Lucy Lethbridge

Mistress of Disguise

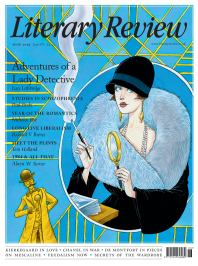

The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective: Secrets and Lies in the Golden Age of Crime

By Susannah Stapleton

Picador 370pp £20

Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers.

Stapleton’s quest started, as all modern searches must, with Google. Pondering one day whether there was a history of women employed as private investigators, Stapleton, an avid reader of detective fiction, reached for her laptop. A few clicks later, she came up with a photograph of ‘London’s only Lady detective examining a piece of handwriting through a magnifying glass’. It was West. From then on, Stapleton pursued her quarry through libraries, archives and in the ever-expanding databases of the internet. One of the many surprising pleasures of this biography is how the author makes the reader feel the excitement of keyboard research, explaining how it has enlarged our access to unsung lives. Record offices and census records, the possibilities of cross-referencing, making links and finding odd connections: they are all now increasingly available at a swipe. The moment an idea springs into her mind, Stapleton can explore it without booking a train ticket.

Her subject, however, proved extremely difficult to pin down. West, who set up her private detective agency in 1909, left behind a mass of false trails. She was a proficient self-publicist who wrote up highly embellished (often downright untrue) accounts of her adventures for newspapers. A typical story began: ‘My client was a foreign nobleman whose daughter, an only child, had left home. According to all reports she had become associated with people of the underworld.’ Yet West kept her own life almost entirely under wraps, airily referring to a family background populated by ‘barristers and solicitors’. In fact, she turned out not to have been called Maud West at all, though this is probably the least significant of the many revelations unearthed by Stapleton.

West was the product of a time of social change: the suburbs were growing to accommodate the expanding clerical middle classes and the role of women was changing rapidly. Stapleton interweaves what she has discovered about West herself with fascinating details about the new freedoms available to women and the accompanying social anxieties. Was this why detective novels were so popular in the interwar period? Did they reflect an anxiety about change, about strangers, about it being no longer easy to judge someone’s place in the world by their appearance? Stapleton finds that women had been employed as department store detectives for decades, paid to prowl shop floors posing as well-dressed shoppers. Viewed as less likely to arouse suspicion than men, they were also used by the police to infiltrate rings of fortune-tellers. One woman, she learned, worked undercover tracking down unlicensed vets.

West herself (according to her own, not always reliable account) took on a variety of disguises, many of them male, which meant she could go anywhere. She could pose as a monocled dandy, a bearded old buffer or a washerwoman. She could hang around street corners or enter pubs. Stapleton points out that there was a fad in the early 20th century for disguises and digs up evidence of specialist costume outfitters. She notes that ‘the boundaries that had once confined people to their “proper” station in life had become less solid and with the help of a cunning disguise, anyone could push against those walls and explore life on the other side’. The suffragettes had shown that women of any class could organise themselves; all that was required was resourcefulness and guile. For women of every type who had been brought up to resemble their mothers, it was liberating to try on the clothes of another kind of life. Stapleton also has an intriguing chapter on the huge popularity of theatrical male impersonators, such as the great Vesta Tilley.

The adventure of disguise also brought with it the possibility of an equally exciting brush with the underworld. ‘Nightclubs, drugs and foreigners’, Stapleton observes, were the moral terrors of the 1920s; young girls were warned of dissembling men who hung around railway stations waiting to lure them into white slavery. Private detectives undertook mostly divorce work, but they also helped trap gigolos, gold-diggers, bogus spiritualists, scammers, shysters and fake matrimonial agencies. All these tell a story of new times and of postwar singletons, independent but also perhaps unworldly, lonely and vulnerable. There was a bracing optimism, a spirit of self-improvement, of lecture groups, evening classes and branch meetings. I enjoyed Stapleton’s description of the Efficiency Club for women, of which West was secretary (she once invited Dorothy L Sayers to speak on ‘efficiency in murder’).

West’s private life was difficult to unpick but turns out to have been rather more prosaic than her colourful career. Even so, the records offer up a range of subterfuges: one of Maud’s sons, for example, stole the identity of his uncle, a dentist, so that he could practise dentistry without passing the exams first. The wider history is occasionally a little broad-brush, but Stapleton has that most important skill: a feel for the everyday detail that makes the past come to life. She lists the items put up for sale by West in her local paper in Finchley: a tennis kit from Harrods, a lady’s bicycle and a Harley-Davidson with a sidecar. You could write a whole novel of the 1920s from that list, encompassing enthusiasms and fashions and the ebb and flow of middle-class fortunes. The Adventures of Maud West, Lady Detective is delightfully well written, with both sympathy and empathy; it is jaunty, engaging and witty without being arch. A triumph.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Richard Flanagan's Question 7 is this year's winner of the @BGPrize.

In her review from our June issue, @rosalyster delves into Tasmania, nuclear physics, romance and Chekhov.

Rosa Lyster - Kiss of Death

Rosa Lyster: Kiss of Death - Question 7 by Richard Flanagan

literaryreview.co.uk

‘At times, Orbital feels almost like a long poem.’

@sam3reynolds on Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, the winner of this year’s @TheBookerPrizes

Sam Reynolds - Islands in the Sky

Sam Reynolds: Islands in the Sky - Orbital by Samantha Harvey

literaryreview.co.uk

Nick Harkaway, John le Carré's son, has gone back to the 1960s with a new novel featuring his father's anti-hero, George Smiley.

But is this the missing link in le Carré’s oeuvre, asks @ddguttenplan, or is there something awry?

D D Guttenplan - Smiley Redux

D D Guttenplan: Smiley Redux - Karla’s Choice by Nick Harkaway

literaryreview.co.uk