Claire Harman

Handbags & Handcuffs

The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective

By Sara Lodge

Yale University Press 366pp £20

‘If there is an occupation for which women are utterly unfitted, it is that of the detective,’ claimed the Manchester Weekly Times in 1888 – already behind the times, it seems, as women had been acting the part for years, albeit invisibly. They had started to feature in detective fiction too. It was studying the burgeoning market in ‘lady detective’ stories post-1860 that led Sara Lodge to wonder who the fantasy sleuths were modelled on, and why the Victorians found them so disturbing and alluring.

What she has uncovered is a vast network of women in police work who stayed beneath the radar, off the books and virtually undocumented until now. Who knew about ‘watchers’, doing surveillance on the streets, or ‘searchers’, frisking and handling suspected female criminals under arrest, or ‘writters’, working privately for solicitors and shadowing targets in order to serve writs on them? Apparently, there were hundreds. In an age when employment for women was both scarce and frowned upon, poor women flocked to obtain such work, which was casual, secret and exciting. And if you could look the part, that was all to the good: respectable-looking matrons were the best at serving writs, as they provoked least suspicion right up to the moment when they got a foot in the door. But it was often a risky business. Margaret Saunders, a freelance detective at Scotland Yard in the 1860s and 1870s, had molten lead thrown over her while going after a gang of coiners, and earned the nickname ‘Clubnose’ thanks to the injuries she sustained in the course of a long (and secret) career.

Women’s apparent guile and ability to deceive seemed to have found a professional outlet at last, especially in divorce investigations, leading an American journalist of 1878 to call lady divorce detectives ‘as unscrupulous as they are clever. They hesitate at nothing to procure the necessary evidence against or for the party. They will manufacture it rather than miss it, and incite to the very crime which they were paid to detect.’ This was certainly so in the Barrett divorce case of 1892. The respondent had been lured into adultery by two detectives employed by her husband. When the deception was exposed, the female detective involved was sentenced to a year’s hard labour. Nice girls didn’t go in for sleuthing, so it certainly seemed like an odd career choice in 1890 for Charlotte Williamson, a 24-year-old middle-class married woman, until it transpired that she was hoping to cover up her own extramarital affair with the head of the detective agency. The clue might have been her hanging a large portrait of her employer at the foot of the conjugal bed, something that provoked much merriment in court during her own divorce proceedings.

Female sleuths were seen as more emotionally committed to their cases than their ‘cool’ male counterparts, and possibly better overall, given their persistence and intuitive intelligence. The outspoken feminist Frances Power Cobbe proposed a female police force as early as 1888, saying it would be sure to outperform the male-only Met, and remarking that it was a pity there wasn’t one already in place to speed the capture of Jack the Ripper. She imagined a pack of Furies closing in on ‘the demon of Whitechapel’, aided by the bloodhounds recently co-opted into the force – a perfect vision of poetic justice. Meanwhile, some male officers tried to gather evidence against the Ripper by going undercover in drag in the East End, but were assaulted by passers-by. ‘Such fiascos tended to emphasise the point that actual women were needed,’ Lodge says drily.

The sleuth heroines of fiction also relied on ingenuity rather than brawn and often had modest-seeming outer lives: Anne Rodway was a seamstress detective; Dora Myrl was an amateur, speeding after thieves on her bicycle; Susan Hopley exposed a swindle in a draper’s shop. Stories involving female detectives were popular and imaginatively enabling, yet, as Lodge says, ‘like many fantasies of empowerment, they also gloss over the everyday realities faced by women detectives working in the streets’. Fact and fiction met in the case of Kate Warn, overseer of the female employees of Pinkerton’s Detective Agency in the 1860s, who became a posthumous celebrity and poster girl for early American feminists, mostly on the strength of a heavily fictionalised obituary written by her former boss. Pinkerton made her sound like some sort of crinolined action hero, foiling a gang of bank robbers single-handed, outwitting and outsmarting dangerous criminals through cunning and disguise, and even saving Abraham Lincoln, yet to become president, from an assassination plot on a train from Baltimore to Washington. But Lodge has done some impressive detective work of her own here, going over the printed sources and finding many manuscript ones. She comes to the conclusion that Pinkerton, a renowned self-publicist (and also probably Warn’s lover), was almost undoubtedly inventing or inflating the whole damn thing to promote his business.

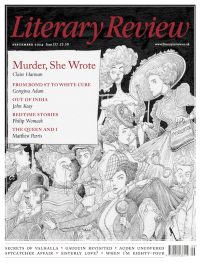

There was a definite frisson to all this role-swapping and gender-thwarting stuff, and publishers were quick to exploit it. Revelations of a Lady Detective (one of the very first ‘lady sleuth’ books) had a cover with an extremely ooh-la-la image of a woman with a knowing look lifting her skirt to show an ankle (a suggestiveness which didn’t feature in the actual stories), while the very idea of a mould-breaking heroine made ‘lady detective’ shorthand for all sorts of unusual behaviour. In 1888, a man charged with striking and threatening his wife offered the defence that he had been provoked by the persistent presence of a Miss Flynn, who had moved into bed with his wife and was now lounging around the house ‘in a semi-nude state’, smoking cigars. When it was her turn on the witness stand, Miss Flynn claimed ‘in a loud tone of voice’ that she was simply ‘a female detective’.

I imagine that Miss Flynn and her piquant little courtroom joke came to Lodge’s attention courtesy of the extensive digitisation of 19th-century newspapers and magazines, the assistance provided by which Lodge acknowledges warmly in her introduction. Anyone who has used the databases will understand her gratitude and awe: you go in search of one thing and find… everything. It turns research into a gloriously entertaining journey down a rabbit hole. Sara Lodge has marshalled the treasures of her research with enormous skill and style, producing a book of true importance, a bracing rethink of Victorian history that for the first time shows to what extent females, in life and in fiction, were going about police work undetected.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

‘At times, Orbital feels almost like a long poem.’

@sam3reynolds on Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, the winner of this year’s @TheBookerPrizes

Sam Reynolds - Islands in the Sky

Sam Reynolds: Islands in the Sky - Orbital by Samantha Harvey

literaryreview.co.uk

Nick Harkaway, John le Carré's son, has gone back to the 1960s with a new novel featuring his father's anti-hero, George Smiley.

But is this the missing link in le Carré’s oeuvre, asks @ddguttenplan, or is there something awry?

D D Guttenplan - Smiley Redux

D D Guttenplan: Smiley Redux - Karla’s Choice by Nick Harkaway

literaryreview.co.uk

In the nine centuries since his death, El Cid has been presented as a prototypical crusader, a paragon of religious toleration and the progenitor of a united Spain.

David Abulafia goes in search of the real El Cid.

David Abulafia - Legends of the Phantom Rider

David Abulafia: Legends of the Phantom Rider - El Cid: The Life and Afterlife of a Medieval Mercenary by Nora Berend

literaryreview.co.uk