Gillian Tindall

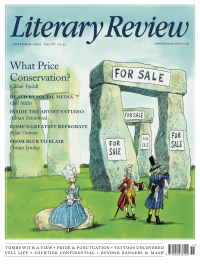

To Preserve or Not to Preserve?

Heritage: A History of How We Conserve Our Past

By James Stourton

Apollo 496pp £40

In the comprehensive introductory chapter to his huge, energetic and tightly written tome on the two-and-half-century history of conservation battles in our homeland, James Stourton quotes museum director Roy Strong’s celebrated remark that concern for heritage is what has today replaced regular attendance at morning service. Maybe so, but it is equally the case that, just as religious practice over the centuries has been the object of much furious argument, so the battle over what to retain of what we have inherited and what to replace is one that is fought passionately by each successive generation.

Rows about preservation go back much further than present-day defenders of the green belt, conservation areas, well-liked local buildings or precious paintings may realise. It was in 1779 that the political firebrand John Wilkes lobbied Parliament to buy Catherine the Great’s picture collection from Houghton Hall for the nation rather than letting it be dispersed. In 1825 Stonehenge was sold by one grand family to another; not until the very end of the century was it openly recognised that ‘there is something absurd in the idea … that Stonehenge should be at the mercy of a private person’. In 1871, a Liberal MP, Sir John Lubbock, alerted by a local vicar that the stone circles of Avebury were about to be destroyed to create a housing estate, had to purchase Avebury Mound as a matter of emergency in order to preserve the site.

It was Lord Spencer’s attempt to enclose Wimbledon Common in 1864 that awoke both population and government belatedly to the number of commons that had been lost to the public in the

preceding seventy years. The Commons Preservation Society was founded in response (indeed each of the crises mentioned above brought about the creation of some body, governmental or voluntary, responsible for preservation). The attempted takeover of Parliament Hill Fields by a local landowner (who was, legally speaking, acting within his rights) came to the attention of various prominent figures, including Octavia Hill. The resulting campaign ensured that Parliament Hill Fields was incorporated into Hampstead Heath. The threatened loss of John Evelyn’s garden in Deptford in the 1880s was the catalyst for the creation of the National Trust. While ancient churches around the country were being over-restored and William Morris was having a stand-up row about it with the vicar of Burford, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings was born. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the British Archaeological Trust, the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Council for the Preservation of Rural England and many other local bodies have been founded, developed, reconstituted and given more – and often, particularly over the last twenty years, less – government money and support.

But formal bodies and committees do not necessarily move fast enough to avert new crises. Again and again in the story of preservation in this country, we find that a handful of dynamic and determined people managed to save some part of our habitat that would otherwise have become no more than a fading memory. In this, the British tradition of volunteerism has stood us in good stead, though Stourton makes the point that the more bureaucratic continental countries introduced state protection of heritage rather earlier than us. Good or bad? Jocelyn Stevens, on ceasing to be chairman of English Heritage in 2000, remarked that saving heritage was a continuous battle and that central government was one of its ‘deadliest enemies’.

A major problem, of course, is that concepts of what is worth saving change and expand with each passing generation. From the earliest days of Wordsworthian concern for the untouched Lake District right up to the 1940s and Patrick Abercrombie’s plans for postwar Britain, the countryside and country houses were perceived to be most in need of protection. This was our ‘green and pleasant land’; townscape was pathologised as somehow ‘unnatural’ or even ‘sick’. But, as the late and much-missed Gavin Stamp pointed out, ‘the history of conservation has been the art of keeping one step ahead of public opinion.’

Personally, although I cannot forgive Abercrombie for his Greater London Plan, which resulted in the unnecessary destruction of London’s East End (much of which, contrary to modern myth, had not been destroyed in the Blitz), I do recognise that he was a good person in his time. All conservationists are inevitably partial in their endeavours. Although the late Sir John Summerson was the pre-eminent 20th-century authority on Georgian architecture, his lack of enthusiasm for Victorian styles actually led him to favour the demolition of St Pancras Station, a viewpoint that seems shocking today. As for Richard Crossman, the Labour minister of housing in the 1960s who expressed himself in favour of pulling down the terraces of Islington, I was glad and interested to learn from this book that, when he saw much of Liverpool being destroyed, he experienced a Damascene conversion and henceforth attempted to prevent the particularly crass council of that city from doing its worst.

That local authorities in general do not come well out of Stourton’s survey will not surprise many who have fought conservation battles. The granting by councils of permission for the erection of a tall building, representing ‘investment’ in lucrative office space, is often the prelude to the destruction of whole skylines. This has happened most notably in the past twenty years in the City of London. As Stourton notes, although few venerable buildings have been destroyed there, ‘we have reached the limit of what this fragile area can take’. In particular, the ‘belittling of St Paul’s and the Tower of London remains a serious loss’.

Stourton devotes much space, rightly, to the huge threat to heritage posed by the twin postwar obsessions with rebuilding, including the rebuilding of cities that did not in fact need it, and fulfilling the demands of the private car, which were imagined to be irresistible. He is wonderfully knowledgeable on England, less so on some outlying parts of Britain, and I would have liked a few more compare-and-contrast paragraphs on foreign capitals. He tells us – I did not know this – that in 1894, following the wishes of Queen Victoria, a height limit of eighty feet up to the parapet was imposed on London buildings. Had we continued to respect this, London today would be a no less busy but a far more homogeneous and coherent city. The reason I know this is that Paris has actually evolved along these lines. When, in the 1970s, President Pompidou destroyed the medieval Marais, turned the quays of the Seine into a motorway and declared it his aim to ‘Manhattanise’ Paris, there was considerable disquiet. However, Pompidou died of leukaemia while in office and the president who took over, Giscard d’Estaing, brought in regulations designed to keep Haussmann’s Paris substantially intact, as it remains to this day.

I suspect that Heritage was written during lockdown and has been waiting its turn to be published. Significant facts that could have been incorporated within the text have been put in the footnotes, a sign of pre-publication tinkering, including information about the valiant, last-moment saving of Spitalfields houses in the 1960s by determined occupiers, some of them still living there today. But this is a minor quibble about a masterful, dynamic and extremely readable survey of one the major issues of our times. Or all times.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Under its longest-serving editor, Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair was that rare thing – a New York society magazine that published serious journalism.

@PeterPeteryork looks at what Carter got right.

Peter York - Deluxe Editions

Peter York: Deluxe Editions - When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines by Graydon Carter

literaryreview.co.uk

Henry James returned to America in 1904 with three objectives: to see his brother William, to deliver a series of lectures on Balzac, and to gather material for a pair of books about modern America.

Peter Rose follows James out west.

Peter Rose - The Restless Analyst

Peter Rose: The Restless Analyst - Henry James Comes Home: Rediscovering America in the Gilded Age by Peter Brooks...

literaryreview.co.uk

Vladimir Putin served his apprenticeship in the KGB toward the end of the Cold War, a period during which Western societies were infiltrated by so-called 'illegals'.

Piers Brendon examines how the culture of Soviet spycraft shaped his thinking.

Piers Brendon - Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll

Piers Brendon: Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll - The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West by Shaun Walker

literaryreview.co.uk