Anne Perkins

Machiavelli in a Gannex

Harold Wilson: The Winner

By Nick Thomas-Symonds

Weidenfeld & Nicolson 532pp £25

When Harold Wilson resigned as prime minister, his longtime friend and ally Barbara Castle wrote in her diary, ‘What exactly was Harold up to? More than had met the eye, I have no doubt.’ No one ever thought that Wilson played things straight.

When he stood down on 16 March 1976, the upwardly mobile Yorkshire lad was the 20th century’s longest-serving prime minister. His resignation came at a time of his own choosing. He had won four general elections, despite coming to power just as the postwar settlement was beginning to collapse, nationally and internationally. As with the Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin, who also resigned to respectful applause, it was only after Wilson left power that the critics really got to work. And, as with Baldwin, no one has yet managed to retrieve his reputation.

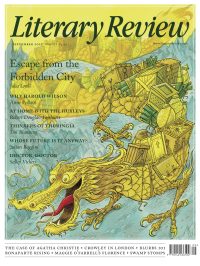

Nick Thomas-Symonds’s new biography, Harold Wilson: The Winner, is a valiant attempt at presenting its subject, if not as a model for our times, then at least as a Labour hero. Members of the Shadow Cabinet, to which Thomas-Symonds in his day job belongs, rarely write biographies purely out of academic interest. His avowed intent is to persuade us to think of Wilson not just as a sharp politician in a Gannex raincoat, but also as a leader who shaped 20th-century Britain. In so doing he seeks to make a virtue of the many manoeuvres by which Wilson kept his party together and in power.

Can we imagine such a thing as an age of Wilson? Surely the final quarter of the 20th century belongs to Labour’s nemesis, Margaret Thatcher? Thomas-Symonds, however, would like us to see Wilson’s Britain as a different place to Thatcher’s: a modern country, socially liberal, anti-racist and in Europe. He sets out, in short, the credit side of the Wilson balance sheet.

No one disputes that the Wilson governments did some great things. The trouble is that they are overshadowed by the less admirable. This is the man who first said that a week is a long time in politics. Thomas-Symonds, who has had access to material that no other biographer has seen, has found little new evidence to explain away his reputation as a tactician, not a strategist.

From university days, Wilson aroused suspicion. Top marks in his finals? He found out what the dons marking the papers wanted and gave it to them. This was Wilson’s first problem: he wanted to succeed just a bit too obviously.

And succeed he did. By 1945 he was an MP and by 1947 a Cabinet minister. But already colleagues were looking at him warily. In 1949, he joined two other young Labour ministers, Hugh Gaitskell and Douglas Jay, in advising prime minister Clement Attlee on the matter of if and when to devalue sterling. They claimed that Wilson seemed able to face three ways at once. He insisted he had always believed devaluation to be unavoidable. Perhaps he just didn’t say so.

Soon his enemies (and his friends) had other grievances. By the late 1940s, Attlee’s government was struggling and exhausted. The 1950 election reduced its majority to five. The young guns were tooling up to fight over the party’s future. In the bitter battle between Gaitskell’s centre-left pragmatists and the missionary socialists led by the father of the NHS, Aneurin Bevan, Wilson chose the side of Bevan. In April 1951 he joined Bevan in resigning, a move that astonished his Cabinet colleagues and hastened the end of Attlee’s government. When, three years later, Bevan – a serial resigner – walked out of the Shadow Cabinet over the creation of a NATO equivalent in southeast Asia, Wilson, who had initially sided with Bevan, broke with him and took his place.

Pragmatist or traitor? Party politics is often a squalid business and, as Thomas-Symonds says in one of his episodic attempts to put his central character in a kinder light, no amount of hindsight can help one disentangle advantage-seeking from expediency and the laudable desire for party unity. Yet while it’s hard not to detect snobbery among the party-loving, public-school Gaitskellites towards this lower-middle-class, pipe-smoking northerner who cherished his family, holidayed in the Scilly Isles and liked going to the football, none of his contemporaries, whether on the left or the right of the party, quite trusted him.

When Gaitskell succeeded Attlee as party leader in 1955, the party’s agonising and politically costly divisions appeared to have been settled in favour of the right wing. Wilson concentrated on quietly accruing power within the party, identifying with the left but never totally severing links with the right. This decade saw Wilson at his most attractive. Bevan might have once said of him, ‘All bloody facts. No bloody vision’, but slowly and effectively Wilson began putting forward a prospectus for a modern Britain that avoided old arguments of left and right and was based on planned economic management, a harnessing of new technologies and a cradle-to-grave education system that excluded no one.

When Bevan and then Gaitskell died prematurely, Wilson was the unchallenged leadership candidate of the left in a party still dominated by the right. Conveniently, however, the right’s leading candidate was George Brown, an erratic and, it proved, unelectable trade unionist. In 1963, aged forty-six, Wilson became party leader.

Wilson assiduously courted his old foes on the right. ‘You must understand,’ he told his old Bevanite friends, ‘I am running a Bolshevik revolution with a Tsarist shadow cabinet.’ But – a fact that Thomas-Symonds does not disguise – the reputation for untrustworthiness that Wilson had acquired on his way to the top meant that friends and critics alike examined his every action for evidence of duplicity. Distrusted by his closest associates, Wilson himself became deeply distrustful of them.

Nevertheless, the Labour Party won a slender majority at the 1964 election and Wilson became prime minister. He was immediately faced with the decision of whether to devalue the pound. Hindsight says he should have done so, but he was fearful of the consequences for a party whose reputation was already scarred by two previous devaluations, in 1931 and 1949. Yet the need to support the pound displaced all serious attempts to restructure the economy, while the rate of inflation quickened and strikes undermined efforts to slow the rate of pay increases. In November 1967, the pound was devalued anyway. In a notorious broadcast, Wilson appeared to suggest this made no difference to the ‘pound in your pocket’.

The enduring social reforms that distinguished Wilson’s first government came largely through the efforts of his home secretary Roy Jenkins. These included the abolition of capital punishment and corporal punishment in prisons, the enshrining of the right to abortion, the legalisation of homosexual acts and the ending of censorship (though not before Wilson had personally censored parts of a play based on Private Eye’s satirical version of the diaries of his wife, Mary). There was also anti-discrimination and equal-pay legislation. These things transformed life in Britain, but with few was Wilson closely associated.

Meanwhile, in Parliament and beyond, the Labour Party was once again pulling itself apart. Unwisely, Wilson sought a political victory over the Tories by legislating to stop unofficial strikes. The threat of ending the right to free collective bargaining brought trade unionists in Parliament and beyond together in a devastating alliance against Wilson and his ally Barbara Castle that nearly propelled Jim Callaghan into the leadership prematurely. Outside Parliament, trade unions and constituency parties, the twin pillars of the Labour movement, moved leftwards in search of radical alternatives to austerity and pay restraint. Internally divided, the party lost the 1970 election.

For many on the right of the party, membership of the EEC became a cause to rally around. Edward Heath’s Conservative government successfully negotiated entry, but with the Tories split on the issue, the necessary legislation could only pass with Labour support. Since Wilson had applied for entry on similar terms in 1967, his decision now to oppose it on the grounds that defeating the Tories was ‘the primary purpose of opposition’ caused outrage. Thomas-Symonds’s defence of Wilson’s actions rests on the argument that he needed to maintain party unity. Labour’s official, conference-approved policy was to put the terms of entry to the public at a general election. Until then, Labour MPs were to vote against membership. Nevertheless, Jenkins, then deputy leader, and nearly seventy other Labour MPs defied a three-line whip to help the Tories get the legislation through the Commons.

In spite of this, Thomas-Symonds argues, Wilson worked to prevent Labour becoming an explicitly anti-Europe party, leaving the way open for a referendum on EEC membership. This was eventually held in 1975, a year after Wilson had returned to Downing Street after defeating the Tories, and confirmed Britain’s EEC membership. It is a sort of defence. But like so many of Wilson’s ploys, it only worked for a bit. Jenkins had by then given up on the Labour Party and the foundations of the Social Democratic Party had been laid. Wilson may have papered over the cracks, but he never reconciled the different wings of the party.

There is always a contemporary dimension to any biography. Harold Wilson: The Winner is at least partly intended to remind today’s Labour movement of the virtues of subordinating differences to the cause of winning power. ‘The sine qua non of a successful leader is to win elections,’ observes Thomas-Symonds. But, as Wilson’s career shows, winning power cannot be the sole objective. Political parties also need to agree on what power is for. Wilson’s Labour Party rarely agreed on anything. It was only his capacity for political sleight of hand that sometimes made it seem as though it did. Thomas-Symonds, a lawyer by training, is a good and careful advocate. But Wilson’s political trickery is too well-documented to be forgotten.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk