Patrick Mcguinness

The Death of Doctor Dieu

The Man in the Red Coat

By Julian Barnes

Jonathan Cape 265pp £18.99

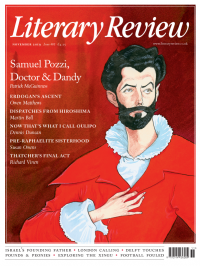

Julian Barnes’s new book immerses us in Belle Epoque Paris through the life of Samuel Pozzi, the sitter in John Singer Sargent’s famous portrait Dr Pozzi at Home. ‘Is it unfair to begin with the coat, rather than the man inside it?’ asks Barnes. ‘But the coat, or rather its depiction, is how we remember him today, if we remember him at all.’ Pozzi is an excellent choice of subject, because he is both straightforward and enigmatic, and because, though he knew everyone and turns up in numerous memoirs, letters and newspaper articles of the period, enough of his character remains just out of reach for Barnes to relish the challenge of imagining him.

This may be why the book’s cover stops just short of showing us Pozzi’s face. What we have instead is the shimmering red coat, tied at the waist, and the sitter’s delicate, long-fingered hands. They are the hands of an artist, though not, as we might speculate from the delicacy and expressiveness of the fingers, those of a pianist or a conductor, a painter or a poet, but of a surgeon. ‘After the picture’s first impact, when we might well think “it’s all about the coat”, we realise that it isn’t. It’s more about the hands,’ writes Barnes, ‘right hand on heart, left hand on loins’, as if to gesture to Pozzi’s amatory prowess, and to his personal, if not always private, life. Sarah Bernhardt, one of the many women he had relationships with, described him as ‘disgustingly handsome’. She first met ‘Docteur Dieu’, as she called him, in 1869. They became lovers and remained friends until Pozzi’s death in 1918. In 1898, Pozzi operated on her to remove an ovarian cyst; in 1915, he arranged the amputation of her leg. In the intervening years, he became one of France’s leading medical practitioners, a pioneering gynaecologist and abdominal surgeon, translator of Darwin, advocate of Listerism, writer, art collector and senator. He established the first chair in gynaecology in France and wrote the gynaecology textbook that remained in use into the 1930s. When he died in June 1918, aged seventy-one, shot by a deranged patient, he was working as a military surgeon, demonstrating the same patriotism he had shown in 1870, when he volunteered as a medic in the Franco-Prussian War. Those dates map uncannily well onto the beginning and end points of the Belle Epoque itself, which was bookended by two French defeats at the hands of the Germans: in the Franco-Prussian War and in the opening months of the First World War.

When Barnes turns his attention to people who actually existed, he is attracted to the parts of them that lie just outside the picture. His Flaubert escapes us at crucial moments. His Shostakovich also eludes us, or suddenly becomes inscrutable, at the very moment we’re most deeply enmeshed in his consciousness. In this book, too, the phrase ‘we cannot know’ recurs, revealing an attractive trait in Barnes’s writing: he is drawn to tact, discretion, scruples. Barnes also approaches the familiar cast of dandies and aesthetes from refreshing angles. One example is the Comte de Montesquiou, who emerges here as touchingly human. Barnes finds that, by dint of being fictionalised by Huysmans, Jean Lorrain and Proust (among others), Montesquiou may have lost some of his own reality. That was the nature of the times, and this is why Pozzi makes such a good subject. He lived in an age of exaggeration, yet here his mattness and sincerity are good foils for the shine and glitter of those in whose circles he moved – Bernhardt, Réjane, Wilde, Lorrain, Sargent, Whistler and countless others.

Pozzi was born in 1846 of Italian Protestant parentage. A brilliant medical student, he was also cosmopolitan. In 1876 he went to Scotland to meet Joseph Lister, whose antiseptic methods he supported, and thereafter travelled widely to learn about medicine. This is an important detail: Barnes approvingly quotes Pozzi’s maxim ‘Chauvinism is one of the forms of ignorance’, and in his afterword relates this to Brexit and to the illusions of national exceptionalism. Despite the Debussys and Zolas, the Colettes and the Judith Gautiers, the Belle Epoque in France wasn’t just a time of artistic and scientific advances, broad-mindedness and relaxed morals. It was, as this book reminds us, a period of nationalism and anti-Semitism, of revanchism and militarist sabre-rattling. For every Wilde lobbing risky bons mots across the dinner table, there was another writer demanding war against Germany or the expulsion of Jews and Protestants. Barnes loves France and is fascinated by the Belle Epoque, but he doesn’t idealise it, and reading this I found myself thinking how the period I’ve studied as an academic, at one or more historical removes from the present, has something to tell us about the world we live in now: the difficulty of nailing lies, stopping rumours and cleaning public discourse in a world saturated by spectacle. Flaubert, whom Barnes knows better than most, saw the 19th century as a period dazzled by the myth of progress, and Flaubert returns a few times here, not least with his great dictum ‘You cannot change people; only know them.’

If the best the writer can hope for is to know people, the doctor at least has the chance of curing them. But being a doctor in the Belle Epoque was a dangerous business. Doctors were often attacked by their patients; Barnes recounts several cases here, including one in which Gilles de la Tourette, of the syndrome that bears his name, was shot three times by a patient claiming hypnosis had made her unable to work. Tourette survived, but Pozzi was not so fortunate. In 1915, in the midst of war, he inexplicably agreed to operate on the scrotum of a minor civil servant called Maurice Machu. Why? ‘We cannot know’, but Barnes nevertheless speculates: ‘perhaps the notion that, in the middle of mass European carnage, a man might worry about his scrotum appealed to his sense of the absurd. Or perhaps it was simpler: here, at least, is something I can fix.’

On 18 June 1918, after a day of operating and visiting patients in a military hospital, Pozzi returned home to find Machu accusing the doctor of rendering him impotent. Machu shot him three times, then shot himself in the head. Pozzi was conscious enough to specify what sort of operation and anaesthetic he wanted, but died later that day.

For all his tactile skills and his good looks, his distinctions and his success with women, Pozzi emerges in this book as grounded, empathetic and a little melancholy. His love life was both variegated and sad: a stream of affairs eddying around an unhappy marriage, and a mistress he was unable to marry because his wife refused him a divorce. Perhaps the most compelling voice in this book is that of his brilliant daughter, Catherine Pozzi, later to become a poet and the author of a powerful autobiographical novella, Agnès. Precocious, miserable, painfully and self-torturingly observant, in her diary Catherine offers a dark counterpoint to the shiny surface of Pozzi’s life, mercilessly depicting her unhappy parents and the damage they inflict on their children.

Many countries have had periods of prosperity, artistic achievement and technological advance; of wealth, decadence and drama. But there is only one Belle Epoque. This gracefully written and generously illustrated book is also deeply researched. An absorbing work of biography and cultural history, it has plenty to say, indirectly but firmly, about an époque rather closer in time.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk