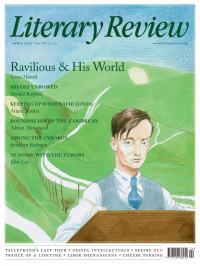

Tanya Harrod

Outbreak of Talent

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship

By Andy Friend

Thames & Hudson 336pp £24.95

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship, with a thoughtful introduction by Alan Powers, accompanies an exhibition of the same name at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne (27 May–17 September 2017), marking the 75th anniversary of Eric Ravilious’s death. Ravilious has been the subject of major exhibitions and monographs and it might seem that there is little more to say about this beguiling figure. But Andy Friend attempts something difficult and useful – a multiple biography of the network of artists in Ravilious’s circle, mostly his fellow students at the Royal College of Art, who came to maturity in the interwar years.

Some of the key figures in Ravilious & Co were indebted to the artist Paul Nash, who in turn had been recruited by the RCA’s inspired principal William Rothenstein. Nash spent some thirty days teaching in the School of Design in late 1924 and 1925. By April 1925 he was happy to resign from what he called his ‘usher’s job’ and get on with painting. But ten years later, in Oliver Simon’s magazine Signature, he recalled that his time there coincided with a rare ‘outbreak of talent’, a generation that included Ravilious, Edward Bawden and Enid Marx. Later, Nash generously found work for and promoted his most gifted students – Ravilious and Marx, Douglas Percy Bliss and Barnett Freedman. Bawden brilliantly made his own way from the start, getting graphic design commissions as soon as he left the RCA.

That Nash found so many gifted individuals in a department of design rather than one of fine art underlines the fact that the full story of interwar modernism in England cannot be written without equal reference to design, craft and fine art. Bawden, self-consciously, felt that the Design School at the RCA was the ‘habitat of the lowest of the low’. But it emerged as an important site of graphic innovation, unconcerned with what Bliss dismissed as the ‘representation of the naked human body’ that went on in the ‘over-heated and under-ventilated rooms’ of the Painting School. Significantly Bliss, Freedman and Marx, who came out of the Painting School, all turned to illustration and graphic design. Marx had in fact failed her painting diploma because of her abstract tendencies. But Nash recognised her unusual gift for pattern making, introducing her to the Curwen Press and praising her in his 1926 article ‘Modern English Textiles’, along with the great woodblock textile artists Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher, to whom Marx was apprenticed. He gave her, Ravilious and Bawden further publicity by including them in ‘Room and Book’, his utterly original 1932 show at the Zwemmer Gallery, which set out to demonstrate how a modern movement house might be furnished.

Between the wars, progressive British art encompassed wood-engraving and the craft of handblock-printed textiles. These were genres that required precision and resolution, comparable in some ways to direct carving in wood or stone. Indeed, in 1932 the Zwemmer Gallery chose to show a Henry Moore sculpture against the backdrop of a handblock-printed textile by Marx. A determination to work directly also characterised Ravilious’s watercolours, painted with a dry brush and a drastic simplification of the subject matter, as much design logic as fine art. Other unexpected art forms enriched British modernism in those years, including pottery (not discussed by Friend) and puppets. Ravilious’s lover Helen Binyon performed her ‘Jiminy Puppets’ to music specially composed by Benjamin Britten and Lennox Berkeley, offering a Gesamtkunstwerk in miniature.

Although Ravilious is necessarily the book’s charismatic focus, Friend skilfully keeps track of many lives. Art school scholarships gave rise to a diverse social milieu – something that may not be the case today. Ravilious’s youth was haunted by his feckless father’s money worries and bankruptcy, Freedman’s disadvantaged East End childhood had been dogged by illness and Percy Horton, later a fine teacher and involved with the Artists International Association, had experienced a brutal period in prison during the First World War as a conscientious objector. The women in the story came from more privileged backgrounds – Binyon was presented at court, Tirzah Garwood, a colonel’s daughter, had to fight to be allowed to marry Ravilious, Marx had been to Roedean, and Cecilia Dunbar Kilburn had the wherewithal to travel to India, Burma and Siam. The fact that such women knew languages and were well travelled makes the insularity of Ravilious and Bawden in particular striking. Both won scholarships to visit Italy but returned unimpressed.

The perfectly delineated worlds that Ravilious and his peers created may have been a defence. In a period of social unrest and political extremism, most of Ravilious’s circle offered resolved imagery in which England was portrayed as a tidy garden, at once Georgian potting shed and precious stone set in a silver sea. The pre-industrial past held sway: folk art was important to Marx, while the rural crafts were captured in drawings and paintings by Bawden’s friend Thomas Hennell. Peggy Angus was more politicised, but even she prettified the USSR in sketches made on a visit in 1932. Her cheerfully squalid base below the Sussex Downs was memorialised in Ravilious’s Tea at Furlongs, an exercise in elegant excision. To simplify and idealise may have kept Ravilious’s demons at bay, reparation for what his wife, Tirzah, saw as his ‘rather frightening working-class world’. Dunbar Kilburn, who in the late 1930s set up a shop, on the other hand saw beauty as naturally residing in the 18th century. Her enterprise, Dunbar Hay, offered modernism through that filter. She granted Ravilious a retainer and he designed neo-Regency dining chairs for her and collaborated with Tom Wedgwood, whom Dunbar Kilburn persuaded to revive 18th-century shapes and put ceramic carpet bowls into production.

On the weekend before war was declared in September 1939, Ravilious was playing at bowls – or rather boules – on the lawn of Serge Chermayeff’s exquisite modern movement house, with its peerless view of the South Downs. Members of Ravilious’s circle, like all artists, faced immediate hardship, alleviated only by the War Artists Advisory Committee. Ravilious, Freedman and Bawden became official war artists and all exhibited great bravery. Bawden found himself in a lifeboat off the African coast after a torpedo attack on the ship he was travelling on. Ravilious produced some of his finest work during the conflict, although, characteristically, the horror of war is only suggested obliquely in his haunting Arctic watercolours. Nash, by then frail with asthma, gave us one of the greatest paintings of the war, Totes Meer, without leaving these shores. Perhaps strangest of all, William Rothenstein, long retired from the RCA and in poor health, began a series of drawings of pilots. As his son John recalled, ‘this small figure, mentioned in the “Goncourt Journals”, the familiar of Verlaine, Pater and Oscar Wilde, was out over the North Sea in a Sunderland flying boat.’

As for the women artists in the circle of friendship, Binyon joined the Ministry of Information and after the war taught at Bath Academy of Art at Corsham Court. Marx worked for the Recording Britain scheme, produced the children’s book Bulgy the Barrage Balloon and in 1944 was appointed a Royal Designer for Industry. Tirzah Ravilious struggled heroically with illness and three small children. In September 1942 she learnt that a plane carrying her husband had gone missing over the seas around Iceland. Shortly before her own early death in 1951, having happily remarried, she produced a remarkable series of paintings depicting an imaginary world of toys, plants and children. Andy Friend’s moving book ends with an illustration of Tirzah’s The Springtime of Flight, a recollection of tranquillity, showing grass, spring flowers and a butterfly from a child’s perspective, a fragile biplane flying overhead.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In fact, anyone handwringing about the current state of children's fiction can look at over 20 years' worth of my children's book round-ups for @Lit_Review, all FREE to view, where you will find many gems

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Philip Womack

literaryreview.co.uk

Juggling balls, dead birds, lottery tickets, hypochondriac journalists. All the makings of an excellent collection. Loved Camille Bordas’s One Sun Only in the latest @Lit_Review

Natalie Perman - Normal People

Natalie Perman: Normal People - One Sun Only by Camille Bordas

literaryreview.co.uk

Despite adopting a pseudonym, George Sand lived much of her life in public view.

Lucasta Miller asks whether Sand’s fame has obscured her work.

Lucasta Miller - Life, Work & Adoration

Lucasta Miller: Life, Work & Adoration - Becoming George: The Invention of George Sand by Fiona Sampson

literaryreview.co.uk