Tanya Harrod

She Carved Her Own Way

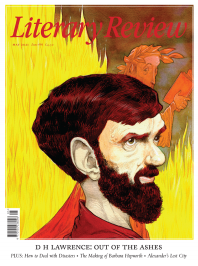

Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life

By Eleanor Clayton

Thames & Hudson 288pp £25

Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore.

Hepworth’s turn to sculpture was in itself not so unusual – female sculptors like Dora Gordine and Kathleen Scott were a force between the wars, if subsequently overlooked. In 1925 Hepworth married a fellow RCA student, John Skeaping. Together they took lessons in marble carving in Rome from Giovanni Ardini, a skilled craftsman then working for the acclaimed Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović. Both initially carved stylised birds and animals, having already attracted the interest of discerning collectors like Edward Marsh and George Eumorfopoulos. In 1928 Hepworth had a successful joint show with Skeaping at the Beaux Arts Gallery, which included an austere woman’s torso in Hoptonwood stone, now in the Tate. In 1931 she met and began an affair with Ben Nicholson. She divorced Skeaping in 1933.

By then she was making challenging, stripped-down semi-abstract works and, like Moore, had become associated with so-called ‘direct carving’, which had been pioneered before the First World War by Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Eric Gill. But being an ambitious female artist working in the avant-garde was far from easy. Her art was relentlessly analysed by male art critics. She was described as a sculptress, which she disliked, and worse; her work was found variously to be feminine, cold and artisanal. Innovatory practice became an issue – who made the first hole, the first oval form, the first string sculpture – and Hepworth was often cast as an acolyte of Henry Moore or of the Russian émigré Naum Gabo. She was consistently and unfairly on the receiving end of diminutions, encapsulated in a remark made by Henry Moore after her death. But for his influence, he reflected, ‘she would have become a drawing teacher at a secondary school’. He proved more a rival than a friend.

Hepworth’s work has received increasing and deserved recognition but her life has until relatively recently been off limits to researchers. Sally Festing’s unofficial 1995 biography was written without access to the sculptor’s archive. The understanding was that her son-in-law, the late Sir Alan Bowness, was writing a definitive study. Researchers on Hepworth were forced to operate round this lack of access, though the Bowness book never materialised. Eleanor Clayton’s Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life, published to mark a major retrospective at the Hepworth Wakefield, has, however, made full use of Hepworth’s papers, all now available in the Tate Archive. Clayton’s book is described as a biography. It is a description that does this finely written study a disservice. She has taken the decision not to round out Hepworth’s social and artistic circle, none of whom are granted the little pen portraits we associate with biography. Faced with the tide of garishly colourful insights that has accompanied recent biographies of Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, we have reason to rejoice at what appears to be an act of benign self-censorship.

For instance, Norman Capener, the surgeon who seems to have been a rock-like figure as Hepworth’s marriage to Ben Nicholson fell apart, is barely mentioned, while fascinating individuals like the communist crystallographer J D Bernal are barely characterised. The sheer toughness of life with the elusive Nicholson, before, during and after their marriage, is not dwelt upon. The artistic squabbles within the St Ives artistic community go undiscussed. The book echoes the brave cheerfulness of Hepworth’s own Barbara Hepworth: A Pictorial Autobiography, first published in 1970. Despite its odd scrapbook-like quality, the Pictorial Biography remains an important source for understanding Hepworth. It has since been augmented by Penelope Curtis’s brief but insightful Barbara Hepworth of 1998 and by Hepworth’s granddaughter Sophie Bowness’s Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations of 2015, a beautifully edited selection of Hepworth’s public writings and utterances.

Clayton’s book may be unusual in that she avoids the British biographical tradition of combining amateur psychoanalysis with elevated gossip. But it is perfect on its own terms, dissecting Hepworth’s thoughtful writing, the technicalities of her changing sculptural practice, the demands of motherhood and her ambition and seriousness. What emerges most powerfully from Clayton’s study is the importance of female friendships and loyalties in Hepworth’s life. The art critic E H Ramsden, who lived in a loving partnership with the archaeologist and art historian Margot Eates, was a constant support, as was the composer Priaulx Rainier. Rainier, for instance, reinvigorated Hepworth’s interest in music, helped to plant out the garden of her St Ives studio and was, despite bouts of depression, an inspiring companion. Clayton does not entirely give us Hepworth’s private (as opposed to public) persona, but she makes creative use of Hepworth’s letters to Margaret Gardiner, a most discerning patron whose significant wealth was employed tactfully and helpfully. Gardiner appears to have been Hepworth’s closest friend, with whom she could discuss her greatest sorrows and joys, as well as the pleasures of the day-to-day.

In Clayton’s account, these sustaining friendships went hand in hand with a kind of grand loneliness. Hepworth’s shy aloofness contrasted markedly with Henry Moore’s accessible ambassadorial bonhomie. And there was a solemn grasping for perfection in her work, in the causes she espoused (such as nuclear disarmament and social democracy), in her idealistic hope for a future in which technological progress would unite with the arts and in her championing of rational architecture and public sculpture. Her personal religiosity was mirrored in the thinking of Dag Hammarskjöld, the second secretary-general of the United Nations, who became Hepworth’s friend (almost soul mate) in the late 1950s. Hepworth gave him one of her purest sculptures, Single Form. He wrote a poem about it, which was found on his bedside table after his untimely death.

Hepworth could appear remote. Her determination not to be dragged down by everyday concerns was perhaps linked to her upbringing as a Christian Scientist. This was pre-eminently a belief system rooted in denial. As a framework for living, it was never entirely relinquished by Hepworth, even though she sensibly sought medical help for herself and her children when needed. Clayton could have said more about Hepworth and Christian Science and how it shaped her strategies of self-preservation. In the early 1950s, for instance, Hepworth tellingly explained to Rainier, ‘I have never made any secret of the fact that I avoid (evade) emotional reactions.’ But Clayton’s splendid book – a kind of anti-biography – succeeds by honouring her subject’s commitment and discretion, qualities that give Hepworth’s own work its enduring power. We are left with the sculpture – from her subtle Torso of 1932, in which a female form metamorphoses from a pillar of tropical hardwood, to her Cosdon Head of 1949, carved from ‘a singularly intractable’ piece of blue marble, its multiple viewpoints fusing abstraction and figuration, to her public tribute to Hammarskjöld, her 21-foot-high bronze Single Form (1961-4) outside the UN Secretariat in New York: an abstracted torso, a profile with an eye, a hopeful waymarker for a humanitarian future.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk