Richard Carwardine

Warrior in the White House

Grant

By Ron Chernow

Head of Zeus 1,074pp £30

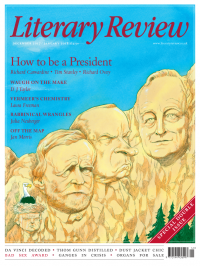

The ranking of American presidents by historians and political scientists is a much-loved exercise. Part of the fun is watching reputations rise and fall over time. Currently, even those who have long occupied the lowest places are on the move, since the 45th president, Donald J Trump, lifts all boats: the lamentable Civil War-era presidents James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson are each likely to rise a place, and so too the egregious Warren G Harding, who presided over a notoriously corrupt administration in the early 1920s. In recent years, no case of advance has been more striking than that of Ulysses S Grant, a two-term president who served from 1869 to 1877. After a century’s disparagement by snobbish critics such as Henry Adams, who thought him commonplace (‘the progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant’, the Bostonian wrote, ‘was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin’), the 18th president has found increasing favour, rising from bottom place in 1948 to a position now comfortably in the top half of the rankings.

This re-evaluation has to be seen in the context of a long charge sheet of indictments, above all that Grant, the boldest, most dynamic of Civil War military commanders (one whom Abraham Lincoln valued as the Union bulldog who would never shirk a fight), proved disconcertingly passive, even naive, as a political leader. Specifically, it is said that by putting his trust in unqualified and self-serving subordinates, including former military associates and members of his wife’s family, he left his administration prey to corruption. Most alarmingly, he served as an unwitting ally of two Wall Street buccaneers in their daring but unsuccessful attempt to corner the gold market. It was also alleged that a ‘Whiskey Ring’ of government agents, including the president’s private secretary, colluded with distillers to divert tax revenues – a charge given added colour by Grant’s personal struggle with alcoholism. In foreign policy, the president’s misguided attempt to annex the Dominican Republic split the Republican Party before the presidential election of 1872. During his second term, Grant watched the radical reconstruction of the former Confederate states, a plan dependent on African-American citizenship and a solid black Republican vote, succumb to the violent Southern revanchism of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists. Grant’s detractors have included both progressives appalled by his political and financial naivety and vengeful Southern white conservatives incensed by the acts of ‘the butcher’, who drenched the land in their brothers’ blood and oversaw the reintegration of the Confederate states into the Union on humiliating terms.

Ron Chernow’s Grant brings an eloquent voice to the ongoing work of rehabilitation. Only last year Ronald C White’s American Ulysses extolled Grant’s deep faith, sense of honour, commitment to racial justice and essential decency. But in Chernow’s hands Grant becomes an even more heroic figure. A prizewinning biographer with a gift for placing his American subjects in grand but intimate narratives (his Alexander Hamilton inspired Lin-Manuel Miranda’s stonkingly successful musical), Chernow takes as an emblematic starting point the final challenge of Grant’s life. Financially ruined by fraud in 1884, determined not to leave his family destitute and suffering from the onset of throat and tongue cancer (the legacy of lifelong cigar smoking), Grant agreed to write his memoirs. Racked with pain, the taciturn commander managed to complete, just days before his death in July 1885, a stunning literary masterpiece that has remained in print to this day. The talent it illuminated would have remained hidden but for this adversity. Chernow finds in this last great triumph of Grant’s life a metaphor for the ‘surprising comebacks and stunning reversals’ of his career as a whole. Sophisticates too easily underrated a plain, unassuming man with a rich but unobtrusive set of qualities: ‘a shrewd mind, a wry wit, a rich fund of anecdotes, wide knowledge, and penetrating insights’.

Throughout his rich, lively and well-paced narrative, Chernow develops a case against the ‘pernicious stereotypes’ that have dogged Grant’s reputation: the butcher, the drunk and the incompetent president. The first charge derives especially from the carnage on the battlefields of Virginia in the early summer of 1864, when the Union army suffered over fifty thousand casualties in thirty days through bloody engagements in the Wilderness and at Cold Harbor. Grant would always regret this, the deadliest of his costly frontal assaults. Yet his willingness to contemplate mass casualties stemmed not from bloodlust but from a strategic understanding – shared by Lincoln – that only by crushing the forces of the Confederacy in battle would the superiority of the Union be made to tell. The boy who was sickened by the blood and gore of his father’s tannery grew up to be a compassionate realist about the cruelty of war. His chief traits as a military leader were unusual self-possession and clear-headedness, even tranquillity, in battle, which from his first experience of war (in Mexico) gave him the capacity to assess the unfolding options quickly, manoeuvre swiftly and surprise the enemy. Few doubt that Grant was one of the great commanders of history.

Chernow accepts that Grant was an alcoholic but treats his solitary binge drinking as a disease, not as a personal moral failing – though that surely was how his own Methodist family judged it and was the lens through which he himself saw it. Serving in remote frontier garrisons following the Mexico campaign, separated from his wife and family, he was surrounded by heavy drinkers. It was easy to fall prey to a habit that would lead him to leave the army in 1854. Yet, persistent as the impulse would be throughout his life, equally evident was a sustained capacity for self-control. An advocate of the temperance pledge, during the Civil War he fiercely policed the abuse of alcohol in the Union camp, smashing liquor barrels and warning off peddlers of drink. Later, in the White House, there was little, if any, evidence of binges or even regular, modest imbibing. Chernow treats Grant’s pursuit of self-mastery as a heroic achievement, on a par with his military triumphs at Shiloh, Vicksburg and Chattanooga.

It is more difficult to agree with Chernow’s verdict that Grant was ‘an adept politician’ who occupied the presidential chair ‘with distinction’. To declare him personally innocent of corruption is fair and proper. To emphasise his consistently progressive stance on race – as a prewar opponent of slavery, a wartime liberator and a postwar defender of African-American rights – is to recognise a commitment that stands to his eternal credit. The scourge of the Klan, he oversaw the creation of the Justice Department, designed to undergird principled law enforcement in the former Confederacy; the presidential election of 1872 in the South was the fairest for African-Americans until the application of civil rights statutes a century later. In a similar vein, Grant sought a peace policy towards Native Americans that would incorporate them justly into the republic. Even so, resurgent violence in the South undermined and eventually broke Republican reconstruction during Grant’s second term, and – as Chernow recognises – the president’s well-intentioned Native American policy was vitiated by his tough action to defend westward-moving settlers and an unrealistic belief that nomadic Native Americans would willingly resettle on reservations. In going along with the conventional wisdom that Grant ‘could be surprisingly naive and artless in business and politics’, Chernow weakens his case for seeing Grant in quite the positive terms he encourages us to embrace. That said, Grant could not have wished for a better or more winning advocate.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

Give the gift that lasts all year with a subscription to Literary Review. Save up to 35% on the cover price when you visit us at https://literaryreview.co.uk/subscribe and enter the code 'XMAS24'