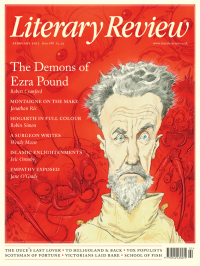

Robert Crawford

Voice from the Asylum

The Bughouse: The Poetry, Politics and Madness of Ezra Pound

By Daniel Swift

Harvill Secker 299pp £25

Among the bombings that marked the beginning of 2017, one took place on New Year’s Day at the CasaPound bookshop in Florence, an outpost of the Italian neo-fascist or ‘alt-right’ CasaPound movement, which takes its name and inspiration from the American poet Ezra Pound. As Daniel Swift points out in the ‘CasaPound’ chapter of The Bughouse, in December 2011 ‘a CasaPound supporter went on a shooting spree in a market in Florence and killed two Senegalese traders and wounded three more’. He also notes links between Pound and the American neo-fascist and white supremacist John Kasper, suspected of orchestrating the bombing of a high school. On trial in Florida, Kasper, a disciple of Pound who visited the poet regularly, ‘held a copy of Mein Kampf in one hand’.

Swift’s book does not draw connections between Pound and American ‘alt-right’ campaigners of our own day, but it might be easy to do so. An article on the ‘alt-right’ website Radix, dated 31 December 2016, begins, ‘The United States is a sick place. In 1958, famous poet Ezra Pound once noted that “America is an insane asylum,” and those words seem truer today than they did back then.’ The writer of the article appears to be a supporter of Donald Trump.

Examining some of Pound’s late prose writings, Swift concludes that ‘Pound never calls for violence, but preaches brutality in code.’ His book concentrates on the period, between 1945 and 1958, when Pound was incarcerated in the huge Washington mental hospital of St Elizabeths – which Pound nicknamed ‘the bughouse’ – after his legal team had successfully argued that he could not be tried for treason because he was insane. Before joining about seven thousand other inmates at St Elizabeths, Pound had been detained in Guantanamo-like conditions in a prison camp near Pisa controlled by US forces. The crime he was accused of was making, throughout the Second World War, radio broadcasts for Mussolini in an attempt to convince Americans of, among other things, the rightness of the Fascist cause. For Pound, America’s modern political leaders had abandoned true American values; he considered Hitler to be a martyr, Churchill a supporter of ‘kikes’ and Mussolini a great ‘Boss’.

Pound was lucky not to be executed as a traitor. The defence of insanity saved him but also condemned him. From the asylum he submitted for publication his Pisan Cantos, which was soon awarded one of America’s most prestigious literary awards, the Bollingen Prize. This is a reminder, if one were needed, that he continued to be regarded as one of the 20th century’s leading English-language poets. He had, after all, been at the heart of the Imagist movement; he had also produced, in Cathay (1915), perhaps the greatest volume of verse translations in English and, Swift asserts, ‘arguably the book which invents modernist poetry’; his friend T S Eliot had described him as il miglior fabbro (‘the greater craftsman’) after Pound helped edit The Waste Land; his ongoing Cantos, an epic of Coleridgean and Ossianic ambition, ranked among the most provocative achievements in the poetry of the Anglophone avant-garde. At the heart of Swift’s book is the issue of how Pound could be at once Fascist, madman and great poet.

Although it ranges across many aspects of Pound’s career, covering territory familiar from earlier biographical studies, The Bughouse operates as a stylish and rather sketchy group biography, focusing on Pound’s most distinguished visitors at St Elizabeths. These included Elizabeth Bishop, Charles Olson, William Carlos Williams, T S Eliot, John Berryman, Robert Lowell and Frederick Seidel. Several of these poets were familiar with mental illness. Eliot, for instance, had experienced nervous breakdown and knew what it meant to live with a partner who suffered from hallucinations; Lowell spent significant periods in psychiatric hospitals. Although he lacks the psychiatric training and unfettered access to medical records enjoyed by Kay Redfield Jamison (whose new book, Robert Lowell: Setting the River on Fire, is a work of remarkable insight), Swift has trawled publicly available records of St Elizabeths and treats Pound’s stay there with eloquence as well as understanding.

Swift’s strength is his refusal to separate Pound’s writings from the issues of Fascism and insanity. Controversially, Swift sees Pound’s Section: Rock Drill cantos (published after the Pisan Cantos) as ‘a document of madness’, bound up with conspiracy theories about ‘history’s hidden schemes’, among them the notion that ‘the British involvement in the Second World War was motivated by a quasi-racist plot, devised by Churchill, to kill Germans’. Pound was convinced that poetry could be used as a sensitive instrument to discern and articulate patterns within history. He sought in the Cantos to write an epic poem that would contain and interpret history (including American, European, Chinese and other histories) for the benefit of mankind. Yet the megalomaniac nature of this project – a sort of versified globalisation – was bound up with what one of the doctors who examined him called ‘delusions of persecution and grandeur’.

Sometimes Swift, whose prose is winningly jargon-free, sharp-eyed and pacey, indulges himself too much in repeating motifs: on page 38, for example, Charles Olson ‘notes how Pound worries at the frayed cuffs of his shirt’, and on page 49, Olson ‘records that at their first meeting Pound worried at his shirt cuff’. Sharper editing would have combed this out. Occasionally Swift’s style has notes of Paterian ambition. He mixes group biography with travelogue, literary criticism and political analysis, restlessly refusing to commit to any single genre. Among the Pound critics whom Swift admires is Hugh Kenner, whose combination of encyclopaedic sweep and glancing analysis can be both enthralling and frustrating. Although Swift’s aperçus are striking, he glissades too speedily from topic to topic, refusing to spend long on any one of Pound’s connections with the poets and family members with whom he had relationships during his incarceration, or on Pound’s present-day legacies. Sometimes he strives too hard for journalistic impact: ‘Ezra Pound was the most difficult man of the twentieth century.’ A university-level teacher of literature who is commendably uneasy about academic and mental ‘institutions’, Swift at other times pulls his punches. Of ‘the Ezra Pound International Conference, known affectionately as EPIC’, he says simply, ‘I hear no mention of fascism or anti-Semitism.’ Although conscious of ‘the scholarly dreamworld’, Swift seems loath to disrupt it too much. When he writes that ‘Pound scholars are like a family; and his family are scholars’, this sounds both too cosy and too cultish.

Still, Swift is a sensitive, alert reader of poetry and pictures. He knows Pound’s work thoroughly and manages to communicate to his readers many of its lyrical and adventurous attractions. He says too little about religion, about the messianic Pound’s relationships with his wife, lovers and children, and about links between poetry and madness, the origins of which lie much earlier than the Romantic era. Academics may complain that nowhere in this study of madness, punishment and incarceration is there any invocation of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. Anecdote and story, rather than theory-driven analysis, are what power this book. Pound scholars will find little in it that is revelatory, but for poets, students and general readers it highlights memorably the tangled relations between lunatic, lover and poet.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Under its longest-serving editor, Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair was that rare thing – a New York society magazine that published serious journalism.

@PeterPeteryork looks at what Carter got right.

Peter York - Deluxe Editions

Peter York: Deluxe Editions - When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines by Graydon Carter

literaryreview.co.uk

Henry James returned to America in 1904 with three objectives: to see his brother William, to deliver a series of lectures on Balzac, and to gather material for a pair of books about modern America.

Peter Rose follows James out west.

Peter Rose - The Restless Analyst

Peter Rose: The Restless Analyst - Henry James Comes Home: Rediscovering America in the Gilded Age by Peter Brooks...

literaryreview.co.uk

Vladimir Putin served his apprenticeship in the KGB toward the end of the Cold War, a period during which Western societies were infiltrated by so-called 'illegals'.

Piers Brendon examines how the culture of Soviet spycraft shaped his thinking.

Piers Brendon - Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll

Piers Brendon: Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll - The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West by Shaun Walker

literaryreview.co.uk