Dorian Lynskey

Something Changed

Faster Than a Cannonball: 1995 and All That

By Dylan Jones

White Rabbit 476pp £25

Accelerate! A History of the 1990s

By James Brooke-Smith

The History Press 304pp £20

Last year Finneas O’Connell, the brother and creative partner of Billie Eilish, released a poignant song called ‘The 90s’, which fixated on a decade ‘when the future was a testament/To something beautiful and shiny’. O’Connell was born in 1997, so this wasn’t personal nostalgia; rather it was a latecomer’s envious longing for a time when, at least if you were young and living in the West, history seemed to be on your side. Some of his elders would agree. In former GQ editor Dylan Jones’s oral history Faster Than a Cannonball, Nick Hornby describes the Nineties as ‘the last time the [UK] was happy’, while Noel Gallagher mourns it as ‘the last great decade where we were free, because the internet had not enslaved us all’. Those were the days, my friend.

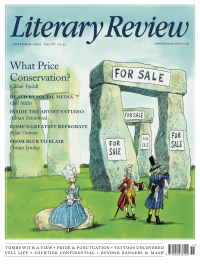

As the titles of Jones’s book and James Brooke-Smith’s Accelerate! indicate, one can read the decade as a period of brash, breathless momentum, especially in technology and the arts. Yet it would be equally true to see it as politically becalmed, a time when the neoliberal revolution was cemented in the fuzzier form of third-way politics – in Brooke-Smith’s words, ‘a slicker, more tasteful version of the 1980s’. All decades are Janus-faced. The collapse of the Berlin Wall and the attacks on the World Trade Center, the two events that bookend the 1990s, give an illusion of coherence to a chaotic and paradoxical decade. While those who lived through it tend to celebrate its explosive confidence, younger critics on the Left damn it for the complacency it induced and argue that we are now living with the crises – political, economic, technological – that the Nineties seeded.

Both interpretations are somewhat true, but you won’t find much ambivalence or (that essential Nineties quality) irony in Faster Than a Cannonball. Although Jones throws in a few sceptical voices, a quote from Blur’s Alex James captures the doggedly celebratory tone: ‘What a totally, utterly brilliant decade. It was certainly a time of peace and prosperity, and fun, when lunches lasted for days and Britain, particularly London, led the world.’ Hooray! Jones was a senior editor at the Sunday Times Magazine in 1995 and seems to have hung out with all of his interviewees, making the interstitial passages a kind of stealth memoir about his adventures with the glitterati. I’m glad he had a wonderful time, but even as someone who was twenty-one then (and whose retrospective essay about 1995 is quoted in the foreword), I grew weary of being told what bliss it was in that dawn to be alive.

Jones ostensibly focuses on 1995 – each month is given its own chapter, and a different theme is examined in each of these – but a full third of the book covers the periods either side of that annus mirabilis and a great deal of backstory is crammed into the book too. As Brooke-Smith observes, it was the ‘mini epoch’ before the mid-1990s economic boom that gave us rave, grunge, Britpop, the YBAs, the supermodels and the indie cinema revolution. The year 1995, you could argue, was more about consolidation than innovation, with hungry outsiders becoming the new status quo.

This is history as told by a small coterie of winners. If Jones’s claim that ‘the nineties chimed with the sixties in being a decade that was almost uniquely British’ is questionable enough, then his ambit is more parochial still. His book’s subjects are successful people, mostly white, mostly men, living in London. The Help album of 1995, which united stars in raising funds for children in war-torn places such as Bosnia, might have been a bridge to the world beyond the Groucho Club, but it only registers here because Kate Moss played tambourine on one track. Faster Than a Cannonball lacks the polyphonic vitality of the best oral histories, leaning too hard on long quotes from big names, including Noel Gallagher, Damien Hirst and Tony Blair. That’s okay when an eyewitness is as eloquent as Tracey Emin (‘This whole new generation of colour is the only way I can explain it. A brightness of things happening’) but less so when it’s Piers Morgan, who makes this unimprovably Partridgesque claim: ‘Probably the best night of the nineties was the opening of Planet Hollywood in Soho in 1993.’ Was it though?

The book’s myopia would matter less if it weren’t 476 pages long. Whole chapters are devoted to such you-had-to-be-there ephemera as men’s magazines and the easy-listening revival, and no fewer than four to facets of Britpop. Jones is broadly happy to repackage the glittering myth of Cool Britannia, but in presenting his thesis that the Nineties was as exciting and creatively fertile as the Sixties – Swinging London redux – he ends up underselling the more recent decade. You will read more here about David Bailey and Michael Caine than Goldie and Tricky; the Beatles loom larger than club culture. The comparison ultimately produces bathos, as we see the decade’s utopian promise smothered by money and cocaine rather than Nixon and Vietnam. As Jarvis Cocker sings in ‘Sorted for E’s and Wizz’, Pulp’s anthem for disillusioned hedonists, ‘Makes you wonder what it meant.’

For anyone interested in what the Nineties signified beyond the M25, Brooke-Smith’s attempt to sum up the ‘pre-post-everything decade’ is refreshingly ambitious. He finds room for such phenomena as Kurt Cobain, Jeff Koons, the Gulf War, the Y2K bug, Doom and David Koresh (Britpop gets one paragraph). Like Chuck Klosterman’s recent book The Nineties, with which it often overlaps, Accelerate! breaks the decade down into themed essays. Cinema inspires the book’s most delightfully surprising connections, with Brooke-Smith finding links between globalisation and Wong Kar-wai, between Francis Fukuyama and Point Break. He brilliantly ties together The Matrix and You’ve Got Mail, seeing them as ‘relics of an era when it was still possible to see cyberspace and the real world as two separate domains of reality’. But without the chronological propellant that might dramatise the cultural acceleration, this book feels rather too much like an annotated list of stuff that happened. A surplus of hindsight also gets in the way: Brooke-Smith tracks the consequences of the upheavals of the Nineties more effectively than he conveys how it felt to live through them. No retrospective critique of boosterism is more revealing than this 1997 prediction in Wired magazine: ‘We’re facing twenty-five years of prosperity, freedom, and a better environment for the whole world.’ Read it and weep.

If the defining narrative of Nineties culture was the journey from tremendous optimism and underdog creativity to excess and disappointment, then neither book completes the picture: Brooke-Smith downplays the good times while Jones minimises the crash. Still, one can’t help but share Finneas’s yearning for a decade when it was reasonable to feel that today is brilliant and tomorrow will be even better. ‘The sense of possibility in the nineties was really important,’ Steve McQueen tells Jones. ‘It was only a moment, and it didn’t last for long, but it was important all the same.’

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk