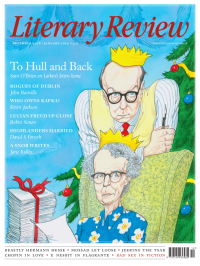

Sean O'Brien

How Exciting about the Lavatory!

Philip Larkin: Letters Home 1936–1977

By James Booth

Faber & Faber 612pp £40

Writing to Monica Jones in 1954, Philip Larkin describes his mother, Eva: she is ‘nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self-pitying. It’s no use telling her to alter: you might as well ask a sieve to hold water.’ Larkin might be sketching a grim self-portrait on a gloomy Sunday afternoon for want of a poem to write. ‘On the other hand, she’s kind, unselfish, loving,’ he continues, before concluding, not quite coherently, ‘Am I, ultimately, on her side? God knows! In my heart of hearts I’m on no one’s side but my own.’

It takes a degree of resolution to set about reading a book of nearly seven hundred pages consisting largely of letters to an increasingly sad and isolated old lady. What Larkin may have claimed not to do for love he certainly did for duty, once a week and sometimes twice. In 1972 he wrote to her 277 times. His letters home number about four thousand in total, as do Eva’s replies. It’s often absorbing stuff, though increasingly grim. James Booth, a recent biographer of Larkin, has made a substantial, thoroughly annotated selection from this vast correspondence, adding to the two previous volumes of Larkin’s letters (both edited by Anthony Thwaite), Selected Letters of Philip Larkin 1940–85 and Letters to Monica. The poems, in fact, are dwarfed by the letters. One is tempted to say, thank God Larkin had his diaries burned, but only for a moment.

The earliest letters are sometimes very funny, as Larkin tries on attitudes. At Oxford he claims to be lumbered with ancient and/or mentally defective tutors; his work appears in magazines but is no good; he is upbraided when he reads for pleasure. He tailors his tone to the recipient: bluff and undeluded for Sydney Larkin (‘Pop’), safely and tenderly domestic for Eva (‘Mop’) and affectionately satirical for his older sister, Kitty. He includes some moody Oxford scenery: ‘the playing fields wait for the games of this afternoon; through the unecstatic street the gowned bicycles are whirling.’ This is pretty sophisticated for an eighteen-year-old – partly a parody of the promised bicycle races in Auden’s ‘Spain’, partly the kind of ‘real’ thing that finds its way into Larkin’s poetry and fiction. His description of trying to access a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover at the Bodleian is a small-scale classic that would slot perfectly into Lucky Jim. You enjoy the voice without ever quite believing what Larkin says, but ‘what he says’, the making over of the humdrum world of college and digs into curmudgeonly comedy, is what matters. This spirit of negation persists into his maturity, but it hardens from playfulness into habit.

In 1940 he writes to Kitty, ‘I was made for peace’, in a passage that seems to foreshadow the ‘secret, bestial peace’ of the firelit Dutch drinkers in the wonderful sonnet ‘The Card-Players’, written thirty years later. When it comes to the war, Larkin does his share of fire-watching. He hitchhikes anxiously back to his home town of Coventry (his father was city treasurer) after it is terribly bombed. The war was omnipresent, so perhaps there was no need to write about it all the time; or you might think that Larkin’s reticence is perhaps not unrelated to Sydney’s extremely right-wing convictions. Pop had a mechanical statue of Hitler on the mantelpiece (Booth, rather missing the point, comments in his biography that it was only a small one). Writing to his mother in 1974, Larkin explains that he has been busy discussing arrangements for a visit to Hull University by the German ambassador: ‘Daddy would feel happier about it than I do! Still, they all speak very good English, so I suppose it will be all right. I asked the Professor of German if I should put our copy of the Ist ed. of Mein Kampf on exhibition, but he said he thought not!’ This is skilfully made to measure for both its recipient and a more knowing posterity, complete with the Alan Bennett-like non-sequitur about the visitors’ fluent English. Larkin walks on the edge of a minefield, testing an anxiety rather than drawing a conclusion. He investigated his father’s papers and was relieved to find no evidence connecting him to pro-Fascist outfits such as The Link.

Declared unfit for military service because of poor eyesight and armed with the first-class degree he claimed not to have expected (‘I have moments of panic when I think I shall be “thirded”’), Larkin starts work in the library at Wellington in Shropshire, slowly taking over from his elderly predecessor as he sets about studying his profession and putting its principles into effect. For want of society he writes vividly detailed and amusing letters taking in the view from the issue desk. He improves the stock, encourages library users to explore further than ‘two westerns for grandad and a lover for my mother’ and hears ‘third hand’ the accusation that he has been ‘filling the Library with filthy books’. He grows accustomed to handling committees. Meanwhile, his friend Bruce Montgomery makes waves with his detective stories, and Larkin complains that if his evenings were free he would write more, which is all he really cares about. Up to a point this is true, but Larkin was his father’s son in bringing a professional commitment to his administrative role. Given his decreasing poetic productivity in later years and the fact that he’d given up writing novels, free time might have been a dangerous burden when youthful indulgence turned into the glum habits of middle age: ‘I work all day, and get half-drunk at night’, as his last major poem, ‘Aubade’ (1977), puts it. The ‘toad work’ clearly assisted the poet ‘down Cemetery Road’. When he began taking courses in librarianship he commented to his parents, ‘I feel I am setting off down a long dark road lined with broken rocks and ending in perpetual night.’ The perpetual night, as it turned out, was spent in Hull.

Booth points out that Larkin is ‘notably reticent’ about Ruth Bowman, whom he met at the library when she was a schoolgirl of sixteen. It was an increasingly agonised relationship, taking in two proposals and their swift withdrawal. Unsurprisingly, given that his mother was usually the recipient of his letters, we learn little here of his feelings about any of the other women with whom he was involved: Monica, Patsy Strang, Maeve Brennan and Betty Mackereth, though the last two figure as colleagues and friends.

Perhaps we shouldn’t underestimate Eva Larkin. Very late in life she was rereading Sons and Lovers and enjoying The Trumpet-Major, though following Sydney’s death in 1948 she was increasingly afflicted by anxiety and indecision. She feared thunderstorms, and when invited to watch a neighbour’s television she became alarmed by the weather forecast. Thoughts of moving house or acquiring a live-in companion occupied her minutely. Loneliness was a grim affliction, though her daughter lived nearby and Larkin visited with what seems heroic frequency until her death in 1977 at the age of ninety-one, when dementia had overtaken her.

By the 1960s, Larkin was often scraping the barrel for anything to say. Constants are the price and (usually poor) quality of food, suit material at so much a yard, buying socks and so on. He might be one of Muriel Spark’s bachelors, with their refrain: ‘Your hand’s never out of your pocket.’ There are moments of relief: ‘How exciting about the lavatory!’ Larkin’s affection is steadfast, though in later years he apologises for losing his temper while visiting.

Readers may suspect that it was not only Eva who suffered from depression. Professional responsibilities, especially overseeing the building of the new library at Hull University and its later extension, combined with steadily increasing literary fame seem almost to have suffocated Larkin. His disappointment is pre-emptive. He often displays a sour, impertinent contempt: for people shopping in Hull marketplace, for striking railwaymen (‘idle swine’), for the Irish and for immigrants whose ‘germs’ he might catch in London. In this vein he sounds as provincial as he thinks nearly everyone else is. His comments on other writers are horribly funny in their unfairness, though. Alan Bennett is ‘a so-called comedian’. As for Ted Hughes, ‘he is as famous as I am, only younger: a great thug of a man, never does any work. I rather envy him.’ After meeting Geoffrey Hill, Larkin states, ‘He struck me as rather a dismal Jimmy.’ And here and there, among the letters to the Coal Board about Eva’s defective heating, and the dreaded meetings of the library committee, and the downstairs neighbours playing their accursed horns, we glimpse the emergence of the poems. Eva liked and admired them, and was in this respect rightly proud of her son, who, in turn, seems to have done his best for her.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

The son of a notorious con man, John le Carré turned deception into an art form. Does his archive unmask the author or merely prove how well he learned to disappear?

John Phipps explores.

John Phipps - Approach & Seduction

John Phipps: Approach & Seduction - John le Carré: Tradecraft; Tradecraft: Writers on John le Carré by Federico Varese (ed)

literaryreview.co.uk

Few writers have been so eagerly mythologised as Katherine Mansfield. The short, brilliant life, the doomed love affairs, the sickly genius have together blurred the woman behind the work.

Sophie Oliver looks to Mansfield's stories for answers.

Sophie Oliver - Restless Soul

Sophie Oliver: Restless Soul - Katherine Mansfield: A Hidden Life by Gerri Kimber

literaryreview.co.uk

Literary Review is seeking an editorial intern.