Nicholas Roe

Obsession of an Opium-Eater

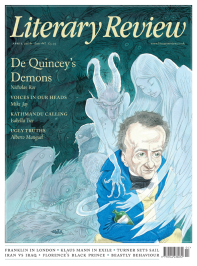

Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey

By Frances Wilson

Bloomsbury 397pp £25

‘This event of his life – his resort to opium – absorbed all the rest. There is little more to tell in the way of incident. His existence was thenceforth a series of dreams, undergone in different places.’ So the Daily News accounted for Thomas De Quincey, author and opium-eater, on his death in December 1859. Scanty ground for a biography, one might think. Yet De Quincey’s opium habit was a story that absorbed many readers at the time. Taken as a ‘blue pill’ or in alcohol as laudanum, opium was an effective panacea that hooked William Wilberforce and Dorothy Wordsworth, Sara Coleridge, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Charles Dickens and many thousands more. Opium-induced reveries gave us the visionary landscapes of Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’ and Keats’s ‘Ode on Indolence’, before prolonged use of the drug helped to destroy both poets. As Frances Wilson cheerfully observes, 19th-century Britain was ‘marinated in opium’.

Like Coleridge, De Quincey has come down to us as a Romantic genius wrecked in a mist of opium – his family and friends estranged, his major works left as fragments. Born in Manchester in 1785, his childhood was overshadowed by the deaths first of his beloved sister Elizabeth, then of his father – a prosperous, book-loving businessman. His mother, a ‘lady architect’, was remote, snobbish and a stickler for order. Her chief legacy to her children was an ingrained sense of guilt. As a widow she moved to lodgings in fashionable Bath, where she gentrified the Quincey surname by adding ‘De’ to suggest a knightly lineage. Being a De Quincey opened doors and gave her access to Hannah More’s evangelical circle. Aged sixteen, Thomas ran away from Manchester Grammar School and spent months on the road in Wales and London; later, a promising career at Oxford ended when he bunked off an examination. As obsessive as he was evasive, De Quincey was often tempted to cut and run, and opium would prove the most seductive escape of all.

De Quincey was one of the first readers to recognise the significance of Lyrical Ballads. His earliest contact with William Wordsworth came in 1803. In a carefully drafted letter he introduced himself as an admirer, sought the poet’s friendship and expressed ‘reverential love’. When the poet eventually replied, he wrote of his ‘kind feelings’, cautioned his young correspondent that friendship must be ‘the growth of time and circumstance’, and said he would be happy to meet. In time De Quincey became a star-struck tenant in Wordsworth’s former home, Dove Cottage, in Grasmere. Of De Quincey’s many houses, this one initially brought him most gratification – the cottage was ‘sacrosanct’ for Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, and he believed he was blessed to be its next occupant when he moved there in 1809. Time and long acquaintance would teach him otherwise, however, as he came to realise that a poet and his works can have distinct – even opposite – identities. As Wordsworth lapsed into coldness and silence, De Quincey discovered that those wonderful poems had been composed by a man who, he now saw, combined colossal egotism with a physically repulsive ‘meanness’. While still living in Dove Cottage, De Quincey married his servant Margaret Simpson and began a family that would grow to eight children.

De Quincey’s fateful ‘resort to opium’ began, according to him, on a cheerless Sunday in 1804, when he swallowed it to relieve rheumatic pain. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, his autobiographical masterpiece, recasts this routine event and magnifies it into a uniquely personal odyssey of taboo, transgression, divine enjoyment and demonic agony: ‘In an hour, oh! Heavens!’ he recalled. ‘What an upheaving, from its lowest depths, of the inner spirit! What an apocalypse of the world within me! … Here was a panacea … for all human woes.’ A few drops of laudanum created reveries of ‘most exquisite order, legislation, and harmony’; his pain vanished, self-possession gathered and all the conflicts, self-recrimination, fears and anxiety that had assailed his life dissolved into visions of beatific calm. Visionary scenes from his childhood revived amid torrents of sunlight, ‘exalted, spiritualized, and sublimed’. No longer a guilty thing constantly running away, he could voyage forever through oceans of elaborate intellectual pleasure. Such were the astonishing effects of laudanum, until addiction and terrifying ‘Pains of Opium’ initiated a long farewell to happiness and peace of mind.

Watching her father down another stupefying dose, his daughter Margaret Thomasina invented her own word for daddy’s ‘medicine’. She called it ‘yaddonum’. De Quincey’s need for it was possibly rooted in feelings of physical inadequacy. In person he was ‘unfortunately diminutive’, according to Dorothy Wordsworth – who was the same height; wiry and sickly, he was barely there at all. As the ‘English Opium-Eater’, he became a giant, discovering passageways into his imagination and establishing his own literary identity. Grevel Lindop and Robert Morrison have already given us two fine biographies of this strange, contradictory creature and Guilty Thing opens new perspectives on his long, troubled voyage from riches to rags to posthumous fame.

The book circles around De Quincey’s fixations – murder, Wordsworth and The Prelude (he read it in manuscript, decades before publication) – and it opens with an account of the notoriously bloody murders at Ratcliffe Highway in London on 7 December 1811. Wilson’s chapter titles echo sections of Wordsworth’s autobiographical epic: ‘Residence in London’, ‘Summer Vacation’, ‘Imagination, Impaired and Restored’. Both Coleridge and De Quincey were fascinated by what grisly killings revealed about a murderer’s mind – a topic Wordsworth also explored when writing of his own role in the French Revolution. ‘There must be some great storm of passion, jealousy, ambition, vengeance, hatred’, De Quincey said. The murderer must also, like Robespierre, have the transgressive power to ‘rid himself of fear’. In later years, De Quincey would revisit the Ratcliffe Highway killings in a series of three essays ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’. The first of these, Wilson contends, designedly targets Wordsworth in its darkly delicious speculation that at some point in the past ‘the poet was a murderer’.

Murderous storms also lurked in the heart of Grasmere. Wilson allows us to see the opium-eater sitting alone and dejected at Dove Cottage – now a scene ‘most tempestuous and bitter within [his] own mind’ – as realisation dawned that he had merely replaced Coleridge as ‘Wordsworth’s inferior friend’. Seizing an axe, De Quincey dashed up the garden and demolished a summerhouse that had been lovingly created by Wordsworth and his sister. The date was 3 December 1811, the same week as the Ratcliffe Highway killings.

Perhaps, as Wilson speculates, De Quincey’s storm of vengeance was a devastating consequence of reading The Prelude. His furious recoil had shattered one of Wordsworth’s creations; although he would retain the lease of Dove Cottage until 1835 (he used it as a store for books), he could now emerge as an independent writer and thinker, brazenly raiding this unpublished work for his own creative ends. De Quincey would go on to compose perceptive essays on Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s poetry; he also opened their pasts to public scrutiny in his scandal-raking Autobiographical Sketches and Recollections of the Lake Poets. It was De Quincey who broadcast the facts of Wordsworth’s ‘slovenly’ appearance and Coleridge’s plagiarisms, while also mercilessly castigating his fellow addict’s recourse to opium for ‘luxurious sensations’. Unlike William Hazlitt, though, De Quincey was not a ‘great hater’ who nurtured lifelong animosities. In the end, Wilson surmises, his foremost emotion was not vindictive hatred so much as disappointed love.

His last years were spent with his family at Lasswade, south of Edinburgh, where Margaret took care of his financial affairs. He received royalties from American and British editions of his work. When he died at the age of seventy-four, still tippling his yaddonum, he had outlived almost all his contemporaries – even Leigh Hunt, who went to his grave in August 1859, four months before him. And De Quincey’s achievement has endured. His introspective techniques have influenced numerous later writers, from Edgar Allan Poe and Virginia Woolf to Bob Dylan and Paul Muldoon.

Guilty Thing brings triumphantly into focus a life racked by opium’s insidious effects – ecstasy twined around obsession, confused passions, disintegrations, depths below depths – all played out in dreamscapes and dazzling, self-revelatory prose. Beautifully crafted, Frances Wilson’s narrative sets up patterns, mirrors and doublings that make multiple intersections between De Quincey’s inner and outer worlds. An impressive contribution to literary biography, her book amounts to the most ‘De Quinceyan’ account of De Quincey we are likely to see.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk