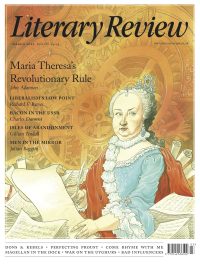

John Adamson

Holy Roman Administrator

Maria Theresa: The Habsburg Empress in Her Time

By Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger (Translated from German by Robert Savage)

Princeton University Press 1,104pp £35

Empress Maria Theresa is a small and distant figure in British historical memory. Insofar as she figures at all, it is probably as the Austrian monarch in whose reign Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal set their operatic hit of 1911, Der Rosenkavalier, that nostalgic evocation of an idealised Habsburg ancien régime, all rococo curlicues, powdered wigs and schmaltz.

In the German-speaking world, however, and especially in Austria, the core of the vast agglomeration of lands she ruled from 1740 to 1780, Maria Theresa remains a towering figure: the war leader who took on her nation’s would-be invaders and won; the beneficent and lovable ‘mother of the nation’; the reformer of government and civil service who laid the foundations of the modern Austrian nation-state. Imagine Elizabeth I, the late Queen Mother and Mrs Thatcher all rolled into one and you have some idea of her place in national myth.

Yet even in an age when studies of history’s powerful women are very much in vogue, biographies of Maria Theresa in English are rarities; works based on serious archival scholarship rarer still. All of which makes this impressive new biography the more welcome. Its author, Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger, is the rector of the prestigious Berlin Institute for Advanced Study – a sort of Germanic All Souls – and has been researching and thinking about the 18th- and 19th-century Habsburg world for the best part of four decades. And in these clever and coruscating pages, it shows.

First published in German in 2017 to mark the tercentenary of Maria Theresa’s birth, this biography offers insight and erudition on a massive scale: some eight hundred pages of text and a further two hundred of notes and references. But if that sounds daunting, breathe easy: her book is a work not only of prodigious learning, but also, in this elegant English translation by Robert Savage, of page-turning readability that transports its reader to a distant and endlessly fascinating world.

It is also very much more than just a biography. Yes, the arc of Maria Theresa’s life is there, from cradle to grave, but it is also minutely contextualised in a series of thematically focused chapters, exploring such topics as her religious life, court, family, government, empire and the impact of Enlightenment thought. What emerges is a richly multi-dimensional portrait of her rapidly changing age, a period when Habsburg power, which had once spanned the globe, was in retreat, when the dynasty’s dominance within the Holy Roman Empire was being challenged by Frederick the Great’s upstart Prussia and when the ideas of the philosophes were calling into question the very basis of the Habsburgs’ belief in their divinely conferred mandate for rule.

If that sounds as though her reign was all about ‘managed decline’, there was a time in the early decades of the 18th century when it seemed unlikely there would be any Habsburg decline to manage. The Spanish Habsburgs had become extinct in the male line in 1700, triggering a major European war over the succession. The Austrian Habsburgs similarly reached the end of the road not long after. The sonless Charles VI became Holy Roman Emperor in 1711, and upon his death a similar carve-up was expected of the huge swathe of territories he ruled, which included Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Croatia and much of northern Italy.

Although Charles VI obtained an international agreement to the highly unusual (and in the Habsburg context almost unprecedented) expedient that his daughter Maria Theresa, born in 1717, should be recognised as the heir to his Austrian lands, many of the key signatories reneged on their pledges. The emperor’s death in 1740 triggered yet another Habsburg war of succession as neighbouring states, Bavaria and Prussia in the vanguard, swooped to deprive Maria Theresa of

her inheritance.

In the ensuing War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48), Maria Theresa, though still in her twenties, displayed a combination of personal courage, political guile and strategic skill that repeatedly wrong-footed her opponents. By the end of the decade, she had successfully reasserted her authority throughout the ancestral Habsburg domains, albeit with the loss of the rich province of Silesia to Prussia. Debarred as a result of her sex from following her father as Holy Roman Emperor, she arranged the next-best thing: the election of her uxorious and generally obedient husband, Francis, Duke of Lorraine, in 1745, to the prestigious, if increasingly marginalised, imperial throne. Her own title of empress was enjoyed not as sovereign but merely as consort to the emperor.

***

Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor.

This four-decades-long female ascendancy was sustained, Stollberg-Rilinger shows, thanks to Maria Theresa’s high intelligence, her talent for choosing loyal and able ministers, and above all a seemingly boundless capacity for work. The War of the Austrian Succession had exposed the inefficiencies of the ancient system she had inherited, in which decision-making and power over finances were dissipated among a host of regional assemblies and feudal lords.

Centralisation therefore became the defining policy of the reign, cutting through the tangle of local rights and jurisdictions and concentrating decision-making power in the key areas of finance, justice and military affairs in the hands of the monarch. This was something more than a simple power grab by a would-be absolutist monarch. Influenced by Enlightenment analogies between the well-ordered state and a large and well-modulated clock, Maria Theresa and her reformist advisers set about creating a mechanism through which the wise initiatives taken at the centre – in the Hofburg in Vienna or in Maria Theresa’s new summer palace of Schönbrunn just outside – could set in motion a benign ‘chain reaction that would reach all the way to the outermost cogs of the state’.

This clockwork state was also the ultimate nanny state. The regime’s ambition, Stollberg-Rilinger argues, was the creation of an ‘all-encompassing system of [state] control’, in which a benignly bossy matriarch issued edicts to improve her subjects’ health (Maria Theresa was an early champion of vaccination), morals (she sought to limit masked balls to constrain the immorality associated with anonymous gatherings) and education (her government introduced a new schooling system that required the attendance of all children between the ages of six and twelve).

There were, however, large areas of policy where Maria Theresa remained impervious to Enlightenment thought. Devout in her Catholic faith, which she regarded as a mainstay of the monarchy’s own ‘sacred mission’, she hated Protestants and Jews and initiated selective expulsions of both. The freedom of expression so prized by the philosophes was equally antithetical to her outlook. She imposed strict censorship to suppress public criticism of her regime, surreptitiously monitoring correspondence to seek out seditious views. The criminal code retained its full repertory of gruesome punishments, and even her belated decision to abolish torture (in 1776, just four years before her death) was made against her better judgement. She opposed the move, she admitted privately, ‘since I am no lover of innovation’.

Few felt the oppression of matriarchal control more than her children – eleven daughters and four spare sons besides her heir. These became pawns in an international chess game, with Maria Theresa seeking influence in foreign courts by inserting her progeny as wives or husbands within the great ruling dynasties of Europe. Maria Theresa’s ill-starred daughter Maria Antonia – ‘Marie Antoinette’ as she was to be known in France – was merely one victim of her mother’s diplomatic ambitions.

Maria Theresa’s new state-clockwork, Stollberg-Rilinger insists, produced its own peculiar contradictions. The new cohorts of civil servants her government employed, recruited for their abilities rather than their pedigrees, enabled the government to monitor its subjects’ lives more intrusively than ever before, and paperwork increased exponentially. During the fifty years from 1748, the Habsburg civil service produced three times as many documents as it had during the preceding two centuries. With all major questions requiring the personal input of the empress for their resolution, the huge inflow of memoranda and briefing papers frequently came close to swamping the decision-making system it was intended to improve.

‘To celebrate Maria Theresa as the founder of the modern state’, writes Stollberg-Rilinger, ‘is to confuse the reformers’ rationalist fantasies with reality.’ The belief that governmental problems could be solved by ‘constant tinkering’ with the central machine of state proved illusory. The business of reform needed to ‘start at the local level’, among peoples whom the bureaucrats in Vienna barely understood.

In the last years of her reign, as Stollberg-Rilinger shows, Maria Theresa cut a melancholy if still indefatigable figure, struggling to comprehend the social and intellectual currents that were transforming the world around her, appalled by the spread of the ‘brazen idea that people can and should have the courage to use their own reason’, yet sufficiently self-aware, as she toiled on her papers to the last, to know that it was she who was out of step with the world.

No biography is ever definitive. But this one is set to be the basic reference point for studies of Maria Theresa for decades to come. Its integration of her life and times raises the bar of the biographer’s craft, revealing just how profoundly the world of 18th-century central Europe was moulded – if never to the full extent of her ambitions – by that relative rarity in the council chambers of pre-modern Europe: a politically powerful woman.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk