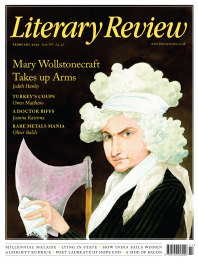

Judith Hawley

Mary, Quite Contrary

Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics

By Sylvana Tomaselli

Princeton University Press 231pp £25

While Mary Wollstonecraft earned her place at the table for pioneering women in Judy Chicago’s art installation The Dinner Party (1974–9), she would not be everyone’s ideal guest. She has a reputation as an acerbic killjoy. She deemed novels to be the ‘spawn of idleness’. She did not embrace women in sisterhood but censured them for their propensity to ‘despise the freedom which they have not sufficient virtue to struggle to attain’. Wollstonecraft has proved both an inspiration and a challenge to those who have come after her.

Her life and works, as Sylvana Tomaselli demonstrates in this wide-ranging new book, contain startling contradictions. On the one hand, she championed women’s capacity for reason in an age that largely treated them as sentimental playthings and decorative accessories for men. On the other, she fell passionately in love with the dashing and unscrupulous American businessman Gilbert Imlay. So fixated on him was she that she undertook a perilous journey to Scandinavia in an attempt to please him and then twice attempted suicide when he dumped her and their illegitimate daughter. In a similarly contrary manner, she proposed a ménage à trois with the Romantic painter Henry Fuseli and his wife, and later wed the radical philosopher William Godwin, though both of them were opposed to marriage. In some ways it is fitting, then, that Maggie Hambling’s much-derided statue in her honour at Newington Green in north London, where Wollstonecraft established a school for girls, gives off such mixed messages of awkward eroticism and shiny, hard magnificence. Wollstonecraft both flouted social norms and lived in defiance of some of her own public statements.

Tomaselli’s Wollstonecraft sets out to make sense of the apparent contradictions between her life and her philosophy, as well as within her thought. It is a much more appropriate monument to Wollstonecraft and her legacy than Hambling’s infuriating statue. Tomaselli’s subtitle, ‘Philosophy, Passion, and Politics’, indicates that she finds a mutually illuminating relationship between Wollstonecraft’s thinking and feeling and the revolutions and upheavals through which she lived. I should point out that this is not a biography of Wollstonecraft: it does not narrate in detail her extraordinary life, from her birth in 1759 to her ghastly death at the age of thirty-eight after giving birth to a daughter, Mary, the future author of Frankenstein and wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley. A historian of political philosophy, Tomaselli isolates important intellectual relationships and sketches broad patterns in Wollstonecraft’s career as a passionate philosopher. Less space is given to her relationship with Godwin than it deserves. Godwin was more of a match for her intellectually and morally than Imlay. It would be good to know what they learned from each other.

Wollstonecraft reveals the links between passion and politics in the preface to her unfinished autobiographical novel, The Wrongs of Woman; or, Maria. She highlights ‘the misery and oppression, peculiar to women, that arise out of the partial laws and customs and society’. And it is this link that underlies Wollstonecraft’s criticisms of women in her most famous work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). There, she repeatedly calls women weak, foolish, sensual and tyrannical and upbraids them for being bad mothers and obsessed with appearances. Yet rather than instantiating the patronising and misogynistic views of Rousseau and other male commentators on women, she has a two-fold aim: to expose the evils inherent in the contemporary ideal of polite femininity and to reveal the source. Women are weak, she says, because laws and customs make them so. She deduces ‘from the present conduct of the sex, from the prevalent fondness for pleasure, which takes place of ambition and those nobler passions that open and enlarge the soul’ that ‘the instruction which women have received has only tended, with the constitution of civil society, to render them insignificant objects of desire; mere propagators of fools!’ Women are educated to be inferior in order to perpetuate a system of inequality. Inequality between the sexes supports the unequal distribution of wealth and the ‘preposterous distinctions of rank, which render civilization a curse, by dividing the world between voluptuous tyrants, and cunning envious dependents’.

Women, according to Wollstonecraft, are trained up to be sexual beings: ‘they are made slaves to their persons, and must render them alluring, that man may lend them his reason to guide their tottering steps aright.’ To use a phrase deployed by second-wave feminists in the 1960s, the personal is the political. And, in her ad hominem attacks on Edmund Burke in her vindictive A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), the political is personal. Tomaselli says that when Wollstonecraft argues against Burke and Rousseau in each Vindication, she deploys reason ‘as a battle axe against her opponents’. Cutting them down, she demonstrates her superior rationality and renders them ‘unmanly’.

Despite their titles, these two works are not, as Tomaselli argues, really about rights, and Wollstonecraft did not set out a charter of demands for legal changes (she intended to add a second volume to The Rights of Woman in which she would examine ‘the laws relative to women’ but did not produce it). Tomaselli adds that the points made in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman ‘cannot be said to be systematic’. Nonetheless, she seeks to find coherence and consistency across the range of Wollstonecraft’s works, including her novels, travel writing, educational tracts, treatise on the French Revolution and extensive literary journalism. (Wollstonecraft was rescued from being a governess – the common fate of the distressed gentlewoman – by the radical publisher Joseph Johnson, who enabled her to make a living as a highbrow hack.) According to Tomaselli, ‘Wollstonecraft’s belief in the unity of humanity is the stepping-stone to understanding her social and political views.’ What she means by this is that people ‘across time or diverse parts of the world, all shared the same God-given nature’.

What follows from this? Any apparent inequality is the result of historical or social circumstances – nurture, not nature, if you like. If, for example, women or Africans are seen as inferior, that is because society has made them so. Society can make them better. Wollstonecraft, like many of her radical contemporaries, believed in human perfectibility. She continued to place her hopes in the French Revolution, writing in 1794 that she was ‘confident of being able to prove, that the people are essentially good, and that knowledge is rapidly advancing to that degree of perfectibility, when the proud distinctions of sophisticated fools will be eclipsed by the mi[l]d rays of philosophy, and man be considered as man – acting with the dignity of an intelligent being’. Tomaselli urges us to see Wollstonecraft’s feminism as part of a larger project of rethinking and reshaping both men and women so they could reach their potential as intellectual and moral beings.

However, Wollstonecraft’s thinking is not entirely coherent. The fact that she was very often writing up against a deadline and against other people in book reviews and ‘ripostes’ led her, as Tomaselli admits, ‘to adopt an adversarial tone, and caused her to be eager to contest the views of others rather than to calmly analyze and clarify her own’. Tomaselli constructs her holistic view of Wollstonecraft by inferring her philosophy from hints and partially developed arguments evolved in different contexts. The effect is sometimes bitty. Rather than offering a reading of individual works or proceeding chronologically through her career, Tomaselli traces the ways in which themes are treated across the body of her work, trying to create a picture of the mind of the person who wrote them. Thus, she pieces together Wollstonecraft’s comments on the various arts and her thoughts on the imagination that underpin them all. She also considers Wollstonecraft’s statements on racism and slavery and sees them as part of an exploration of systems of inequality. Mostly, the approach is illuminating, but sometimes it seems as if sections were put together with judicious use of the indexes of Wollstonecraft’s works. This is especially true of the opening chapter, called ‘What She Liked and Loved’. Designed to counter the view that Wollstonecraft was a spoilsport, the sections on her various enthusiasms – theatre, painting, poetry, nature and so on – read more like a commonplace book than an argument.

Nonetheless, this is an ambitious and valuable synthesis of disparate elements in the career of a woman whose life and thought were both revolutionary. Tomaselli argues that A Vindication of the Rights of Woman ‘should not eclipse the rest of her corpus, nor can it be fully appreciated outside of it’. In doing so, she encourages readers to break down barriers, just as Wollstonecraft herself did.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

The son of a notorious con man, John le Carré turned deception into an art form. Does his archive unmask the author or merely prove how well he learned to disappear?

John Phipps explores.

John Phipps - Approach & Seduction

John Phipps: Approach & Seduction - John le Carré: Tradecraft; Tradecraft: Writers on John le Carré by Federico Varese (ed)

literaryreview.co.uk

Few writers have been so eagerly mythologised as Katherine Mansfield. The short, brilliant life, the doomed love affairs, the sickly genius have together blurred the woman behind the work.

Sophie Oliver looks to Mansfield's stories for answers.

Sophie Oliver - Restless Soul

Sophie Oliver: Restless Soul - Katherine Mansfield: A Hidden Life by Gerri Kimber

literaryreview.co.uk

Literary Review is seeking an editorial intern.