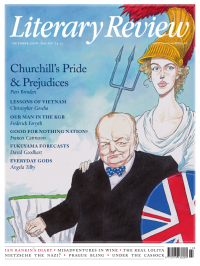

Piers Brendon

Cometh the Hour

Churchill: Walking with Destiny

By Andrew Roberts

Allen Lane 1,152pp £30

Churchill: The Statesman as Artist

By David Cannadine (ed)

Bloomsbury 172pp £25

The easy way to write a full-scale life of Winston Churchill is to quarry material from the official biography, eight huge tomes completed by Martin Gilbert and accompanied by documentary volumes that continue to thud from the presses. This was the procedure adopted by Roy Jenkins, who never visited the Churchill Archives Centre, where his subject’s papers are stored in 2,500 boxes, and composed a flatulent summary of Gilbert that was absurdly over-praised by the critics. The more difficult way to resurrect Churchill between hard covers is to discover new sources by delving into repositories near and far, and to pen an original portrait of an all-too-familiar figure. This is Andrew Roberts’s method and he uses it to excellent effect. Churchill: Walking with Destiny is the best book he has written since his prize-winning biography of Lord Salisbury.

To be sure, the fresh details that Roberts has unearthed scarcely change the big picture. He claims, for example, that George VI’s unexpurgated diary, one of the ‘last pieces in the archival jigsaw’, has helped him to present Churchill in his true colours. Yet the entries he quotes are almost inconceivably banal. On 18 May 1940, as German panzers were scything through France, the king recorded lamely, ‘The situation was serious, and [Winston] is afraid that some of the French troops had not fought as well as they might have done.’ The truth is that George VI, an old appeaser who resented Churchill’s support for Edward VIII during the abdication crisis and his pre-eminence during the war, was, as Lloyd George said, ‘a nitwit’. Roberts himself, in Eminent Churchillians, cited George VI’s official biographer, Sir John Wheeler-Bennett, who could find no evidence that the king ‘exercised any influence or ever thought about anything’.

In fact, Roberts tends to offer the conventional view of Churchill, namely that he was guilty of ‘catastrophic errors’ throughout his career, but that these were more than offset by his correct assessment of the Nazi danger, his sublime resolution in 1940 and his incomparable wartime leadership. The list of mistakes, which enabled critics plausibly to assert that Churchill had genius without judgement, is formidable: opposition to women’s suffrage, sending untrained forces to Antwerp in 1914, initiating and sustaining the Gallipoli expedition, attempting to crush Bolshevism at birth, backing the Black and Tans in Ireland, taking Britain off the gold standard and opposing Indian independence. What is more, the blunders continued during the Second World War. The Norwegian campaign was a fiasco. Churchill underestimated the Japanese, dismissing them as ‘the wops of the Far East’. The invasion of Italy showed how wrong he was about Europe’s ‘soft underbelly’. Churchill was fallible on weaponry, logistics and even strategy. His relentless advocacy of amphibious operations in irrelevant theatres of conflict, from Scandinavia to Sumatra, seriously hampered the war effort.

All this and much more Roberts acknowledges. So plainly his book is not a hagiography; rather it is a cogent and plausible tribute. Thus Roberts points out that, as a Liberal minister, Churchill championed social reform and enlightened attitudes towards criminals – their treatment was a test of civilisation, he said, and (unlike Chris Grayling) he thought it essential to provide them with books. Churchill ensured that the fleet was ready for battle in 1914. He understood the importance of cryptography better than anyone in Westminster. Although fascinated by war, he favoured peace where possible. Roberts is surprised that he tried to end the Cold War by appeasing the Russians, yet he had previously adopted a conciliatory approach towards the Boers, the Irish, the Turks, the Japanese, strikers and others, and in 1929 Keynes described him as ‘an ardent and persistent advocate of the policy of appeasement’. Of course, Churchill staunchly (though not without wobbles) resisted the appeasement of Hitler. And his greatest achievement, as Roberts says, was to prevent his foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, from negotiating a settlement with Germany after the collapse of France, though this assessment hardly jibes with the account in Roberts’s biography of Halifax, The Holy Fox, where Churchill is likened to Mr Micawber and said to have been willing to accept ‘reasonable terms’.

In this new book, by contrast, there are many instances of special pleading on Churchill’s behalf. Roberts suggests that Churchill didn’t really mean his denunciations of Indians as ‘beastly people’ and a ‘foul race’, these apparently being expressions of his ‘provocative humour’. He exaggerates Churchill’s ‘lifelong philo-Semitism’ – after the Stern Gang assassinated his friend Lord Moyne, Churchill refused ever again to meet the Jewish leader Chaim Weizmann. While rightly arguing that Churchill was committed to the Empire and wanted Britain to be in Europe but not of it, Roberts attributes too much consistency to a statesman who, as Lord Beaverbrook said, had held every opinion on every subject. (The subliminal message, speculative at best, seems to be that Churchill would now be a Brexiteer.) Roberts also tries to kick Churchill’s famous ‘black dog’ – his depressions – into the dustbin of history. ‘It is unlikely’, he maintains, ‘that Churchill was a depressive at all.’ Yet Churchill himself referred to ‘those terrible and reasonless depressions wh[ich] frighten me sometimes’. His successes were all the more impressive for being achieved while the black dog prowled at his heels.

Still, Roberts celebrates those successes with infectious enthusiasm. He brilliantly conjures up one of the most fascinating characters of all time. He enriches the saga with wonderful examples of Churchill’s aristocratic eccentricity, glittering oratory and wit – no one in public life deployed jokes more promiscuously and effectively, as when he dubbed Attlee’s Britain ‘Queuetopia’. While not quite getting to grips with Churchill’s egotism and ruthlessness, Roberts salutes his transcendent qualities of courage, eloquence, energy, magnanimity, tenacity, audacity, humour and imagination. He also enters into Churchill’s conceit that he was a man of destiny – ‘over me beat the invisible wings’. Yet Roberts acknowledges that Churchill was, from his adventurous youth to his political apotheosis, incredibly lucky. Churchill himself would have agreed: he likened becoming prime minister to winning the Derby.

Some years ago I gave a talk about Churchill as an artist to an audience at the Royal Academy which included his daughter Mary, who had written a book on the subject. It was, I said, rather like a curate preaching in front of the pope, but I managed to avoid disaster by drawing copiously on Churchill’s own addresses to the Royal Academy. These have now been collected into an attractive volume by David Cannadine, whose introductory essay is characteristically elegant and erudite. As he shows, Churchill was a skilled amateur whose struggles at his easel banished gloom. His paintings resembled his speeches in being ‘bright, warm, vivid, highly-coloured and illuminated creations, full of arresting contrasts between the light and the dark’.

Churchill’s ‘daubs’ (his word) were largely influenced by Impressionism, though he once lovingly ran his fingers over the surface of old masters in the Louvre. He had little conception of modern art and invited Sir Alfred Munnings to join him in kicking Picasso’s arse. Yet he came to recognise that artistic freedom was vital to any society that valued liberty. This emerges strongly in the superb oration he delivered at the Royal Academy in April 1938. Without mentioning Hitler the chocolate box painter by name, he attacked him for incarcerating any artist who put too much green in the sky or too much blue in the trees. ‘Even more grievous penalties would be reserved for him,’ Churchill added mischievously, ‘if he should be suspected of preferring vermilion to madder brown.’

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

Give the gift that lasts all year with a subscription to Literary Review. Save up to 35% on the cover price when you visit us at https://literaryreview.co.uk/subscribe and enter the code 'XMAS24'