John Adamson

Boudoirs & Barricades

The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748–1789

By Robert Darnton

Allen Lane 576pp £35

Louis XV had a problem with Paris. Until the late 1740s, he had regularly visited the capital on his way from Versailles to his favourite hunting grounds in the forest of Compiègne. But over the winter of 1749–50 there was a series of kidnappings of street urchins in Paris. By the spring of 1750, rumours were circulating that the capital’s police were complicit in the abductions. By May, lurid stories were doing the rounds that the abducted children were being bled to death so that a member of the royal family with leprosy could bathe in their blood, which was supposedly therapeutic. Riots ensued – one involving a crowd ten thousand strong. Order was restored by the deployment of soldiers and the public hanging of three of the ringleaders in the Place de Grève. But Louis XV thereafter avoided Paris on his regular journeys to Compiègne. He would not expose himself to his Parisian subjects, he declared, because they had called him ‘a Herod’ – another king with a tricky reputation when it came to matters of child welfare.

That problematical royal relationship with Paris forms the central theme of this highly enjoyable new book, an attempt to gauge the capital’s ‘temper’ in the four decades before the fall of the Bastille in 1789 – that moment when the surviving children of 1750, now strapping citizen-soldiers, rose in rebellion to capture the fortress in the east of the city that had come to symbolise the despotism of Bourbon rule.

‘Temper’, of course, is an elusive thing to define. To Robert Darnton, it is a set of overlapping types of shared consciousness: a composite of ‘collective memory’ informed by decades of gossip, rumour and news. Calibrating such a phenomenon is difficult enough in an age of market research and opinion polls. Gauging it for the largest city in continental Europe in the 18th century (Paris had a population over 600,000 by the 1770s), with far more limited evidence to go on, could easily become a quest for the unknowable.

Darnton, however, is no ordinary historian. A former occupant of prestigious chairs at Princeton and Harvard, he is probably the USA’s most garlanded scholar of 18th-century France. He has been studying how Parisians acquired their news for the best part of six decades. Now in his ninth decade, he somehow combines acuity and erudition with an unbounded zest for literary performance. His energy seems palpable on every page.

Darnton addresses the slipperiness of his subject at the outset. With a deferential nod to the anthropologist Clifford Geertz, he argues that analysing collective experience is not ‘an experimental science in search of law but an interpretative one in search of meaning’. By scrutinising a series of major events during the four decades before the French Revolution and teasing out ‘how people made sense of [those] happenings’, one can discern the ‘emergence of a revolutionary temper’ – the source of so much of the combustibility of 1789 – and trace its development across time.

Darnton chooses forty or so ‘happenings’ from the four decades before the French Revolution, each crisply recounted in chapters that rarely run to more than ten pages, and assesses what Parisians made of them. All the period’s great political événements are here: Louis XV’s calamitous foreign wars and the humiliating treaties that ended them; the repeated clashes between royal government and the Paris Parlement (the city’s hugely prestigious high court); the summoning of the Estates General and the fall of the Bastille. So too are the great cultural events of the age: we have the publication of Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, Rousseau’s Emile and Voltaire’s Traité sur la tolerance (his plea for religious toleration), along with the performance of Beaumarchais’s hierarchy-subverting Mariage de Figaro – the great succès de scandale of the 1770s Parisian stage – and much else. Even the first public balloon flight over Paris in 1783, emphasising the boundless possibilities of science, finds its place on Darnton’s list.

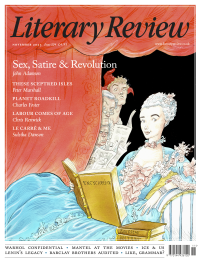

Scandal also figures in more destructive forms: the ‘depredations’ of the royal treasury by the royal mistresses Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry; royal ministers with their hands in the till; skulduggery on the stock market; and the most labyrinthine scandal of them all, the Diamond Necklace Affair – the murky imbroglio of the 1780s that damningly associated Marie Antoinette with a greed for jewels, midnight trysts with a cardinal and an Italian necromancer who claimed to have attended the wedding feast at Cana.

In hands less adroit than Darnton’s, such a catalogue of events, all of them well known to historians, might have amounted to no more than a compilation of the ancien régime’s greatest hits. Where his book has something genuinely new to offer, however, is in delineating the conduits through which information about each of these various episodes came to lodge in the consciousness of Parisians. These conduits were numerous, ranging from smuggled French-language newspapers printed abroad to manuscript newssheets, gossip, graffiti and ribald songs.

The audience for such information was also exceptionally wide. The majority of adult Parisian males were literate by the mid-18th century, but the semi-literate could also take in texts aurally, as topical and even contraband material was often read aloud in cafes or at open-air meeting spots such as the Jardin du Luxembourg and the garden of the Palais-Royal.

The view of the royal court that was retailed was rarely a complimentary one. For purveyors of news of governmental incompetence and corruption, Versailles was the gift that kept on giving. Whether it was claims in the 1740s that Madame de Pompadour had infected the libidinous Louis XV with venereal disease or reports in the 1780s that Marie Antoinette had cuckolded the virtuous Louis XVI with lovers of both sexes, the Versailles court provided a regular drip-feed of sexual scandal that seeped ever deeper, Darnton argues, into the awareness of Parisians, permanently colouring their view of both the monarchy and the political elite.

The great controversies in the worlds of philosophy and political theory also found their way into the gazettes and discussions of the metropolis. Very few Parisians ever encountered directly one of the Enlightenment’s greatest achievements, the Encyclopédie, the noble venture to comprehend all human knowledge published in seventeen folio volumes between 1751 and 1765 (at 980 livres, the price of the first edition was not far off a lifetime’s wages for a common labourer). Fewer still got to see how the Encyclopédie’s diagrammatic ‘Tree of Knowledge’, which provocatively bracketed ‘Revealed Theology’ – the core business of the Catholic Church – with ‘Black Magic’ and other forms of ‘Superstition’.

Yet ordinary Parisians came to know the Encyclopédie’s key arguments, as they would those of Rousseau’s The Social Contract, published in 1762, through the authorities’ heavy-handed efforts to suppress them. In 1752, the royal Conseil d’Etat condemned the Encyclopédie’s first two volumes as containing ‘several maxims that tend to destroy royal authority’ and ‘establish a spirit of independence and revolt’. Works anathematised by the archbishop of Paris or condemned by the Paris Parlement to burning by the public executioner acquired a currency in the cafes and salons of the metropolis that would have been unobtainable without the publicity gold of official censure.

*

How did all of this Parisian temper-raising contribute to the outbreak of the revolution? Although Darnton is at pains to stress that there was no ‘clear line of causality’ between the two, his book often manages to leave the impression that there was. Almost every one of his chapters ends with an observation on how the event just described worked to enhance discontent, undermine orthodoxies or insinuate ‘questions about the legitimacy of the political system’. The effects, he implies, were steadily cumulative, finally producing the ‘revolutionary temper’ that inspired the assault on the Bastille. This tendency to illuminate the events of 1748 to 1788 by means of the backwards glow of 1789 curiously narrows the field of view. Thus illuminated, the ‘meaning’ that comes to light in each case is almost invariably an anti-regime one. The possibility that these same events could have multiple, sometimes very different meanings for contemporaries is rarely considered. Moreover, a crowd’s powers of forgetting could be just as strong as its powers of recall. In a major political crisis, as Colin Jones’s recent book on Paris during the fall of Robespierre has revealed, it was often the latest events that bulked largest in the collective consciousness.

Such quibbles apart, this book succeeds impressively as a portrait of one of Europe’s earliest and most sophisticated ‘information societies’. It is hard to imagine a more engaging introduction to the intellectual currents of 18th-century France or to the paradoxical metropolis – simultaneously palatial and squalid, the city of Sèvres porcelain and of breaking on the wheel – where they eddied and converged.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

Give the gift that lasts all year with a subscription to Literary Review. Save up to 35% on the cover price when you visit us at https://literaryreview.co.uk/subscribe and enter the code 'XMAS24'