Ritchie Robertson

No Way Home

Silent Catastrophes: Essays in Austrian Literature

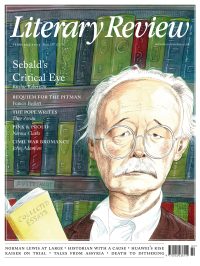

By W G Sebald (Translated from German by Jo Catling)

Hamish Hamilton 511pp £25

Since the deplorably premature death of W G Sebald in a road accident in 2001, Jo Catling, a former colleague of his at the University of East Anglia, has been among the most dedicated keepers of his flame. Her latest tribute to Sebald is a translation in a single volume of his two collections of essays on Austrian literature, Die Beschreibung des Unglücks (‘The Description of Misfortune’) and Unheimliche Heimat (‘Strange Homeland’). Written mostly in the 1980s, these essays preceded the semi-fictional works, culminating in Austerlitz (2001), that made Sebald internationally known. They represent something rare in German but common in English: literary criticism, occupying the space between academic study and journalistic discussion. And they say more, and say it more searchingly, profoundly and pithily, than a cartload of academic monographs.

Sebald rapidly became alienated from the old-fashioned Germanistik he encountered at the University of Freiburg in the early 1960s. The professors, he felt, had culpably failed to reflect on the relations between literature and the recent German past. He found intellectual and ethical stimulus in the thinkers of the Frankfurt School, particularly Theodor Adorno and the idiosyncratic, always marginal genius Walter Benjamin. References to Benjamin and a range of psychologists and sociologists pepper these texts, reinforcing Sebald’s own insights.

Why Austrian literature? Sebald was not Austrian, though his south German birthplace, Wertach, was within walking distance of the Austrian border. Austrian literature appealed to his feeling for marginality. Its major writers, from Franz Grillparzer via Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Kafka to Peter Handke, do not fit easily into the pattern of German literature, stretching from Goethe via Thomas Mann to Günter Grass. They excel, in Sebald’s view, in exploring psychological states ranging from obsession and melancholia to schizophrenic breakdown. One notably empathetic essay concerns an actual schizophrenic, Ernst Herbeck (1920–91), who was confined for fifty years in a mental hospital near Klosterneuburg, north of Vienna, where Sebald visited him. Herbeck wrote a large number of poems with enigmatic lines, such as ‘the raven leads the pious on’. Although these poems yield nothing to academic exegesis, they not only linger in the memory but may also, Sebald suggests, reveal the primitive processes through which poetic language arises.

Herbeck’s poems are at the furthest distance from the modern, bureaucratic, administered world which Sebald, like the Frankfurt School, wanted to resist. He traces its development in 19th-century bourgeois literature, in which Enlightenment reason is converted into prescriptive rationality, and emotional and erotic impulses are subjected to the discipline of bourgeois marriage. In Schnitzler’s Dream Story (travestied in Stanley Kubrick’s film Eyes Wide Shut), a bourgeois husband and wife separately explore their sexual fantasies. Sebald astutely notes that at the period it was written, men’s desires led downwards to prostitutes, or at least to available working-class girls, while women were tempted upwards to officers and (usually unsavoury) aristocrats. This observation is confirmed by the work of a German writer whom Sebald only mentions in passing, Theodor Fontane. His On Tangled Paths illustrates the first proposition and his Effi Briest the second. With similar scepticism, Sebald reads Hofmannsthal’s unfinished novel Andreas, supposedly a Bildungsroman depicting the path to personal integration, as a narrative about the dissolution of a weak and unstable self, haunted by sadistic fantasies, that reveals a crisis in bourgeois masculinity. A further stage in that crisis, schizophrenic breakdown, Sebald finds documented with great sensitivity in Peter Handke’s Die Angst des Tormanns beim Elfmeter (‘The Goalie’s Fear of the Penalty Kick’).

The essays from Sebald’s second book address a concept, Heimat (‘homeland’), that throughout the 20th century was heavily freighted with conservative nostalgia. Sebald points out that you only recognise your homeland once you have lost it. This happened in an exceptionally painful way to Hanns Mayer, a Jew entirely assimilated into Austrian provincial society, who fled Austria for Belgium after the Anschluss but was eventually detained and sent to Auschwitz. He survived and returned to Belgium, where he lived as Jean Améry. He revisited Austria only once, in 1978, and committed suicide in a hotel in Salzburg. Sebald cautiously speculates that Améry was in the end seeking ‘a solution to the insoluble conflict between Heimat and exile’.

Comparable, though less painful, is the situation of the Jews depicted in 19th-century ‘ghetto fiction’. Assimilated Jews from eastern Europe, the greatest writer among them being Karl Emil Franzos, wrote about the shtetls they had left behind with a mixture of condescension, amusement and disgust. They sought a better Heimat in western Europe, which they supposed to uphold the values of the Enlightenment, but, once there, they could only write about Jewish themes. At the end of this line stands Joseph Roth, who left the shtetl to study and live as a journalist in Austria and Germany. In The Radetzky March, he celebrates the lost homeland of pre-1914 Austria while exposing its hollowness. In late stories, such as The Leviathan, he writes about eastern Jews with a sympathy devoid of condescension. Sebald’s exploration of ghetto fiction, a body of writing unknown to most Germanists, confirms his independence of the literary canons prescribed by academia.

Two essays here deal with Kafka, who is often mentioned in passing and was clearly, like Benjamin, one of Sebald’s touchstones. One, on ‘authority, messianism and exile in Kafka’s Castle’, starts with the profession of the protagonist, a land surveyor, the term for which in Hebrew is very similar to that for ‘messiah’. The other explores the motif of death, which is omnipresent in The Castle. It is not an academic interpretation, but rather a meditation on the novel’s imagery and its implications. Sebald’s may be the best approach to Kafka, whose fiction continually defies the academic urge to gather from it a univocal meaning.

Finally, we have an essay on an author popular in the 19th century but seldom read or studied at present, Karl Postl, alias Charles Sealsfield. Postl, a monk in Moravia, ran away from his monastery to pursue worldly ambitions. Unable to return to Austria, he spent some years in the United States, where he changed his name, acquired a plantation worked by slaves and wrote numerous novels in the tradition of James Fenimore Cooper. He lived later in Switzerland and passed as a wealthy American. In Postl’s defence of American expansion and the extermination of inferior races, Sebald perceives an anticipation of the Holocaust, and his descriptions of American nature touch on a recurrent theme in Sebald’s work: our destruction of the natural environment.

Catling’s translation, clearly a labour of love, admirably conveys Sebald’s distinctive tone. A strange flaw, however, is the treatment of certain forenames. The architect Adolf Loos becomes ‘Alfred Loos’. One fictional character correctly introduced as Ronald promptly has his name changed to ‘Roland’, and Handke’s protagonist Filip Kobal twice becomes ‘Felix’. Quibbles aside, Catling has made available a body of literary criticism of the highest quality, though one can only really appreciate it if one is familiar with the texts discussed. Fortunately, most are available in English, the details being provided in Catling’s notes.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

The latest volume of T S Eliot’s letters, covering 1942–44, reveals a constant stream of correspondence. By contrast, his poetic output was negligible.

Robert Crawford ponders if Eliot the poet was beginning to be left behind.

Robert Crawford - Advice to Poets

Robert Crawford: Advice to Poets - The Letters of T S Eliot, Volume 10: 1942–1944 by Valerie Eliot & John Haffenden (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

What a treat to see CLODIA @Lit_Review this holiday!

"[Boin] has succeeded in embedding Clodia in a much less hostile environment than the one in which she found herself in Ciceronian Rome. She emerges as intelligent, lively, decisive and strong-willed.”

Daisy Dunn - O, Lesbia!

Daisy Dunn: O, Lesbia! - Clodia of Rome: Champion of the Republic by Douglas Boin

literaryreview.co.uk

‘A fascinating mixture of travelogue, micro-history and personal reflection.’

Read the review of @Civil_War_Spain’s Travels Through the Spanish Civil War in @Lit_Review👇

John Foot - Grave Matters

John Foot: Grave Matters - Travels Through the Spanish Civil War by Nick Lloyd; El Generalísimo: Franco – Power...

literaryreview.co.uk