Georgina Adam

Not Worth a Can of Soup

Warhol after Warhol: Power and Money in the Modern Art World

By Richard Dorment

Picador 288pp £20

Art Exposed

By Julian Spalding

Pallas Athene 320pp £17.99

These are two very different books, and each shines a light on different aspects of the art world. One focuses on a single case in which the author was tangentially involved from the beginning; it reveals much about the power of money in the art world, as well as its opacity and deceptions. The second is a lively romp through the art world in Britain, offering a series of portraits of the many people the author met over decades as a curator, museum director, writer and highly controversial commentator. Along the way, he recounts meetings with royalty, artists, museum professionals, politicians and the occasional celebrity. Few come out unscathed.

In Warhol after Warhol, Richard Dorment, former chief art critic for the Daily Telegraph and also an art historian and curator, retraces the tale of a Warhol portrait that was ‘double denied’, in other words twice rejected by the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board, which had been set up in 1995 by the Andy Warhol Foundation. The owner, an American film producer called Joe Simon, waged a ten-year battle to get this judgement reversed.

Dorment’s story starts in 2003 with ‘a voice on the line’ – a call from Simon asking him to take a look at a couple of pictures by Warhol he owned. Dorment was busy at the time and not particularly interested but agreed to meet Simon the following week. It was then that he saw the two Warhols: Red Self-Portrait and a ‘Dollar Bill’ piece, a collage of banknotes stuck onto a small canvas. Both had been rejected by the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board as fakes.

From then on, Dorment became sucked into Simon’s increasingly complicated and fraught relationship with the board, which at the time was the authority on whether something was genuine, and so worth millions, or a virtually valueless fake (the board was eventually disbanded, mainly as a result of the Simon case).

Dorment paints a compelling portrait of Simon, who as a teenager started as a ‘gofer’ to fashion supremo Diana Vreeland and other society dames and was one of the groupies buzzing around Warhol at the end of his life. He then became a successful film producer. ‘The obsessive-compulsive behaviour he exhibited in his pursuit of the Warhol case turned up in other aspects of his life,’ Dorment writes.

That behaviour almost destroyed Simon. In his zeal to prove the authenticity of his works, he dug ever deeper into the circumstances around the making of his Red Self-Portrait, one in a series of eleven silkscreens Warhol produced in 1965. The crux of the matter was the extent of the artist’s involvement. Determined to challenge the decision of the board, Simon finally took it to court. Dorment writes, ‘The decks were now cleared for an epic battle that would become a milestone in the history of a new branch of the legal profession: art law.’ His description of the court case – of the big legal guns rolled out to discredit Simon, the lies they told and the ‘mud and misinformation’ slung at him – is agony to read. Dorment himself was the target of threats and intimidation, he says.

Dorment followed the story closely, notably writing seven articles about it in the New York Review of Books. He is an excellent writer: ‘Each time I thought the story was dead and done with, Wachs [the board chairman], like some human defibrillator, jolted it back to life.’ The story is laid out carefully and logically, in great detail but always very readably.

The revelations are shocking: Simon being encouraged to re-present a work that the board had already determined it would reject; the board’s underhand tactics concerning other works in the same series; the lack of separation between the foundation’s commercial and philanthropic arms; the mistakes it made; the evidence it manufactured; the millions of dollars it paid to the sales agent Vincent Fremont; the reclassification of allegedly inauthentic works so that the foundation could sell them on.

Is there another side to the story? No doubt the Warhol Foundation would say so, but Dorment lays out the facts in convincing, indeed forensic detail. Simon is a complicated person – and the second work was, it turned out, a fake. All the same, I closed the book saddened by the story it tells of a foundation pumped with money, entitlement and possible conflicts of interest, and apparently immune from oversight and criticism.

*

Julian Spalding spent his career working in the public sector as a director of galleries in Sheffield and Manchester, then as director of Glasgow Museums. He left the museum world in 1999. He has written extensively about art and museums: this is his sixth book. In it, he looks back over a lifetime of battles, interactions and encounters with everyone from Jacques Chirac to David Hockney, taking in Queen Elizabeth II, Neil MacGregor and Beryl Cook on the way. He also writes about those he would like to have met, such as John Ruskin and Salvador Dalí.

The book is arranged alphabetically by name; each chapter stands on its own. Spalding is known as an acerbic critic with a very clear agenda: he thinks that conceptual art is a ‘con’, the art of painting is sorely neglected and ‘the whole multi-million-pound conceptual art investment market is a bubble that is about to burst’. He once applied to be director of Tate but discovered that he didn’t have a chance, which he ascribes partly to his humble beginnings. He also recounts some of the initiatives he put forward which were not followed, such as a Picasso show at the Royal Academy and a change in the date limit for works in the National Gallery to beyond 1900.

His bitterest words are reserved for Sir Nicholas Serota, the former director of Tate, whom he blames for the ‘rot’ in art in Britain. ‘We didn’t see eye to eye from the start,’ he states, going on to describe him as ‘an odd man to look at, more bone than flesh, tall, thin and vertical. The only horizontal line in him is the closed aperture in his mouth, which is thin-lipped and straight.’ According to Spalding, ‘Serota’s whole philosophy of modern art, and indeed his whole curatorial practice, is based on his belief in Duchamp, in particular his act of sending a urinal into an exhibition, claiming anything can be a work of art if an artist says it is.’

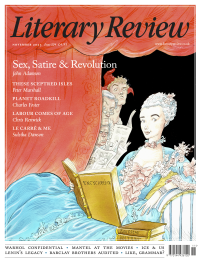

Spalding describes how at an international curators’ conference, when he said he would be putting works by Beryl Cook, painter of cheerful, saucy women who had scant critical acclaim, in the collection of the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow, Serota ‘solemnly announced, “There will be no Beryl Cooks in Tate Modern.”’ It is certainly no coincidence that the image on the cover of the book is by Cook (it in fact originated as a birthday card painted for Spalding).

Serota is not the only person Spalding skewers. He also takes swipes at Mrs Thatcher, Marcel Duchamp (he of the urinal) and Sir Roy Strong. But those he dislikes are easily outnumbered by those he does like, among them Henri Cartier-Bresson, Martin Handford (of Where’s Wally? fame), Niki de Saint Phalle, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Pablo Picasso and, surprisingly for a staunch republican, the late queen.

In his professional career, Spalding seems sometimes to have been his own worst enemy, fighting for but often failing to impose his vision of art in Britain. But his stories are always interesting, lively and well written, giving an insight to the art world as he experienced it.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk