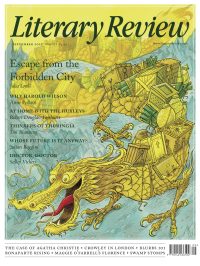

Julia Lovell

Operation Hanging Scroll

Fragile Cargo: China’s Wartime Race to Save the Treasures of the Forbidden City

By Adam Brookes

Chatto & Windus 382pp £25

Adam Brookes’s thrilling new book tells for the first time in English the epic story of a sixteen-year quest by curators, archaeologists, scholars and politicians to protect the irreplaceable artistic treasures of the Forbidden City from the ravages of invasion and civil war. He has uncovered the kind of history deserving of a cinematic blockbuster. Approximately 250,000 priceless artefacts – porcelain, silks, paintings, bronzes – somehow escaped destruction by fire, water, moths and termites on a journey of 15,000 miles, being transported by train, boat, lorry, raft and carrying pole ‘up rivers and across mountain ranges, through famine and war’.

The story begins amid the turmoil of early 20th-century China, with fights over the ownership of the Forbidden City’s peerless collection. For centuries, China’s emperors had hoarded within the palace’s vermilion walls some of the most exquisite arts and crafts of the empire. By the end of the 18th century, they had amassed more than a million objects.

But the old imperial system suddenly collapsed in 1912, giving way to a revolutionary republic in which power was really held by regional armies. For another dozen years, the last emperor, Puyi, who had abdicated, continued to live within the Forbidden City and to treat its art as his personal property, smuggling objects out to sell to Chinese and international collectors to cover his household expenses. In 1924, Puyi and his straggling retinue of wives, eunuchs, courtiers and servants were brusquely expelled from the Forbidden City by the latest warlord to take control of Beijing. To near-universal surprise, this warlord did not plunder the art collection to pay his soldiers but rather commissioned a meticulous inventory from the capital’s top scholars.

He then turned the Forbidden City into the Palace Museum, opening it to the public. What had once been the private collection of a single ruling family became almost overnight the symbolic property of the Chinese people.

Only a handful of years later, the Chinese state – by this point nominally unified by the Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang – faced the very real threat of destruction. Japanese imperialists grabbed and colonised swathes of northeast China, pushing ever closer to Beijing. In the early 1930s, Ma Heng, director of the Palace Museum, ordered the cream of the collection to be evacuated to the south. He had correctly diagnosed the danger posed by Japanese expansionism: between 1937 and 1945, Japanese armies came to occupy at least a quarter of China’s vast territory, leaving between fourteen and twenty million Chinese dead and creating as many as a hundred million refugees. The wonders of the Palace Museum set off on an reverse-L-shaped route, first southeast and then, after the Japanese invasion, along the Yangtze River – floating with unmoored mines – and deep into the undeveloped western hinterland, where the resisting Chinese Nationalist government had made its capital. Along the way, the collection and its caretakers narrowly evaded the Japanese ‘Rape of Nanjing’ and the firebombing of Changsha. The art had so many narrow escapes that curators ‘began to wonder if the objects … were possessed of some sort of spirit or soul protecting them’.

The Japanese surrender in September 1945 did not bring these journeys to an end. Between 1945 and 1949, the insurgent Chinese Communist Party pushed the Nationalist government out of the mainland and onto Taiwan, where it formed an independent sovereign state. The cream of the old imperial collection travelled with the exiled government. Today, it is exhibited in the dazzling National Palace Museum on the outskirts of Taipei, one of the great art galleries of the world.

Brookes is a writer of many facets – a lauded journalist and novelist – and he has a sure eye for the kind of luminous detail that can bring a story like this to life. During Beijing’s freezing winters, scholars catalogued with the ‘ashy taste of ink’ in their mouths because the only way to prevent their writing brushes freezing solid was to suck on them. On the steamer carrying the collection south along the Yangtze, stowaways played mah jong by candlelight next to crates of priceless and highly flammable paintings and books. Brookes writes beautifully about art and objects: the way that long handscrolls draw the viewer into their visual and narrative worlds; the exhausting meticulousness required to fire top-quality porcelain; the exquisite animation in Chinese nature painting; the aesthetic and moral power of art in the Chinese tradition.

Brookes also brilliantly humanises his story, telling a ‘tale of confusion and bureaucratic rivalries, of shaky improvisation and clouded judgement’. Along the way, we learn much about the chaos and complexity of wartime China. Outside the cities controlled by an aspiring central government, China often felt to Palace Museum workers like ‘a desolate, unpredictable country, a place of unintelligible dialects, venal local officials … marauding bandits’. Brookes’s curators experienced the same terrors as hundreds of millions of other Chinese people during the Japanese invasion: ‘the sound of the air-raid siren … the growl of an approaching bomber formation, the unique acid-sweet stench of a burning street’. After the expulsion of the Nationalists in 1949, Ma Heng, the saviour of China’s artistic heritage, was persecuted by the Communist Party for his service to the wartime Nationalist state, dying dejected and isolated in 1955.

So much more than a work of art history, Brookes’s book illuminates the exceptional dramas of the Chinese front in the Second World War, a theatre of the conflict that is still insufficiently understood by British readers and which continues to cast a long shadow over

East Asia.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Juggling balls, dead birds, lottery tickets, hypochondriac journalists. All the makings of an excellent collection. Loved Camille Bordas’s One Sun Only in the latest @Lit_Review

Natalie Perman - Normal People

Natalie Perman: Normal People - One Sun Only by Camille Bordas

literaryreview.co.uk

Despite adopting a pseudonym, George Sand lived much of her life in public view.

Lucasta Miller asks whether Sand’s fame has obscured her work.

Lucasta Miller - Life, Work & Adoration

Lucasta Miller: Life, Work & Adoration - Becoming George: The Invention of George Sand by Fiona Sampson

literaryreview.co.uk

Thoroughly enjoyed reviewing Carol Chillington Rutter’s new biography of Henry Wotton for the latest issue of @Lit_Review

https://literaryreview.co.uk/rise-of-the-machinations