David Gelber

Down with the Crown?

Abolish the Monarchy: Why We Should and How We Will

By Graham Smith

Torva 264pp £16.99

Is the Metropolitan Police a republican fifth column? Since it hauled the author of this book off to the cells hours before Charles III’s coronation, in full sight of the world’s media, the campaign group he heads, Republic, has almost doubled its membership. When the police clapped him in handcuffs, Graham Smith was preparing to perform that most fearful of treasons: shuffle around Trafalgar Square waving a placard bearing the words ‘Not my king’. Smith’s sixteen hours in police custody has generated more publicity for his organisation than the eighteen years he’s toiled away campaigning to replace the monarch with an elected head of state.

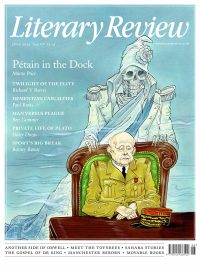

Abolish the Monarchy was written before Smith’s rendezvous with the law. Although he is committed enough to the republican cause to lay down his freedom for it, there is something not altogether serious about the book he has produced. The dust jacket, with its silhouette of St Edward’s Crown upturned, gives it the appearance of a lost Sex Pistols album. The royal purple endpapers raise the thought that his publisher is having a laugh at his expense.

But the unseriousness goes beyond superficialities. Smith believes that monarchy’s failings are so self-evident that it is unnecessary to treat it seriously as a system of government. One could be forgiven, after reading this book, for thinking that no greater intellects than Alan Titchmarsh and Stephen Fry have turned their minds to the subject. There is no reference to Thomas Hobbes or Edmund Burke, let alone other, less famous, theorists of monarchy. There is no engagement with the writings of the German historian Ernst Kantorowicz, who exposed the sophistication of monarchical conceptions of the state. To this day, many of these ideas underlie the operations of the British monarchy – too often called ‘constitutional’, notwithstanding the absence of anything resembling a constitution.

More surprising still, given that he leads a group called Republic, Smith appears to have little familiarity with the 2,500-year-old tradition of republican thought. Where are Plato, Machiavelli and Rousseau? Where are the Levellers, the Radical Whigs and the Founding Fathers? Thomas Paine does get a mention, though one is left with the suspicion that Smith’s acquaintance with him comes via The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations rather than Rights of Man, since he is invoked merely to make the point that the appearance of something being correct doesn’t make it so.

To give Smith the benefit of the doubt, it could be argued that the general public, at which this book is aimed, would quickly lose interest in a work clotted with centuries-old theories. Yet in their absence there is a void. The reader is left with no sense of the principles that would underpin the republic Smith desires. Questions about the source of its legitimacy and the contract between citizen and state go unaddressed, as does the big one: why is a republic more conducive to human wellbeing than a monarchy? Monarchists, with a deep well of historical precedent and the benefit of the status quo to draw from, have answers to these questions. Republicans must too.

Britain, of course, is not bereft of experience when it comes to abolishing monarchy. The historical examples, however, are more of a hindrance to republicans than a help. Smith, understandably, stays silent on the cases of the Commonwealth and the Protectorate, involving as they did regicide, military dictatorship and ultimately the kind of dynasticism that republicanism is meant to impede. Indeed, perhaps to burst any preconception that he is a Cromwellian killjoy, Smith spends the first few pages chronicling a tour of Buckingham Palace he took with his nephews. As a history enthusiast, he says, he wishes it were possible to take in the palace in all its splendour, not just the few rooms the monarch has condescended to leave unlocked. It’s a disarming opening, for sure, but – on the principle that you should always lead with your strongest suit – also an odd one, for, as Smith himself eventually says, questions of tourism are irrelevant to constitutional arrangements.

Unwilling to make the case for republicanism on its own merits, Smith builds his argument on the apparent shortcomings of monarchy itself. Both in principle and in practice, he states repeatedly, monarchy contravenes the ‘values’ of the British people: it is undemocratic, expensive and impractical; it enthrones privilege, nepotism and inequality. He offers up a familiar list of royal peccadilloes – King Charles’s petulance, Prince Andrew’s promiscuity, Prince William’s indolence – and slays sacred cows along the way: Queen Elizabeth II was a tax evader; her mother was a racist; their Tudor and Stuart precursors were slave traders.

Although he is in favour of an elected head of state, Smith doesn’t spare politicians. The operations of government under the monarchy are supposedly no less offensive to public morals than the transgressions of individual kings and queens. Monarchy, he states, has enabled executive overreach, allowing prime ministers to exercise without restraint powers, such as waging war, granting honours and calling elections, traditionally vested in the crown. One of the stronger passages examines the prorogation affair of 2019 and the paralysis that overcame the queen as she struggled to reconcile her role of constitutional backstop with the expectation that the monarch do nothing to impede an elected government. Smith diagnoses this extraordinary episode, which culminated in the Supreme Court resorting to a legal fiction to annul Boris Johnson’s six-week suspension of Parliament, as a failure of monarchy. A more precise reading would be that it exposed the phantasmal quality of the so-called British constitution. A president put in a similar position to the queen, without constitutional protocols to follow, would have encountered the same troubles.

The obvious problem with the moralistic approach is that any society, let alone one of sixty-five million people, will harbour a vast diversity of values, as is borne out by recent polls of public attitudes to the monarchy itself. Perhaps unwittingly, Smith concedes as much. He says that the attitudes of the royal family to race are contrary to the nation’s sense of fairness and equity. At the same time, however, he refers to the outpouring of public support for the courtier Lady Susan Hussey when she was accused of racism.

Rather than take a values-neutral approach to issues beyond the narrow question of how the head of state should be chosen, Smith makes republicanism a vessel for his own values, which he dresses up as those of the British people. We should abolish monarchy, he says, because it stands for prejudice, elitism, favouritism and the like, values which are anathema to the British people. Yet all these things, he also acknowledges, are alive and at large in society. On the question of government power, Smith likewise assumes that the existence of a strong executive is at odds with British values. The events of 2019 suggest that there is little accord among the public on this matter either.

Which takes us to the ‘how we will’ part of abolishing the monarchy. It will be achieved, says Smith, by forcing the public to come to its senses about the chasm between its own values and those of the crown, perhaps by giving everyone a copy of this book. Eventually, the government will be unable to ignore public clamour for a referendum on the monarchy’s continuation. Then, the crown will simply be voted out of existence. Smith is hazy on the itinerary, but that doesn’t stop him looking forward to a time when the ‘champions of our most cherished shared values’ appear in place of the king on stamps, and the likes of Carol Ann Duffy are put to work writing a republican constitution. If you were hoping that the fall of the Windsors would at least mean no more tampon metaphors, think again.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

The son of a notorious con man, John le Carré turned deception into an art form. Does his archive unmask the author or merely prove how well he learned to disappear?

John Phipps explores.

John Phipps - Approach & Seduction

John Phipps: Approach & Seduction - John le Carré: Tradecraft; Tradecraft: Writers on John le Carré by Federico Varese (ed)

literaryreview.co.uk

Few writers have been so eagerly mythologised as Katherine Mansfield. The short, brilliant life, the doomed love affairs, the sickly genius have together blurred the woman behind the work.

Sophie Oliver looks to Mansfield's stories for answers.

Sophie Oliver - Restless Soul

Sophie Oliver: Restless Soul - Katherine Mansfield: A Hidden Life by Gerri Kimber

literaryreview.co.uk

Literary Review is seeking an editorial intern.