw an almost poignant light upon the operation itself, because they show how intimate and heartfelt was his association with the Cretan people.

The condition of Crete under German occupation seems to have been almost fictionally improbable. The occupation was absolute, with German soldiers everywhere, but the underground opposition was ubiquitous too. It had its own networks and strongholds, not only in the wild highlands, but actually within the towns and cities as well, and Paddy’s vividly idiomatic reports irresistibly take us into the skulduggery and derring-do of its secret war. For instance, we meet the friendly shepherd-brigand Manoli Bandouvas, code-named BO-PEEP, and arrange an airdrop of weapons to him in his mountain lair. We narrowly escape discovery when seven Germans arrive at the Monastery of the Twelve Apostles: the abbot hides us in the cellar while he entertains them two feet above our heads, and we watch through chinks in the floorboards. We ride boldly on our bike into the heart of Heraklion, the capital of Crete (codenamed BABYLON), to plot an act of sabotage in its harbour. We order the ‘immediate liquidation’ of a quisling, and he is carted off and shot in a cave (‘Good riddance’). We are surprised at our cliff-top headquarters by three truckloads of German soldiers and escape only by a mad dash down the mountainside. We paste seditious posters all over the place, we ask Cairo for a supply of suicide pills, just in case, and we celebrate our successes and our escapes with merry festivities in inaccessible caverns with irrepressible Cretans.

For always we are in the company of brave, loyal and resourceful Cretan patriots, upon whom all too often our life depends, and it is one of these friendships that gives Leigh Fermor’s generally vivacious reportage a sudden shock of personal tragedy. ‘I have got to record something tragic and horrible’, he writes in his third report. ‘On the evening of 25th of May I accidentally shot SANCHO, and he died shortly afterwards.’ SANCHO was the code name of Yanni Tsangarakis, one of Paddy’s closest friends and comrades. Although the accident was a perfectly forgivable mistake, it seems to have bound him ever more closely to the Cretan cause, and perhaps tempered his responses when he kidnapped Kreipe.

The story of the abduction is well known enough because in 1950 his second-in-command of the operation, Billy Moss, published a bestselling book about it, Ill Met by Moonlight. This was turned into a film by Powell and Pressburger in 1957 starring Dirk Bogarde as Paddy. Leigh Fermor himself told the story again in 1966 for the mass-market weekly Purnell’s History of the Second World War. The magazine, though, cut his text from the thirty thousand words he submitted to the five thousand words required, so that the version of it in this book is the first appearance in print of Paddy’s complete account of the adventure.

It is a wonderful story, of course, which hardly needs telling again, and perhaps for today’s readers, seventy years on, the most interesting thing about it is its constant emphasis on both the vital part the Cretan guerrillas played in the operation and the fact that the Cretan population at large were in no way responsible. Kreipe’s car was left behind when they whisked him off the island to Egypt, and in it a letter was left explaining that the general had been captured by a British raiding force, adding, perhaps a little mendaciously, that no Cretans had helped. This was because General Müller, Kreipe’s predecessor, had been notorious for his savage reprisals upon the population. In the event, it turned out that his successor, too, took violent revenge upon the Cretans for Leigh Fermor’s success – three months after Kreipe’s capture the Germans killed more than 450 Cretan villagers in a series of reprisals for sedition in general and the abduction in particular.

Paddy’s knowledge of this dreadful aftereffect, together with the memory of SANCHO’s death, gives sadness to this book. The Oxford historian Roderick Bailey sums it all up generously and sensitively in a foreword to the tale, while also suggesting that the whole brilliant adventure (called by Kreipe himself a ‘hussar stunt’) was militarily valueless. There is a symbolism of sorts to the ‘Guide to the Abduction Route’, by Chris and Peter White, which acts as an appendix to the volume.

Buses, we are told there, are ‘a good way to get to the start and finish’ of the routes, and perhaps this gentle advice provides a proper coda to Paddy’s tumultuous symphony of life. At heart he was a gentle hero, after all. Let him now rest in peace.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Though Jean-Michel Basquiat was a sensation in his lifetime, it was thirty years after his death that one of his pieces fetched a record price of $110.5 million.

Stephen Smith explores the artist's starry afterlife.

Stephen Smith - Paint Fast, Die Young

Stephen Smith: Paint Fast, Die Young - Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon by Doug Woodham

literaryreview.co.uk

15th-century news transmission was a slow business, reliant on horses and ships. As the centuries passed, though, mass newspapers and faster transport sped things up.

John Adamson examines how this evolution changed Europe.

John Adamson - Hold the Front Page

John Adamson: Hold the Front Page - The Great Exchange: Making the News in Early Modern Europe by Joad Raymond Wren

literaryreview.co.uk

"Every page of "Killing the Dead" bursts with fresh insights and deliciously gory details. And, like all the best vampires, it’ll come back to haunt you long after you think you’re done."

✍️My review of John Blair's new book for @Lit_Review

Alexander Lee - Dead Men Walking

Alexander Lee: Dead Men Walking - Killing the Dead: Vampire Epidemics from Mesopotamia to the New World by John Blair

literaryreview.co.uk