Piers Brendon

Demonstrate or Procreate

The Long ’68: Radical Protest and Its Enemies

By Richard Vinen

Allen Lane 446pp £20

To be young in 1968 was not very heaven but, as we oscillated between hope and dread, it was certainly an exciting time to be alive. In and around that year, a period that Richard Vinen calls ‘The Long ’68’, progress was palpable. Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society promised to realise Martin Luther King’s dream. Winds of change were blowing through colonised continents. Vatican II seemed to augur a modernised Roman Catholicism. British laws were reformed in matters such as abortion, homosexuality, censorship, divorce and equal pay for women. Counterculture flourished and, along with a whiff of cannabis, idealism was in the air. It was often naive. My own contribution was to produce and distribute, with friends, posters saying ‘Rhodesia: One Man One Vote’. It never occurred to us that they should have said ‘Zimbabwe: One Person One Vote’.

The decade reached its climax with les événements, the civil strife that engulfed France in May 1968. Protesting against American participation in the Vietnam War and the evils of capitalism generally, students marched, occupied their campuses and erected barricades, though these were more acts of performance art, says Vinen, than pieces of military engineering. Paris, the centre of the disturbances, saw its worst street violence since the Second World War. To everyone’s surprise, including that of trade union leaders, millions of workers backed the demonstrations, mounting a general strike that brought France to a virtual standstill. They wanted better pay and conditions but sometimes made no specific demands, suggesting that theirs was an assault on the entire social order. Anticipating another revolution, some Frenchmen didn’t bother to fill in their tax returns.

Student unrest erupted elsewhere in Western Europe and America, the focus of Vinen’s book, but it attracted little working-class support. As a result it was relatively mild and a mere blip on the political radar compared to China’s simultaneous Cultural Revolution, which, as far as the citizens of the democracies were concerned, was taking place in a faraway country of which they knew little. However, the Western uprisings, though all inimical to US militarism, differed in their emphases. American radicals campaigned against racism. In Germany students resisted anything that smacked of Nazism. Young British leftists espoused nuclear disarmament and opposed elitism, but generally eschewed extremism.

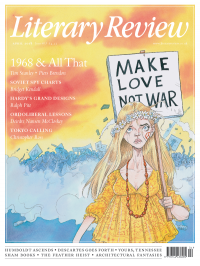

Admittedly, students and others attacked the American embassy in Grosvenor Square, but at a subsequent anti-war rally they linked arms with policemen and sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’. The home secretary, James Callaghan, mingled with demonstrators and laughed at Quintin Hogg’s request that a Guards regiment be held ready to quell them. The British anarchists known as the Angry Brigade killed no one, unlike the Baader-Meinhof Group in Germany and the Italian Red Brigades. The NUS leader, Jack Straw, who always had his eye on the main chance, danced with the Duchess of Kent. Flower children intoned ‘Make love, not war’ – and were reminded by the cartoonist Trog that Lloyd George had done both.

What united the rebels across borders was not a common ideology but a utopian afflatus. It was inspired by all sorts of factors: the reformism of the early 1960s, the writings of authors as various as Albert Camus, Frantz Fanon and C Wright Mills, the rhetoric of Martin Luther King, protest songs such as Joan Baez’s ‘We Shall Overcome’ and Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, even T-shirts featuring Che Guevara and Angela Davis. Spiro Agnew, later US vice president, went so far as to blame the advent of hippies, beatniks, flag-burners and their ilk on Dr Spock, who had liberalised babyhood. Equally extravagant were the ambitions of radicals themselves, which ranged from transforming society to levitating the Pentagon. One young Situationist attempted to undermine faith in consumer capitalism by dressing up as Santa Claus and handing out free gifts to surprised children from the shelves of Selfridges’ toy department.

All too soon, however, fear and loathing began to supersede heady optimism. In April 1968, King was assassinated, Enoch Powell made his ‘rivers of blood’ speech and London dockers marched in his support. De Gaulle led a right-wing backlash in France and at a huge Paris rally on 27 May there were shouts of ‘Cohn-Bendit to Dachau’. In June Robert Kennedy was shot. Two months later Russian tanks crushed the Prague Spring and Chicago mayor Richard Daley’s police rioted against demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention. When Senator Abraham Ribicoff denounced these ‘Gestapo tactics’, Daley was heard to respond, ‘Fuck you, Jew son of a bitch.’ In October street battles occurred in Londonderry. On 6 November, Richard Nixon was elected president of the United States.

Vinen says that his book is ‘an attempt to reconstruct the world’ in which such events took place. In this it fails. It does not conjure up the zeitgeist. It seldom captures the early exhilaration and later anguish that many of us experienced at the time, though Vinen does cite the US politician Daniel Moynihan’s remark that in 1968 the USA came close to a ‘nervous breakdown’. Vinen is austerely analytical rather than engagingly descriptive. He provides a bloodless dissection of causes and consequences rather than a vivid evocation of the human drama. With subheaded sections in each chapter, moreover, his work has the air of lecture room and textbook.

On the other hand, Vinen probably understands the long ’68 better than other historians, and better too than the participants themselves, who recall it now with fading memories, and even at the time frequently hadn’t a clue what was happening, relying for information on their new transistor radios. His knowledge, presented in good workmanlike prose with proper references, is encyclopaedic. He has a fund of telling anecdotes, often wittily recounted: for example, he notes that in April 1968 ‘the FBI took time out from spying on anti-Vietnam War demonstrations to report that women had broken rules at the University of New Orleans by wearing slacks’. Above all, Vinen skilfully teases out the nuances, anatomises the complexities and elucidates the paradoxes of the period.

For instance, de Gaulle dismissed the protests as chie-en-lit, yet he had much in common with the gauchistes responsible for them: disdain for the consumer society, hostility to America and opposition to the Vietnam War. Much the same could be said of Powell, and even LBJ shared the students’ concerns about poverty and race discrimination. Communist parties and trade union bosses, the natural allies of the demonstrators, disliked the spontaneous effervescence, which they could not control. Although much was made of generational conflict, parents and children were often in accord, while professors and students did not find it too hard to agree on reforming syllabuses and teaching. In the changing climate of opinion, gays became more militant, but so too did bigots. The unreconstructed construction workers wearing hard hats who attacked a rally in New York against the shooting of Kent State University students displayed placards saying ‘Don’t worry – they don’t draft faggots.’

The slogan ‘Sisterhood is Powerful’ was coined in 1968 and many women did feel empowered by the experience of protesting. Women’s Lib gathered strength. In France feminists mocked traditional, restrictive morality, calling it ‘tante Yvonne’. In America the Weathermen changed their name to the Weather Underground. Yet women were marginalised by the protests, shouted down, told to make the tea. The Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael famously quipped that the position of women in the revolution should be ‘prone’. ‘Rape your alma mater’ urged a Paris graffito and the Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver apparently believed that ‘rape was an insurrectionary act’. The pop scene was dominated by male chauvinists such as Mick Jagger, who wanted to have women under his thumb, and John Lennon, who pronounced that ‘Women should be obscene and not heard.’ When Margaret Thatcher visited Lanchester Polytechnic in 1971 as secretary of state for education, students shouted, ‘Fascist pig; get her knickers off.’

What was the legacy of 1968? It prompted a conservative reaction, with electoral victories for Nixon, de Gaulle and Heath. Trade unions and their members gained in the short term but the ultimate beneficiaries were Thatcher and Reagan – he regarded the Berkeley manifestations as a symptom of national malaise and condemned the promiscuity of men who ‘dress like Tarzan, walk like Jane and smell like Cheetah’. Many of the young agitators joined the political mainstream or became pillars of the acquisitive society. In 2008 Cohn-Bendit, by now an MEP, declared, ‘1968 is finished’. Yet, along with helping to force America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, the ’68ers permanently changed attitudes towards race and civil rights. They embodied a progressive spirit that, as Vinen suggests at the end of his able, intricate study, survives even in the era of Brexit and Trump.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In fact, anyone handwringing about the current state of children's fiction can look at over 20 years' worth of my children's book round-ups for @Lit_Review, all FREE to view, where you will find many gems

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Philip Womack

literaryreview.co.uk

Juggling balls, dead birds, lottery tickets, hypochondriac journalists. All the makings of an excellent collection. Loved Camille Bordas’s One Sun Only in the latest @Lit_Review

Natalie Perman - Normal People

Natalie Perman: Normal People - One Sun Only by Camille Bordas

literaryreview.co.uk

Despite adopting a pseudonym, George Sand lived much of her life in public view.

Lucasta Miller asks whether Sand’s fame has obscured her work.

Lucasta Miller - Life, Work & Adoration

Lucasta Miller: Life, Work & Adoration - Becoming George: The Invention of George Sand by Fiona Sampson

literaryreview.co.uk