Tim Stanley

Tricky Questions

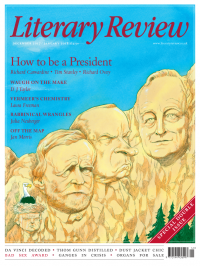

Richard Nixon: The Life

By John A Farrell

Scribe 737pp £30

Richard Nixon was a bad man but an effective conservative – a conservative not in the ideological sense (cutting taxes, throwing bums off welfare) but in the sense of a statesman who tries to navigate his country through choppy waters and bring it out the other side afloat. The Watergate Scandal eclipsed his achievements, but the achievements are many.

As John A Farrell shows in this new biography, the 37th president took over a country that felt like it was on the brink of civil war. We talk about our troubles today as if they were unique: America had them in the 1960s one thousand times over. Kids were dying in Vietnam for a war that seemed to have no purpose and no end. Racism was endemic and violent. In 1968, the year of Nixon’s narrow election victory, both Martin Luther King Jr and Robert F Kennedy were shot dead. Nixon’s critics greeted his win as a betrayal of liberal promise. His supporters prayed it would prove a remedy to the chaos left by the liberals.

The accepted narrative, bolstered by historians such as Rick Perlstein who assign Nixon a critical role in the Republican Party’s long journey from elite club to Trumpite populism, is that Nixon chose not to end America’s culture war but win it. Split the country in two, his adviser Pat Buchanan said, and the Republicans will get the larger half. There’s no denying that Nixon did this. He defined even his fairest critics as ‘enemies’, whipped up public anger and used a mix of political pressure and dirty tricks to defeat them. He appealed directly to the ‘great Silent Majority’ with the promise of law and order. His campaign to woo Southern whites was a mix of sly hints and theatre. At a dinner for journalists in 1970, Nixon and his vice president, Spiro Agnew, who was put on the Republican ticket in part because civil rights activists hated him, appeared on stage seated at two pianos. Nixon would start to play tunes such as ‘Home on the Range’ and the ‘Missouri Waltz’ – and his vice president would drown him out with a chorus of ‘Dixie’. Agnew was Nixon’s hatchet man. The vice president’s campaign against the press, which he called ‘a tiny and closed fraternity of privileged men, elected by no one and enjoying a monopoly sanctioned and licensed by government’, was every bit as virulent as Donald Trump’s. Trump threatens press freedom; Farrell accuses Nixon of actually trying to take it away. In 1971, his administration urged the federal courts to prevent a newspaper from publishing leaked documents – the first time in history that the US government demanded ‘prior restraint’.

What motivated Nixon? Electoral calculation, for sure. Pure bigotry, undoubtedly. A lot of journalists and liberals were Jewish, something he never tired of pointing out to his members of staff, even if they happened to be Jewish themselves. ‘The government is full of Jews,’ he told his chief of staff, ‘most Jews are disloyal.’ He told his aides, ‘It is a part of the background, the faith and the rest … They always come down that way … you just can’t find any who don’t’, to which his attorney general replied, ‘Well at least the Supreme Court ruled yesterday that the Jews couldn’t get into our golf clubs.’ Nixon did credit Jews with intelligence, whereas blacks, he told a young aide called Donald Rumsfeld, are ‘just out of the trees’. And why were there so many gays on television? ‘I don’t even want to shake hands with anybody from San Francisco,’ the president said on another occasion. ‘Decorators. They’ve got to do something … but goddamn it we don’t have to glorify it.’

‘And yet’ is the phrase Farrell employs to indicate that there’s a paradox coming in his text. And there are many. Nixon, the man Hunter S Thompson described as ‘criminally evil’, established the Environmental Protection Agency, opened methadone clinics to treat drug addicts, ended the enforced assimilation of Native Americans, signed the Occupational Health and Safety Act, outlawed bias against women in school sports, became the first president to visit communist China, pursued arms control with the Soviets, sent arms to Israel during the Yom Kippur War, backed a prototype of Obamacare, ended the military draft and, in 1973, brought peace to Indochina. Some of Nixon’s most spectacular achievements were in the field of race relations. At the same time as he stoked the resentments of Southern whites, Nixon quietly effected the desegregation of the South’s public school system and established the first federal affirmative action programme. Given that education was the target of the US civil rights movement, there’s a case for saying that Nixon’s beneath-the-radar approach – backed by considerable personal diplomacy – triumphed where many righteous liberals had failed. By 1972, America was supposedly governed by a reactionary silent majority, yet in many senses was more progressive than it had been in the Swinging Sixties. The November presidential election suggested that Nixon, far from dividing his country, had united and pacified it. He won every state except Massachusetts. And he didn’t need that stupid burglary at the Watergate Complex to do it either.

The problem with any assessment of Nixon’s presidency is that Watergate was so great a catastrophe that it’s impossible not to see it as the ultimate indictment of the man himself. Farrell concludes that it was the president’s fault. His lack of self-confidence and his paranoia led him to surround himself with yes men willing to follow malicious orders to their bitter end. What the burglars were looking for in the Democratic headquarters at Watergate is still unknown, but their arrest uncovered a trail that led all the way to the Oval Office, where a tape system recorded the foul-mouthed Nixon’s plots and schemes. His attempts to resist a Congressional inquiry were as principled as they were about saving his own skin: he honestly believed that the integrity of the presidential office was at stake. And from that last battle was born one of the greatest Republican heresies of all: the view that the presidency, unlike Congress or the courts, is the true voice of the people, the directly elected embodiment of popular will at constant war with a liberal elite.

In that sense, Trump is Nixon’s heir. But there are also many differences. Trump might actually be less prejudiced than Nixon, yet Nixon was also very intelligent, sensitive (yes, really) and an internationalist. Whatever he said in private, he wanted to be acknowledged by history as an enemy of racial injustice. His statecraft belonged to the old school of conservatism that seeks to reconcile past and present and unite the nation around commonly held values. His heroes were Abraham Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson. His tombstone reads: ‘The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peacemaker’. As Farrell’s ambiguous biography shows, Tricky Dicky is still tricky after all these years.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Alfred, Lord Tennyson is practically a byword for old-fashioned Victorian grandeur, rarely pictured without a cravat and a serious beard.

Seamus Perry tries to picture him as a younger man.

Seamus Perry - Before the Beard

Seamus Perry: Before the Beard - The Boundless Deep: Young Tennyson, Science, and the Crisis of Belief by Richard Holmes

literaryreview.co.uk

Novelist Muriel Spark had a tongue that could produce both sugar and poison. It’s no surprise, then, that her letters make for a brilliant read.

@claire_harman considers some of the most entertaining.

Claire Harman - Fighting Words

Claire Harman: Fighting Words - The Letters of Muriel Spark, Volume 1: 1944-1963 by Dan Gunn

literaryreview.co.uk

Of all the articles I’ve published in recent years, this is *by far* my favourite.

✍️ On childhood, memory, and the sea - for @Lit_Review :

https://literaryreview.co.uk/flotsam-and-jetsam