Munro Price

Vichy’s Long Shadow

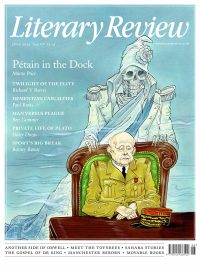

France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain

By Julian Jackson

Allen Lane 480pp £25

On 23 July 1945 the 89-year-old Marshal Philippe Pétain, until recently head of the French state, went on trial for his life before a specially convened High Court in Paris, accused of attacking national security and collusion with Nazi Germany amounting to treason. For four years, from the fall of France to the liberation, he had steered the Vichy regime created from the wreckage of defeat into collaboration with the new continental hegemon, Adolf Hitler. Now, after eight months of wandering to escape the advancing Allies through eastern France to the castle of Sigmaringen in Germany and finally to Switzerland, he was in the custody of General de Gaulle’s provisional government.

Pétain’s trial was about much more than the fate of one extremely elderly man. It was newly liberated France’s first opportunity to confront the traumas it had endured from May 1940 to August 1944: the catastrophic military defeat by Germany, the signing of the armistice, the dissolution of the Third Republic and its replacement by the authoritarian Vichy state, the deportations of Jews and the increasingly bloody civil war between the collaborationist regime and the Resistance. In his splendid book, Julian Jackson does justice to all these aspects. The central narrative of the trial grips like a thriller and the history of Vichy itself, which inevitably involves much retrospective explanation, is seamlessly woven into it without ever slowing the story’s momentum. Jackson’s vivid prose is leavened by wit and sharpened by telling details, often drawn from his rich knowledge of the French culture of the period, ranging from Les Enfants du Paradis to the writings of Céline. This is a substantial achievement by a historian at the top of his game.

At the heart of the book is the enigmatic figure of Pétain himself, one of the great French heroes of the First World War, the defender of Verdun. His prestige and the popular confidence he inspired as French forces collapsed before the German Blitzkrieg were crucial to establishing the Vichy regime. The son of a peasant, he had a calm, grandfatherly presence and carefully cultivated his image as the embodiment of unchanging rural France, which underwrote the legitimacy that Vichy enjoyed. Whether, or to what extent, he became senile over the four years following the establishment of the Vichy government remains a controversial issue. He barely spoke at his trial, sometimes appeared confused and made great play of his deafness, yet these handicaps miraculously disappeared at key moments in the proceedings. His brutal disavowal of his old comrade-in-arms, the blind General Lannurien, who stumbled in his testimony for the defence, is a case in point. As Jackson pithily puts it, ‘Pétain was never shy of ditching his most devoted followers if necessary.’

Whereas Pétain remains enigmatic, the extraordinary qualities of his nemesis, de Gaulle, stand out very clearly in the book. One of the fascinating facts Jackson brings to our attention is that the rivalry between the two men began as a literary quarrel. In the 1930s de Gaulle, who had been ghostwriting a history of the French army for Pétain, completed and published it under his own name after the marshal had abandoned it, in spite of Pétain’s objections. De Gaulle’s devastating comment on Pétain in his memoir, ‘Old age is a shipwreck’, is famous, but Jackson also quotes some remarkable notes he wrote about Pétain as early as 1938: ‘Too ambitious to be a mere arriviste … Too prudent not to take risks … His philosophy is one of adjustment … More grandeur than virtue.’ Behind the splendid aphorisms, de Gaulle’s prescience was uncanny.

The trial itself was a riveting, often chaotic, spectacle. It was held in the Palais de Justice on the Ile de la Cité, once the principal residence of the French kings. Into the small courtroom were crammed magistrates, witnesses, journalists. The photographers sometimes had to crouch at Pétain’s feet to take their pictures. Beneath the surface, however, lurked the ambiguities and contradictions that are inevitable when a new regime puts its predecessor on trial. The presiding judge, Mongibeaux, like almost all his colleagues, had previously sworn an oath of loyalty to the marshal, while the jury pool was carefully limited to prewar parliamentarians and members of the Resistance. The court procedure barely masked the fissures in French society opened up over the previous four years.

Jackson not only uses Pétain’s trial to analyse the greatest disaster of 20th-century France; he also sheds light on older traumas of modern French history. In particular, he evokes the long shadow cast over the trial by the French Revolution, which seems to have been omnipresent in observers’ minds. Describing the packed balcony from which spectators craned their necks to get a better view of the court below, one journalist wrote, ‘all that is missing are the Phrygian caps of the Revolutionary tribunals.’ Pétain’s trial was constantly compared to that of Louis XVI in 1792. For his supporters, it was, like Louis’s, a travesty of justice; for his enemies, it was, again like Louis’s, the legitimate trial of a head of state for treason. Since speaking directly about Pétain was too controversial, when the marshal’s most eloquent defender, Maître Isorni, later became a star of the French lecture circuit, he instead gave lectures about the king’s trial (which the audience often punctuated with cries of ‘Long live Pétain!’).

A striking element of the trial was the prosecutors’ obsession not with Pétain’s actions in power but with chasing the will-o’-the-wisp of whether the Vichy state was the culmination of a deep-laid plot against the Third Republic stretching back through the 1930s. This was highly unlikely, and unprovable anyway. However, as Jackson underlines, the question formed the longest section of the act of accusation against Pétain, and the public prosecutor spent the first two hours of his closing speech on it. This preoccupation with plots will be familiar to any student of the French Revolution, and it resurfaced at intervals throughout France’s 19th-century upheavals. Its reappearance at the Pétain trial was disturbing.

If the Pétain trial had a prehistory, has it left a legacy? In the short term, it resolved the problem of what Pétain’s fate should be: he was condemned to death, though this sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment on an island off the coast of western France, where he died in 1951. In the longer term, the trial was intended to condemn Vichy France itself and its extreme right-wing ideology of authoritarianism, exclusive nationalism and racism. Here it did not entirely succeed. Official France, of course, continues to repudiate the Vichy state as an illegal regime born of military defeat. Yet there are signs today that the ‘Vichy taboo’ may be lifting. The most obvious evidence is the candidature of the extreme nationalist Eric Zemmour in the 2022 presidential election. During his campaign, Zemmour openly defended Vichy as having shielded France from Hitler’s worst excesses – a standard right-wing argument, though bizarre coming from a public figure who is himself Jewish. This makes more sense, however, in the light of Zemmour’s wider aim, which is to use the kinds of measures the Vichy government applied to Jews as a weapon against France’s Muslim community. He has advocated extensive denaturalisation of French Muslims and the eradication as far as possible of Islam as a religion in France.

In the event, after a strong start Zemmour came only fourth in the first round of the presidential election, eclipsed by the more established candidate of the far right, Marine Le Pen. For Jackson, this shows that although the far right remains powerful in France, the ghost of Vichy has been banished. This reviewer is more pessimistic. Le Pen’s policies on immigration and Islam are only marginally less radical than Zemmour’s, and for all her attempts to detoxify her party, the Rassemblement National, few of its supporters are unaware of the fact that its founder, her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, has both defended Vichy and downplayed the Holocaust. If Marine Le Pen wins the next presidential election in 2027, which is by no means impossible given Emmanuel Macron’s current unpopularity, France will face her greatest challenge since June 1940.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Literary Review is seeking an editorial intern.

Though Jean-Michel Basquiat was a sensation in his lifetime, it was thirty years after his death that one of his pieces fetched a record price of $110.5 million.

Stephen Smith explores the artist's starry afterlife.

Stephen Smith - Paint Fast, Die Young

Stephen Smith: Paint Fast, Die Young - Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon by Doug Woodham

literaryreview.co.uk

15th-century news transmission was a slow business, reliant on horses and ships. As the centuries passed, though, mass newspapers and faster transport sped things up.

John Adamson examines how this evolution changed Europe.

John Adamson - Hold the Front Page

John Adamson: Hold the Front Page - The Great Exchange: Making the News in Early Modern Europe by Joad Raymond Wren

literaryreview.co.uk