John Banville

Scoundrel Manages to Keep his Secrets

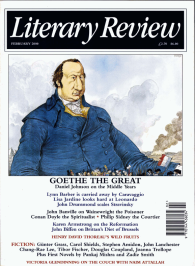

Wainewright The Poisoner

By Andrew Motion

Faber & Faber 320pp £20

God help the hangers-on, the small fry who desperately dart and flash amidst the barracudas and the killer whales. Life is hard at that level, even if you look like a big fish to the crustaceans on the seabed, or, at times, to yourself. It is almost possible to pity poor Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, painter and poetaster, who swam among the greatest of his day and ended up transported for life to the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania. The charge against him was forgery, but that was probably the least of his crimes. He had also conspired to defraud half a dozen insurance companies, and may well have poisoned not only the sister-in-law who was his henchwoman in the insurance seam, but her mother, too, as well as his own uncle, a man who in his lifetime had shown the ungrateful nephew nothing but kindness.

Wainewright has already been the subject of a number of biographies and novels, among them Bulwer-Lytton’s now forgotten Lucretia (1846); and also of a superb and urbanely subversive essay, ‘Pen, Pencil and Poison’ (1891), by Oscar Wilde. As Andrew Motion points out, many commentators have remarked the similarities between Wainewright and Wilde: both aesthetes, both dandies, both stars that fell from the zenith of fashionable artistic life to the lowest depths of disgrace and imprisonment; however, while Wilde had the true artist’s inability to tell anything but the truth (no matter how ambiguously), Wainewright was a born liar, and had not a fraction of Oscar’s vast talent.

Thomas Wainewright was born in 1794. His mother died early, and his father handed the child into the care of his maternal grandfather, Ralph Griffiths, who was editor of the influential Monthly Review, friend to luminaries of the day including Josiah Wedgwood, and publisher of, among others, Oliver Goldsmith, who reviewed for the magazine, and John Cleland, from whose notorious novel Fanny Hill Griffiths made a cool £10,000. The profits came in useful when he was building Linden House, his home in Chiswick. This fine mansion became part of the rich inheritance that Thomas Wainewright was to squander.

As Andrew Motion has it, Wainewright ‘lived half his life close to the centre of the Romantic revolution’. He was educated by the classicist Charles Burney, son of the great musicologist, and later studied painting with two of the best-known artists of the time, John Linnell and Thomas Philipps.

… he painted Byron’s portrait, and exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy during the early 1820s; he was good friends with Henry Fuseh, William Blake and Charles Lamb; he knew John Clare, William Hazlitt, Thomas de Quincey, Barry Cornwall and John Keats; he wrote art criticism for the London Magazine in its heyday; he was famously ‘amiable’, ‘kind’ and ‘good-hearted’ -silver-tongued, and a tremendous dandy.

As well as leaving Wainewright his house, Grandfather Griffiths put £5,000 worth of stocks into trust for him, to be administered by two of Wainewright’s uncles and a cousin, Edward Foss, the man who in time would be his nemesis. In 1822, chafing under the restrictions on his inheritance, and being in straitened circumstances, Wainewright hit on the expedient of forging the three trustees’ names on a bank draft for half the money, and on another draft the following year for the remainder. The Bank of England did not discover the fraud until 1835.

Wainewright quickly squandered the money, with the help of his wife, the enigmatic Eliza (did she know of the fraud, and of subsequent crimes, or was she an unwitting accomplice?), and before long the bailiffs were in. At this time, Wainewright’s mother-in-law, a Mrs Abercrombie, and her two daughters, Helen and Madeleine, moved in to live with the Wainewrights at Linden House. Very soon, Mrs Abercrombie died, mysteriously and in convulsions of agony. Wainewright was suspected of having poisoned her, although it is hard to see a motive, since he did not benefit financially from her death, and even such a one as Wainewright surely would not have resented a live-in mother-in-law that bitterly.

By now desperate for money, Wainewright devised a scheme whereby Helen would take out multiple insurance policies on her life, after which the Wainewrights, along with Helen and her sister, would abscond to France, where presumably Helen’s death would be faked, Wainewright and Eliza would collect the money, and all would live happily ever after. It did not work that way. Instead, Helen also conveniently died (in convulsions, as her mother had), after two successive nights on the town with Wainewright, who had made sure that the poor girl consumed much seafood washed down by porter, so that there would be something on which to blame her death. The insurance companies, smelling a rat, refused to pay up.

Now Wainewright fled to France, where he spent five years living by his wits. In May of 1837 he returned to England, and was promptly arrested and tried for forgery, a capital offence at the time. After a bit of plea bargaining, he agreed to plead guilty on the promise of leniency; either he was betrayed, or the judge considered transportation a lenient sentence. In Tasmania, he was put to work road-building, and later as a hospital orderly, until he was eventually given a conditional pardon and allowed to take up his brushes again, painting portraits of a number of Hobart worthies. He died in 1847, by some accounts ‘a man of superior attainments’, by others an embittered misanthrope. Perhaps the most accurate judgement was that delivered by Agnes Power, whose husband had sat for one of Wainewright’s Hobart portraits: ‘He certainly was a wonderful man, full of talent and fuller still of wickedness.

It is a splendid story, with many puzzles and lacunae, and Andrew Motion has chosen to tell it by a fittingly oblique method. Instead of a straightforward biography, he gives us Wainewright’s first-person, fictionalised ‘confession’ – a document as circumspect, slyly reticent, and oleaginously smooth as the man himself-and adds extensive notes at the end of each chapter to amplify Wainewright’s account, and frequently correct it. The faint tone of defensiveness in Motion’s foreword is an indication of the riskiness of the enterprise. One applauds his courage, and admires his inventiveness, but the trick does not quite come off. Wainewright is not vividly alive enough in the ‘confession’ to convince the reader, and the constant interruption of the chapter-end notes is a distraction. In the end, Wainewright remains the scoundrelly enigma he always was: a state of affairs which would surely have pleased him greatly.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk