Peter Marshall

Notes from the Atlantic Archipelago

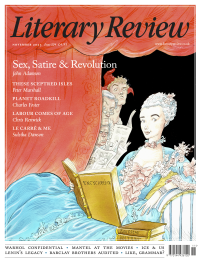

The Britannias: An Island Quest

By Alice Albinia

Allen Lane 512pp £25

In July 2023 Orkney Islands Council voted to explore alternative governmental arrangements for the archipelago. One option proposed by the council leader was for it to become a self-governing territory of Norway, the kingdom which lost control of Orkney to Scotland in 1468. The episode – in reality, a smart political stunt in a row over the Scottish government’s transport policy – attracted extraordinary international attention. In the UK press, it was treated with an uneven mixture of constitutional soul-searching and patronising amusement at the Passport to Pimlico-style antics of the Orcadians.

The episode came too recently for Alice Albinia to allude to it in her book, a stylish and intriguing cultural-historical survey of the multiple island communities threaded around the coasts of Britain, but it would have been grist to her mill. For most people, much of the time, Britain’s islands remain out of sight and out of mind, but they always retain the capacity to surprise and to pose challenging questions about identity.

The British (or should that be the English?) are culturally conditioned to think of themselves as an ‘island nation’, a concept nurtured in Shakespeare’s patriotic evocation of ‘this sceptred isle’, in Churchillian rhetoric of wartime resistance and in the emotional mood music of Brexit. ‘Great Britain’ may indeed be the name of an island, but, as Albinia rightly points out, the British polity is not, and never has been, mono-insular. There are literally thousands of islands in what scholars call the ‘Atlantic Archipelago’, a phrase which, unsurprisingly, has never taken off with the general public. In relatively recent times, probably over two hundred of these islands have been inhabited, their populations speaking a variety of languages other than English: a version of Old Norse known as Norn in Orkney and Shetland, Gaelic in the Hebrides and Rathlin Island off the coast of Ulster, Manx in the Isle of Man, Welsh in Anglesey, Cornish in the Scilly Isles, and Jèrriais and Guernésiais, distinct vernaculars derived from Norman French, in the Channel Islands.

Even setting to one side the historically neuralgic relationship with the neighbouring island of Ireland, Britain’s insular periphery has from at least the time of the Romans presented difficulties for authorities wishing to centralise. The islands have been places of contested sovereignty and of legal and constitutional anomaly, of political, social and linguistic marginalisation and of remarkable cultural, economic and spiritual creativity. Albinia’s book – part cultural history, part travelogue, part memoir – takes its readers on a zigzag odyssey in and out of the island perimeter, and backwards and forwards in time. We start off in Orkney and in succeeding chapters we follow the author to Anglesey, the Isle of Wight, Iona, the Kentish Isle of Thanet, Shetland, Lindisfarne, the Inner Hebrides, the Scilly Isles, the Isle of Man, the Outer Hebrides and the Channel Islands. In a neatly ironic resolution, Albinia brings her account to a close in Westminster, historical heart of the centralising state, but itself once an island, encircled by the Thames and the streams of the River Tyburn.

The journey leads in all kinds of directions. There are extended discussions of 18th-century smuggling in the Isle of Man, of fishing management in modern Shetland and of the Channel Islands’ painful reckoning with the legacies of Nazi occupation. A thread running through the narrative is the contention that Britain’s islands are usually places possessing deep historical associations with female power and that attention to their distinctive histories and cultures helps uncover the ways women have been excluded from mainstream accounts of Britain’s past.

The case is powerfully presented and persuasive, up to a point. There is no disputing the patriarchal and frequently misogynistic character of medieval and post-medieval Christian society. But the suggestion that women routinely enjoyed enhanced prestige and authority in pre-Christian Celtic polities involves some selective deployment and interpretation of sources, and becomes increasingly speculative as we move further back into the Neolithic. In fairness, Albinia is aware of this: ‘The evidence can only take us so far. After that we have to surrender ourselves to the lost possibilities, to reflect on everything that was deliberately or inadvertently repressed, to dream of alternative dimensions.’

Historians of a more empirical stamp, not all of them male, might experience some discomfort here, as well as with the unabashed self-referentiality of Albinia’s scholarship and writing. The idea for the book began to gestate when she discovered the etymological kinship between her own name and that of mythical Albina, the ‘white goddess’ who supposedly bestowed on Britain the designation ‘Albion’. The Britannias belongs firmly to the genre that treats travel writing as a mode of self-discovery: we learn much about Albinia’s relationship with her daughters, the disintegration of her marriage and her own increasing determination as a woman in Britain to be recognised and acknowledged, to be ‘seen’.

No one could accuse Albinia of lacking commitment to her project. In the course of researching the book, she moved to Orkney for fourteen months, working as a cleaner in a harbour-front Kirkwall hotel and as an archaeological volunteer at the Ness of Brodgar, the extraordinary ritual site which over the course of the last two decades has helped rewrite the history of Neolithic Britain. Elsewhere, we accompany her on a sponsored pilgrimage walk to Lindisfarne, on a Gaelic singing course in Skye, as a volunteer on a charity sailing trip for young people through the Hebrides, on an all-female retreat in Iona (where she learns to be less judgemental about New Age spirituality) and as part of the costumed entourage of England’s last surviving horse-drawn show, making its stately way from Stonehenge to the Isle of Thanet. In between, we share the experience of sleeping out under the stars at various Iron Age monuments and listen in on enlightening conversations with various lively characters and island luminaries, exchanges which seem delightfully serendipitous and picaresque but must often have been meticulously arranged.

The effect is kaleidoscopic but ultimately disarming. Albinia is a novelist as well as a writer of non-fiction, and her prose is never less than enjoyable and at times delicately lyrical. In the Orcadian island of Hoy, ‘rain hits the roof of our one-storey house like a thousand Norse arrows’. An ambitious book of this kind inevitably draws heavily on the scholarship of others, but Albinia has read widely across an impressive range of sources and proves erudite and insightful on a variety of topics. In the parts of the historical story I am most familiar with, I spotted remarkably few misapprehensions, though Albinia does appear to subscribe to the popular fallacy that witches were burned at the stake in England; in fact, scarcely less horribly, as convicted felons they were hanged. The shadowy figure of Triduana (or Tredwell), heavenly patron of a healing chapel on Papa Westray, is several times described as an Orcadian saint, but such sources as we have suggest that she originated in Greece and that before the Reformation her cult spread right across Scotland.

The connectedness of these islands to what was happening elsewhere is as much a part of the story Albinia wants to tell as their alleged remoteness. Her autobiographical approach undoubtedly helps get that message across. In the end, she want us to think of ‘islandness’ as an aspect of the human condition, at least in the modern West. We are suspended between the impulse to be part of the busy world and the temptation to retreat from it. Those of us in long-term exile from an island home, never quite happy with a decision not to return, will know instinctively that she is right.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Though Jean-Michel Basquiat was a sensation in his lifetime, it was thirty years after his death that one of his pieces fetched a record price of $110.5 million.

Stephen Smith explores the artist's starry afterlife.

Stephen Smith - Paint Fast, Die Young

Stephen Smith: Paint Fast, Die Young - Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon by Doug Woodham

literaryreview.co.uk

15th-century news transmission was a slow business, reliant on horses and ships. As the centuries passed, though, mass newspapers and faster transport sped things up.

John Adamson examines how this evolution changed Europe.

John Adamson - Hold the Front Page

John Adamson: Hold the Front Page - The Great Exchange: Making the News in Early Modern Europe by Joad Raymond Wren

literaryreview.co.uk

"Every page of "Killing the Dead" bursts with fresh insights and deliciously gory details. And, like all the best vampires, it’ll come back to haunt you long after you think you’re done."

✍️My review of John Blair's new book for @Lit_Review

Alexander Lee - Dead Men Walking

Alexander Lee: Dead Men Walking - Killing the Dead: Vampire Epidemics from Mesopotamia to the New World by John Blair

literaryreview.co.uk