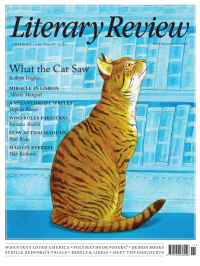

Kathryn Hughes

Hooked on a Feline

Jeoffry: The Poet’s Cat

By Oliver Soden

The History Press 185pp £16.99

Lost Cat

By Mary Gaitskill

Daunt Books 89pp £8.99

Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life

By John Gray

Allen Lane 128pp £20

One day in 1757 the poet Christopher Smart went out to St James’s Park, started praying loudly and couldn’t stop. He was hauled off to St Luke’s Asylum, where a cascade of ecstatic verse proceeded to pour from him, in which he identified his cat companion, Jeoffry, as ‘the servant of the Living God’. According to Smart’s delighted itemising, Jeoffry served the Almighty by catching rats, keeping his front paws pernickety clean and observing the watches of the night. He was a peaceable soul too, kissing neighbouring cats ‘in kindness’ and letting a mouse escape one time in seven. But perhaps Jeoffry’s greatest accomplishment was his ability to ‘spraggle upon waggle’. Both spraggling and waggling, Smart’s magnificat suggests, are deeply pleasing to the Lord.

Although Jeoffry has become famous through Smart’s much-anthologised poem ‘My Cat Jeoffry’, he has left no other pawprint on the historical record. We don’t know how Smart found him, or how he found Smart. Nor is it certain what became of him after the poet was released in 1763 and restarted his life as a denizen of Grub Street, a huge comedown for a one-time fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge. It is this gap that Oliver Soden proceeds to plug in his delightful ‘biography’ of Jeoffry. Soden decides that Jeoffry is rust-coloured. He starts him off in a Covent Garden brothel, where he spends his kitten days chasing used condoms across the floor, avoiding piss pots and wondering at the meaty smells emanating from the bed under which he crouches while his mistress, Nancy Burroughs, doggedly transacts her business. This setting gives Soden the perfect chance to provide colour to the black-and-white world of William Hogarth’s prints, a riotous jumble of muck and mayhem, law and disorder, moral and amoral decline. He even rifles through Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies for 1761 to give Nancy a back story: she is ‘very ugly; chiefly a dealer with old fellows’ who specialises in the birch.

Soden also takes care to incorporate every well-known real-life cat story from the 18th century, even when it means going on narrative walkabout. So we are told about Horace Walpole’s tabby Selima, who in 1747 topples into a goldfish bowl and drowns, only to be resurrected by Thomas Gray in ‘Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat’. We also zoom over to Dr Johnson’s house to see the Great Lexicographer assuring his sleek darkling Hodge that he is ‘a very fine cat indeed’.

The literary allusions don’t stop there. Indeed, the whole of Soden’s book is a determined homage to Flush, an imaginary biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel that Virginia Woolf concocted in 1933 out of his fleeting appearances in the poet’s letters. Just like Woolf, Soden uses his animal protagonist to reimagine the world from eighteen inches above the ground. In a particularly fine evocation of a cat’s-eye view, Soden has Jeoffry distinguish Smart’s asylum visitors from each other by the shape of their lower legs: he is able to tell apart the bulging calves and hobbled feet of Dr Johnson and the more springy limbs of Charles Burney. When David Garrick arrives, Jeoffry recognises him from the way the actor’s theatrical vibrato moves the air in the little cell. It is, after all, what whiskers are for.

‘My Cat Jeoffry’, which is a fragment of a much longer poetic sequence called Jubilate Agno, lay unregarded for nearly two centuries until it was published in The Criterion under the editorship of T S Eliot in 1938. A similarly winding path has been taken by Mary Gaitskill’s extended essay Lost Cat, which has had, if not exactly nine lives, then quite a few already. Published first in 2009 in Granta, it then appeared as the lead piece in a collection of the American novelist’s nonfiction in 2017. Now here it is again, this time travelling quite alone, which, of course, is exactly how every self-respecting cat prefers it.

Lost Cat deals with what seems like Gaitskill’s excessive reaction to losing Gattino, a little one-eyed cat whom she has rescued from Italy and brought back to her New England farmhouse at great trouble and expense. One night Gattino stalks off into the bone-freezing landscape, leaving Gaitskill reduced to increasingly demented behaviour – the sort of thing that, two centuries earlier, would have had her admitted to the asylum. She leaves trails of urine-soaked cat litter over the pristine snow in the hope that Gattino might pick up the scent and scuttle back home. She consults expensive psychics who tell her both that the little cat died peacefully and that he passed away in agony. With every knock and rustle of the rural night she thinks she hears him calling.

This is not just some crazy-cat-lady story. In disconsolate prose, an absolute counterpoint to Smart’s Jubilate Agno, Gaitskill teases out why she has become undone by the loss of her cat. It could be her failure to absorb the death of her father several years earlier – to deal with the loss of a man who sounds distinctly tricky. Or perhaps it is to do with the more recent struggles she has faced in fostering two children, Caesar and Natalia, from the inner city. Initially they seem to flourish under the novelty of Gaitskill’s interest, enjoying a generous supply of tutors, riding lessons and trips to summer camp. But then they pull away, as if wanting to punish her for her foolish fondness, just as Gattino seems equally indifferent to the superhuman efforts she has made on his behalf.

That, though, is the way of cats according to the philosopher John Gray, who references both Jeoffry and Gattino in his magnificent Feline Philosophy. Cats, argues Gray, are not burdened by self-consciousness, which leaves them free to be magnificently themselves. They live in a world of materiality – of cushions, mice, hunger and heated blankets – and adjust themselves accordingly. If something doesn’t suit them, they move on and find something better. They are not being unkind and they have no sense of wanting to punish an owner who has failed to come up with the goods. But they follow the beat of their own conatus, a term Spinoza used to suggest a kind of inner drive to live the life that suits you best, even if that means bringing up fur balls on the carpet at four o’clock in the morning.

It is this absolute sense of entitlement that explains why the cat has historically been the object of choice whenever civilisation went looking for something handy onto which to project its discontents. Every time a carnival crowd dressed up a cat as the pope before torching it, or drunken ’prentice lads rampaged through the town strangling strays, or a housemaid kicked the resident mouse-catcher when her mistress wasn’t looking, they were expressing profound envy of a creature that refused to feel bad about itself. Cats are so enraging in the wrong hands, suggests Gray, because, unlike dogs, they never descend to our level.

If only, Gray concludes, we could all try to be a bit more catlike we would be so much happier. Or at least less unhappy. This doesn’t mean, mercifully, that we should try licking our own bottoms (tricky, anyway, for the over-forties unless you’re very good at yoga). It does mean realising, though, that it is better to be indifferent to others than to feel you have to love them. ‘Few ideals’, suggests Gray, sounding like a particularly grumpy tortoiseshell who has been kept waiting for his Felix, ‘have been more harmful than that of universal love.’

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Though Jean-Michel Basquiat was a sensation in his lifetime, it was thirty years after his death that one of his pieces fetched a record price of $110.5 million.

Stephen Smith explores the artist's starry afterlife.

Stephen Smith - Paint Fast, Die Young

Stephen Smith: Paint Fast, Die Young - Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon by Doug Woodham

literaryreview.co.uk

15th-century news transmission was a slow business, reliant on horses and ships. As the centuries passed, though, mass newspapers and faster transport sped things up.

John Adamson examines how this evolution changed Europe.

John Adamson - Hold the Front Page

John Adamson: Hold the Front Page - The Great Exchange: Making the News in Early Modern Europe by Joad Raymond Wren

literaryreview.co.uk

"Every page of "Killing the Dead" bursts with fresh insights and deliciously gory details. And, like all the best vampires, it’ll come back to haunt you long after you think you’re done."

✍️My review of John Blair's new book for @Lit_Review

Alexander Lee - Dead Men Walking

Alexander Lee: Dead Men Walking - Killing the Dead: Vampire Epidemics from Mesopotamia to the New World by John Blair

literaryreview.co.uk