Matthew Parris

How Very Interesting

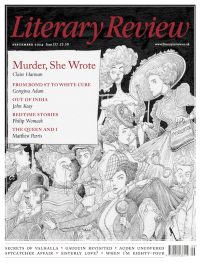

A Voyage Around the Queen

By Craig Brown

Fourth Estate 672pp £25

In June 2001, I was at a reception for the president of South Africa at Windsor Castle, deep in conversation with that county’s minister of tourism and irritated that someone was insistently tapping me on the shoulder. Turning around, I realised it was a courtier. Behind him stood Queen Elizabeth II, talking to somebody else. I had not realised that this is how monarchs must socialise: ploughing steadily through the throng with a flunkey just ahead, readying each new guest for a short encounter, for which the royal person has been briefed beforehand. So she knew I wrote about politics.

‘I do feel sorry for Mr Hague,’ she said (William had just announced his resignation as Tory leader). ‘It must be dreadful to forsake the great ambition of your life when still so young.’ ‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘but perhaps it was his youth that was the problem.’ Short pause. ‘How very interesting.’ Then she moved on.

Craig Brown devotes a whole short section of A Voyage Around the Queen to the late Queen Elizabeth’s stock-in-trade ‘How very interesting’, along with its variations, ‘How interesting’ and ‘How very, very interesting’, and the brisk dispatch with which she would terminate conversations before they did get interesting. Seated in the parlour at Buckingham Palace, she would actually ring a bell to prompt the ushering out of a guest.

This, and a million other snippets of information, I learn from Brown’s monumental gathering in of virtually everything we can know about the queen’s life, from birth to death. Indeed, he points out that most of us know more about her life than we do about our own parents’ – let alone grandparents’ – lives.

A Voyage Around the Queen is a massive magpie’s nest of sticks and leaves and ribbons and tinfoil and tinsel and brightly coloured shreds of paper, many of them utterly trivial, individually inconsequential, a few of them profoundly telling, some old, some new, some obvious, some shocking, but in sum adding up to much more than a mere pile. This is a book about ourselves as a nation, reflected and refracted through our own relationships with one person, or our ideas of that person.

It’s no accident that Brown gives sustained attention to people’s dreams about the queen, for his subject is in itself a kind of dream, a national dream. The one thing I always hoped I might get a chance to ask her was whether she’d ever woken in the small hours and considered that, at that very moment, hundreds of people were dreaming about her.

Brown’s method is worth describing because it amounts almost to a new kind of history. There’s little or no primary research here and only a handful of stories that you or I could not in principle have tracked down in old newspaper cuttings or in other books, recordings and accounts already in the public domain. He has instead engaged in a truly massive project of gathering. His materials are newspaper reports, accounts written by intimates, gossip columns, anecdotes by those who met her, details of the personalities of her corgis and her relationship with dogs and horses, reflections on her in other people’s published diaries, documentaries, TV programmes. It amounts to a thousand glimpses through the eyes of others, some friendly, some fawning, some hostile, some coldly distanced.

At first it’s just a heap, but almost imperceptibly as the details mount up – a snippet from the Daily Express, an interview with a lookalike in the Daily Mail, worries about whether she will mind being driven in a car owned by a divorced man, the bourgeois decor of the royal yacht, a housewife’s spring-cleaning of an entire house in preparation for her visit to a single room, a nutter’s successful bid to break into her bedroom, the things people in crowds call out as she passes, the row with Tony Benn when he tried to remove her head from our postage stamps, a (priceless) genealogy of her corgis, the way her accent changed, grumpy entries in Chips Channon’s diaries – a picture begins to take shape, in the end powerfully. It’s a picture of ourselves.

Brown has perhaps only one serious thesis, stated at the outset. Almost everyone, he says, goes slightly bonkers in her presence. We gabble, we dry up, we lose our thread, we gawp, we stammer – and we talk about ourselves. She just listens. ‘How very interesting.’ Brown wonders whether it ever crossed her mind ‘that most of her subjects were deranged’. Perhaps nobody in Britain would be more successfully replaceable by AI, but Brown would reply that AI is, in the end, nothing but things we already know or feel, repackaged and presented back to us – and so was she. Was she just a screen on which we saw ourselves and our country, or was there an actual person in there?

There was one (and only one) occasion, described here by Marion Crawford, who wrote a memoir of her time as a royal governess, when the machine went berserk. ‘Lilibet’, aged seven, was being taught French by a stern, joyless and grammar-fixated ‘Mademoiselle’:

One day curious sounds emerged from the schoolroom. I went in to see what had happened. I found poor Mademoiselle shattered, and transfixed with horror. Lilibet, rebelling all of a sudden, and goaded by boredom to violent measures, had picked up the big ornamental silver inkpot and placed it without any warning upside down on her head. She sat there, with ink trickling down her face and slowly dyeing her golden curls blue. I never really got to the bottom of what had happened.

So out of kilter is this report with the angelic picture of the little princess that Crawford’s memoir assiduously painted that Brown is fairly sure the story is true. Was this perhaps the last audible cry for help ever uttered by the real human trapped within the royal machine?

Horseracing, he observes, was the one unplannable event in a life in which every waking moment was planned and fixed. Might this, he asks, be why the only two occasions in Elizabeth’s adult life on which she was spotted running – in 1954 and 1991– were at the races, when she had a winner?

On 4 June 2022, her horse, Steal A March, was running at Worcester, and the Queen was watching the race on her television at Windsor Castle. ‘She began to cheer it on so loudly that the security men rushed in, thinking something terrible was happening,’ recalled the horse’s trainer, Nicky Henderson. It was her Platinum Jubilee weekend; by then, she was 96 years old.

Is Brown a royalist or a republican? I don’t think he knows, and (extraordinarily) I can recommend A Voyage Around the Queen – wonderfully readable – to both lovers and haters of monarchy. He is by turns affectionate and scornful, but always absorbed. Although the satirist in him keeps breaking through, I cannot see Craig knitting at the tumbrils. He’s unsure, I think, what to make of his own fascination with his subject.

History’s a funny thing. The record, however faithful, often reads lifelessly, sails flapping idle when no longer filled with the wind of the times. You can write the facts but it’s hard to write the wind. Brown’s historiographical method – superficially trivialising – makes that wind blow. Stuffed with trash, this is a deeply serious book.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Alfred, Lord Tennyson is practically a byword for old-fashioned Victorian grandeur, rarely pictured without a cravat and a serious beard.

Seamus Perry tries to picture him as a younger man.

Seamus Perry - Before the Beard

Seamus Perry: Before the Beard - The Boundless Deep: Young Tennyson, Science, and the Crisis of Belief by Richard Holmes

literaryreview.co.uk

Novelist Muriel Spark had a tongue that could produce both sugar and poison. It’s no surprise, then, that her letters make for a brilliant read.

@claire_harman considers some of the most entertaining.

Claire Harman - Fighting Words

Claire Harman: Fighting Words - The Letters of Muriel Spark, Volume 1: 1944-1963 by Dan Gunn

literaryreview.co.uk

Of all the articles I’ve published in recent years, this is *by far* my favourite.

✍️ On childhood, memory, and the sea - for @Lit_Review :

https://literaryreview.co.uk/flotsam-and-jetsam