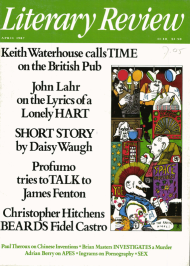

Christopher Hitchens

Self-Castrated Beaver

Castro

By Peter Bourne

Macmillan 332pp £14.95

I ONCE SAW the bearded one – el barbudo – and was close enough to touch him. It was at a rally in Santa Clara on 26 July 1968. The murder of Che Guevara was a recent, vivid memory. The Vietnam war, horrifying enough at the time, was to get more ghastly yet. In Angola and Nicaragua, partisan groups were still engaged in what seemed an endless and quixotic battle against the Portuguese and American empires. Castro spoke proudly against these and other despotisms. But he also denounced the Soviet Union and its dismal block of coerced allies. He had seized the person of Anibal Escalante, chief Stalinist of Cuba, and arraigned him and his ‘microfaction’ for trial. Escalante, who had been semi-exiled as ambassador to Prague, found himself behind bars for his intrigues with Moscow. Was it possible that Cuba was keeping its promise, of equidistance between the superpowers and revolutionary internationalism à la Bolivar or Marti?

Almost exactly a month later, I watched the bearded one give yet another very long speech. Czechoslovakia, late home of Escalante, had been invaded. Cuba’s place in the time zone meant that we received the news very early in the morning. It was announced that Fidel would address the masses late that night. In the meantime, the organs of propaganda held to the careful neutrality they had observed between Brezhnev and Dubcek in the unfolding of the crisis. I thus had the unusual and perhaps unique experience of spending a whole day in a Communist state, with only one topic of conversation and no stated party line. Cuban public opinion was unmistakeably pro-Czech, and not merely because of the natural sympathy for the small nation. There was no wild applause when the embodiment of the revolution took the stand to announce, in a dull, dogmatic and feebly-argued speech that the Warsaw Pact forces were right. From that day to this there has been no significant, public division between Moscow and Havana. Cultural life in Cuba has also adapted itself to the shape that such an unanimity might suggest.

It was not ever thus. ‘He was almost Christ-like during this first simple pilgrimage in his love and concern for the people. He was drunk with triumph but glowingly so.’ These simple words from the pen of Edwin Tetlow, correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, were a fair sample of the rapture with which Cubans and many Westerners greeted Castro’s first entrance into Havana. And what of his troops? They were, wrote Tetlow of the Telegraph, ‘one of the best-behaved armies you could imagine. They were too good to be real … to a man they behaved impeccably.’

The phoney ‘philosophe’ Jean-François Revel says, in one of his sillier books, that capitalist regimes are judged by their record whereas revolutionary ones are judged by their promises. He means to imply a double standard by this sarcastic formulation, but if there is one it very probably works at the expense of revolutions. Castro did not come to power promising stability and a restoration of national pride- the two things that he has in fact delivered. He posed not as a caudillo but as a liberator, with no personal ambitions. Today, although Cuba is treated as a serious country and not as an offshore Mafia bordello, it still has the stigma of personal rule, with the personal ruler’s brother the acknowledged next in line. Peter Bourne says that Castro has been in power longer than anyone except King Hussein. I think he might find that General Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay has clung on tighter and longer – a comparison that presumably flatters neither man.

Still, there is a contest for the shortest-lived government in Latin America. The principal competitors for this honour include every administration formed by political forces hostile to United States hegemony. Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, Juan Bosch in the Dominican Republic, Joao Goulart in Brazil, Salvador Allende in Chile – every literate and illiterate person south of the border knows the story. Many of the present Sandinista leadership spent part of their exile in Chile under Allende (as Guevara spent part of his in Guatemala until the overthrow of Arbenz) and if you ask them about it they will tell you. ‘Stay in the middle of the road’, they say, ‘and you get run over without pity’.

Peter Bourne, who has served in the White House and at the United Nations, is rather bored with this kind of political analysis of the fate of revolution in Latin America and the Caribbean. As a psychiatrist, he prefers to work the special magic of his trade on the subject. His conclusion is that Castro must be understood as a product of Jesuit education. It is this, apparently, that furnishes him with a sense of destiny and with the gift of insight into the Cuban soul. Bourne says that he himself worked for the Carter administration at one point, and I’m rather inclined to believe him.

Psycho-history apart, this narrative does little more than recapitulate the various episodes that have led the Cuban revolution to its present economic and political impasse. It is not quite true to say that the Cubans have exchanged one dependency for another, because this would ignore the enhanced experience and stature their country has acquired in the meantime. It is nonetheless true that the ‘model’ is one that lacks volunteer emulators. Anyone interested enough to pursue that question should read Carlos Franqui’s memoir Family Portrait with Fidel, or the neglected minor masterpiece of observation Persona non Grata, by the Chilean radical Jorge Edwards.

One thing, however, does not change. On April 14 1961, the members of the Cuban exile invasion force set off for their rendezvous at the Bay of Pigs. As they manhandled their CIA arsenal into the vessels, at the port of Puerto Cabezas in Nicaragua, they were addressed by a local politician who exhorted them to bring back some hairs from Castro’s beard. This was perhaps the finest hour in the life of Luis Somoza.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Russia’s recent efforts to destabilise the Baltic states have increased enthusiasm for the EU in these places. With Euroscepticism growing in countries like France and Germany, @owenmatth wonders whether Europe’s salvation will come from its periphery.

Owen Matthews - Sea of Troubles

Owen Matthews: Sea of Troubles - Baltic: The Future of Europe by Oliver Moody

literaryreview.co.uk

Many laptop workers will find Vincenzo Latronico’s PERFECTION sends shivers of uncomfortable recognition down their spine. I wrote about why for @Lit_Review

https://literaryreview.co.uk/hashtag-living

An insightful review by @DanielB89913888 of In Covid’s Wake (Macedo & Lee, @PrincetonUPress).

Paraphrasing: left-leaning authors critique the Covid response using right-wing arguments. A fascinating read.

via @Lit_Review