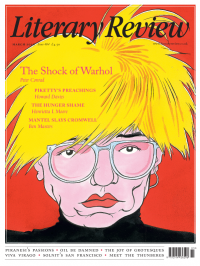

Peter Conrad

Star of the Silkscreen

Warhol: A Life as Art

By Blake Gopnik

Allen Lane 961pp £35

Blake Gopnik’s life of Andy Warhol is less the chronicle of an advance towards death than a protracted postmortem. Gopnik begins halfway through, at what must have seemed to Warhol like the end. In 1968, after being shot by the crazed feminist Valerie Solanas, he was taken in a ‘dead-ish’ state to a New York hospital, where a team of surgeons, awash in his leaking blood as they grappled with his oozing innards, managed to plug the bullet holes and sew his chest back together, leaving Frankensteinian scars that Warhol later showed off to photographers like Richard Avedon.

Placed in a prelude where most biographers would be arranging for their subjects to be born, Gopnik’s almost obscenely vivid account of Warhol’s first ‘death’ – which is how he sees it – overshadows everything that follows. Nine hundred busy pages later, it is balanced by a second demise: in 1987, after an operation to remove his diseased gall bladder, Warhol unexpectedly and perhaps unnecessarily died again, ‘for the second and last time’.

In between, Warhol appears to have been not so much alive as undead. He affected dopey inarticulacy in interviews, envied the automatism of machines and cultivated an affectless ennui as he limoed between parties. Acolytes gave him the vampiric nickname Drella, a compound of Dracula and Cinderella; he was often described as a ghoul or a silver-wigged, acne-pocked angel of death. Richard Burton, who met him at a Rothschild chateau, said he was ‘like a cadaver when still and a failure of plastic surgery when he moved’. Touchingly, Warhol’s diary entry that night was written by naive Cinderella: dazzled by stardom, he noted that Burton was ‘sweet’.

Gopnik humanises the man who pretended to be a monster. In his fey and mother-dominated youth in hard-boiled Pittsburgh, Warhol is actually endearing. He began life in among the murk of the steel mills, where the churches of the eastern European immigrant workers were decorated with holy icons that served as models for his later portraits. He was a self-avowed sissy; his first job was as a shop-window decorator in a local department store, and when he moved to New York he offered himself to advertising agencies as a specialist in drawing female footwear. A college contemporary remembers him as a cuddly bunny, and Gopnik, risking gooiness, repeatedly describes his behaviour as ‘lovely’ and exclaims over the ‘sweet little presents’ he bestowed on friends. What some took to be arrogance was a reflex, Gopnik suggests, of paralysing shyness. Once Warhol’s aloof persona was in place, he claimed not to believe in love, but Gopnik sees in his long trail of failed relationships a thwarted quest for ‘coupledom’. Much depends on whether you can accept that a bad case of anal warts was a symptom of his ardent ‘search for romance’. In one instance, Gopnik resigns himself to uncertainty. In an odd turn of phrase, he wonders whether Warhol was ‘sharing semen’ with a Texan biker, but admits that this remains ‘frankly unknowable’. Ah, the frustrations of biographers, who never get invited into the bedroom!

Gopnik seeks to normalise Warhol by emphasising his work ethic. Despite its orgiastic reputation, the Factory was, he claims, ‘a pretty normal studio’, and Warhol justified his later money-grubbing – especially accepting commissions to produce portraits of socialites, which he mostly contracted out to surrogates, who were kept busy with their silk-screening squeegees in downtown rat-traps – by claiming that he needed to pay his multiple employees. A grateful hanger-on says that it was as if the Statue of Liberty had descended from her plinth to succour not the poor, huddled masses but a random flotsam of drag queens, junkies and misfits. At the end of his life, Warhol even volunteered to serve meals in a church soup kitchen at Christmas. ‘Drella’, Gopnik concludes, ‘was decent all along.’

Yet one of Warhol’s fallen superstars, Viva, thought that he was satanic, and Gopnik finds his ‘passive sadism’ chilling. So how did the flopsy, swishy bunny morph into a night-stalking werewolf? In Gopnik’s long narrative, psychological transitions are covered by snappy aphorisms. Warhol’s successive selves – ‘the elf of 1950s illustration, the imp of 1960s counterculture and the king of 1970s social climbing’ – pass in quick review. A move from painting Coca-Cola bottles to shipping cartons is described alliteratively as a switch ‘from camp to cool’. When success deprives Warhol’s art of its satirical edge, Gopnik observes that by the mid-1960s the art market was beginning ‘to blur the border between Pop and pop’. Later, Warhol the inveterate role-player is capable of nimble reversals: ‘looking more and more like a New Conservative on the surface, deep down he was still an Old Radical.’

Gopnik, an indefatigable researcher, has collected and collated trivia as earnestly as the shopaholic Warhol, whose ‘vast archive’ includes ‘610 Time Capsules and hundreds of other boxes of vital and fascinating records – and junk’. Because he sees Warhol as a conceptualist, Gopnik’s critical task mostly consists of identifying the ‘larger cultural’ phenomena that are ‘the only thing’ that he was ‘any good at painting’. When he has the chance to make aesthetic judgements about Warhol’s ‘anti-aesthetic’ output, he does so with lyrical empathy: in Warhol’s late portraits of his mother, for instance, the ‘frantic strokes’ of paint feel to Gopnik ‘like signs of a scared child’s frantic caresses’. But such occasions are infrequent, because Gopnik believes that Warhol’s life and art were synonymous: like Woody Allen’s infinitely malleable Zelig, he personified the zeitgeist, and the body that Valerie Solanas punctured soon reconstituted itself in the form of ‘Warhol, Inc’.

There are signs that Gopnik, having written so huge a book, needs to inflate Warhol’s achievements to make him worthy of such monumental treatment. His judgements can sound recklessly hyperbolic. Warhol’s co-opting of consumer throwaways like soup cans is said to be his ‘eureka moment – one of the greatest in the history of art’. His painterly rendering of the metal on those disposable containers makes him a master of trompe l’oeil, the ‘most craft-obsessed and conservative of all Western artists’.

Gopnik quotes without comment Norman Mailer’s remark that Warhol’s Kitchen, which documents the ‘mental confusion’ of Edie Sedgwick, was possibly ‘the best film made about the twentieth century’. The tone of that presumably ironic announcement recurs often: when Gopnik says that the sleaze of Blue Movie brought Warhol’s ‘five years as a filmmaker to an (in-?)glorious close’, the parenthetical prefix raises the question of what he actually thinks.

Problems arise when Warhol declares traditional art to be defunct and advances into the realm of ‘postpainting’ or ‘post-art’, where images are not created but manufactured on an assembly line as the consumer economy remorselessly markets its wares. Willem de Kooning accused Warhol of being ‘a killer of art’; Gopnik replies that this was his ‘true, important achievement’. Perhaps so, yet he goes on likening Warhol to the maniacally inventive Picasso, and also to Goya, whose satirical portraits of the Bourbon aristocracy are often invoked to excuse Warhol’s courting of figures like the Shah of Iran as potential customers. Eventually irony gives way to what sounds more like sarcasm when Gopnik compares the ubiquity of Mao’s official portrait in communist China to the proliferation of Warhol’s candy-coloured, depoliticised Maos in the boardrooms and bourgeois houses of the capitalist West.

In a brief epilogue, the book grants the doubly dead Warhol an afterlife, which – perhaps in homage to the assassination attempt in 1968 – consists of bullet points that tabulate the progress of his reputation. Among these is a reference to Warhol’s appearance in a Burger King ad in 2019; then, as a grand finale, Gopnik contends that Warhol now belongs atop Parnassus ‘beside Michelangelo and Rembrandt’. Is he kidding? Worryingly, I have to say that I’m not sure.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk