Jay Parini

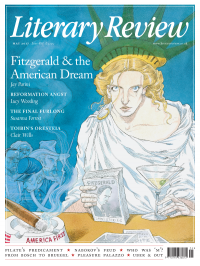

Tender Is the Writer

Paradise Lost: A Life of F Scott Fitzgerald

By David S Brown

Harvard University Press 413pp £23.95

I’d Die for You and Other Lost Stories

By F Scott Fitzgerald (Edited by Anne Margaret Daniel)

Scribner 358pp £16.99

F Scott Fitzgerald is the most irresistible of modern American writers, and readers return to his pages time and again. When Paradise Lost landed on my desk for review, I had just, over the past year, read through Fitzgerald’s major novels and stories, work I’ve known and admired for half a century. But classic literature is, in Pound’s great phrase, ‘news that stays news’, and I continue to read Fitzgerald as compulsively as I read the daily headlines.

The problem with Fitzgerald has never been the work; it’s been the writing about him. The standard biography for some time has been Some Sort of Epic Grandeur, a 1981 study by Matthew J Bruccoli. It’s a reliable and boring compilation of facts, not as well written as the first major assessment of the life and work, The Far Side of Paradise by Arthur Mizener (1951). Any number of lives of Fitzgerald have appeared over the decades, but I’ve not found them satisfying, in large part because they tend to portray the author as a spokesman for the so-called Jazz Age, a drunken playboy with unresolved aspirations who embodies the empty morality of the Lost Generation. One got more by reading memoirs of the period, such as Malcolm Cowley’s haunting Exile’s Return (1934), which recalls well-known American authors in Paris in the 1920s, a kind of golden age that continues to inspire young American writers to travel abroad to seek their imaginative fortunes. Fitzgerald was hardly celebrating the lifestyles of the rich and famous. Instead, he offered a rueful and remorseless critique of that world, however much he adored it.

Fitzgerald was a good Catholic boy by training, a young man who read the Gospels and understood (though he resisted the notion, almost successfully) that it’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter heaven. His wealth-bedazzled characters, including Jay Gatsby, Amory Blaine in This Side of Paradise and Gordon Sterrett in ‘May Day’, that incomparable early masterpiece of short fiction, find little pleasure in their lives. They have swallowed a notion of the American Dream that has turned into a kaleidoscopic fantasy which tantalises but never quite resolves into a steady image. There is no fun in their yearning for something they can’t possess and that nobody can ever have. Satisfaction doesn’t come with things, however beautiful and plentiful. Tender Is the Night (1934) is, perhaps, unequal to the poetic ferocity and compression of The Great Gatsby (1925), but its sensitive hero, Dick Diver, is the most heartbreaking of Fitzgerald’s characters, a man with everything and nothing. This episodic, gorgeously written novel tracks the author’s own decline from the mid-1920s through to the Great Depression, which became an external correlative to Fitzgerald’s own spiritual (as well as financial) bankruptcy.

What I admire about Paradise Lost is that it moves well beyond the hackneyed images in which the author lives in the prison house of his own fragile dreams, a sybaritic social climber who squanders his talent by drinking. For David Brown, ‘Fitzgerald sought to record in some definite sense the history of America’, with its dream of equality and liberty for all ruined by unchecked capitalism. Brown writes: ‘The growing power of industrialists and financers offended his romantic sensibility, and he wondered if this rising republic of consumers could ever recover its old idealism.’

This biography seems wildly relevant in a time when raw wealth has again taken on such an emblematic value. We’re awash in capital, but it flows only to the wealthiest among us, who often seem as useless as Tom Buchanan himself, described by Nick Carraway in Gatsby as ‘a sturdy straw-haired man of thirty’ with ‘arrogant eyes’ and ‘a cruel body, gruff and aggressive’ (this may remind you of someone). One is taken back to the brilliant early story ‘The Diamond as Big as the Ritz’, which retains a mythic quality in its portrait of wealth run amok, a morality tale about the deadly consequences of greed. ‘This is where the United States ends,’ writes Fitzgerald in the story.

More than any biographer before him, Brown reveals the degree to which Fitzgerald understood the politics of his era, and he positions him in the company of Progressive intellectuals, such as Randolph Bourne and Charles Beard, who understood that with massive waves of immigration from southern and eastern Europe, Ireland and elsewhere, the USA had begun to drift from its puritanical anchorage.

As he should, Brown writes with fitting excitement about the glory years, when Fitzgerald rode high in American letters, the young man of the day who married the fabulous bride and took off with her for Europe with money in his pockets and dreams to burn. There was lots of money, in fact, as his first novel, This Side of Paradise, sold over fifty thousand copies in 1920, its first year, and the Saturday Evening Post and rival magazines paid the author handsomely for his stories, which poured out of him at a terrifying pace. Fitzgerald himself understood that this early success could not be sustained. For a time Fitzgerald and Zelda, his flamboyant, gifted wife, were caught in the whirlpool of greed and extravagance that characterised much of the 1920s, and it eventually sucked Zelda into madness and led to the break-up of a marriage that had meant so much to Scott, who idealised her as belonging to a higher class, the daughter of a judge in Alabama, a true Southern belle (that vision of her was, as Brown shows, delusional).

I’d Die for You and Other Lost Stories is a new collection of (mostly) late, discarded stories by Fitzgerald that has been nicely collected by Anne Margaret Daniel. We faintly see where he might have gone, had circumstances differed. But he needed money and fled to Hollywood, where studios paid him $1,000 per week as a script doctor. (He added material to Gone with the Wind, among other films, although this writing amounted to very little.) The money helped to pay for his wife’s care in a mental institution in Alabama and for his daughter’s schooling, as well as abetting his own natural profligacy. In a letter to Zelda, written shortly before his death in 1940 at the age of forty-four, he reflects on the decline of his popularity: ‘I think the nine years that intervened between The Great Gatsby and Tender hurt my reputation almost beyond repair because a whole generation grew up in the meanwhile to whom I was only a writer of Post stories.’ He wonders whatever happened:

It’s odd that my old talent for the short story vanished. It was partly that times changed, editors changed, but part of it was tied up somehow with you and me – the happy ending. Of course every third story had some other ending but essentially I got my public with stories of young love. I must have had a powerful imagination to project it so far and so often into the past.

What propels these late stories, many of them incomplete or offered in draft versions, is a profound alertness to the American decline, which he wisely traces (in two remarkable tales) back to the Civil War. ‘Thumbs Up’ and ‘Dentist Appointment’ contain some of the most vivid writing to be found here, though anyone in love with Fitzgerald will find other treasures, including the poignant title story, which deals with a sad period he spent in the mountains of North Carolina in the 1930s, where he hoped to improve his health. The Civil War stories are variants of the same tale, later condensed and published in a different form as ‘The End of Hate’, which appeared in Collier’s in 1940. Fitzgerald hoped to write a Civil War novel some day. One wishes he had lived to see this happen.

It’s easy to dismiss posthumous collections of discarded scraps from a major author as yet another attempt by the estate to capitalise on that author’s fame, but Fitzgerald’s imagination never ceased to boil and this writing, however unfinished at times, enhances our sense of his later years and how he coped with decline.

As Brown further suggests, Fitzgerald’s awareness of being part of an entire nation in decline was acute: ‘The long run of laissez-faire individualism – defined variously as rule by a robber baron, a titan, or, as Fitzgerald would have it, a tycoon – had come to an end.’ As ever, his own story mirrored that of the nation and one comes away from these books, a splendid biography and a useful gathering of fragments, to see Fitzgerald for what he was: a deeply gifted writer with an excited if not overwrought imagination who looked into the sad American abyss of his time and saw, however imperfectly, its future.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Delighted by this review from @alexander_c_lee in @Lit_Review, and his excellent insights about the challenge set by Pico's thought. Finding the right reader is a book's greatest blessing.

Out now! Literary Review's February 2025 issue, featuring

Ritchie Robertson on W G Sebald

@francisbeckett on miners

@nclarke14 on the colour pink

@TheoZenou on the Pope

Michael Burleigh on Huawei

and much, much more:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

In the Current Issue: Peter Marshall on the Peasants' War * Philip Snow on Hiroshima * Jonathan Sumption on free...

literaryreview.co.uk

Two great bags for your books. Our Literary Review tote bags feature an illustration of our beloved, book-filled office on Lexington Street. Only £10 (lightweight) or £15 (sturdy) at our online shop

http://literaryreview.co.uk/shop