Paul Lay

A Decanter of Deacons

A Field Guide to the English Clergy: A Compendium of Diverse Eccentrics, Pirates, Prelates and Adventurers; All Anglican, Some Even Practising

By Fergus Butler-Gallie

Oneworld 175pp £12.99

That the Church of England is theologically flexible will come as no surprise to observers of the institution described by the High Tory poet C H Sisson as ‘the one Sun seen … through the mists of this island’. But even by the standards of the C of E, the career of Marco de Dominis was one of a Christian contortionist. Born in a part of Croatia that, in the 16th and 17th centuries, belonged to Venice, he became a propagandist for the Venetian cause, railing against the papal interdict inflicted on the republic for its insistence on nominating bishops in its Balkan territories. When Venice finally reached an accord with Rome in 1615, de Dominis fled to England, where he converted to Anglicanism and plotted with James I to bring Venice into the orbit of the C of E, an ambitious scheme if ever there was one. The Croatian was appointed dean of Windsor, a fabulously wealthy post in which he proved unpopular. Lured by the even more lucrative offer of a Sicilian bishopric, de Dominis converted back to Catholicism, a big mistake given that the Inquisition retained memories of the many duplicities of an individual described by an Anglican colleague as ‘odious both to God and to man’.

De Dominis is one of the more serious – and seriously unpleasant – figures to grace Fergus Butler-Gallie’s entertainingly erudite series of sketches of the Church of England’s capacious wing of ‘Eccentrics’, ‘Nutty Professors’, ‘Bon Viveurs’, ‘Prodigal Sons’ and ‘Rogues’. Some of the names will be familiar: William Spooner, the word-transposing warden of New College, Oxford, who gave us the spoonerism; Michael Ramsey, the ‘autistic’ Congregationalist convert who, despite being ‘totally unsuitable’ for the job, was made Archbishop of Canterbury at the behest of Harold Macmillan; Brian Brindley, the outrageously camp high churchman who died during his seventieth birthday dinner at the Athenaeum Club and became the subject of one of the great Daily Telegraph obituaries.

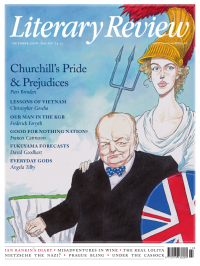

The cover, the title and the excellent illustrations suggest a book of Wodehousian levity, and there is much of that. But it is also, wittingly or unwittingly, a surprisingly profound work. Yes, there is no shortage of the nefarious, the louche and the useless in these pages, such as the

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Under its longest-serving editor, Graydon Carter, Vanity Fair was that rare thing – a New York society magazine that published serious journalism.

@PeterPeteryork looks at what Carter got right.

Peter York - Deluxe Editions

Peter York: Deluxe Editions - When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines by Graydon Carter

literaryreview.co.uk

Henry James returned to America in 1904 with three objectives: to see his brother William, to deliver a series of lectures on Balzac, and to gather material for a pair of books about modern America.

Peter Rose follows James out west.

Peter Rose - The Restless Analyst

Peter Rose: The Restless Analyst - Henry James Comes Home: Rediscovering America in the Gilded Age by Peter Brooks...

literaryreview.co.uk

Vladimir Putin served his apprenticeship in the KGB toward the end of the Cold War, a period during which Western societies were infiltrated by so-called 'illegals'.

Piers Brendon examines how the culture of Soviet spycraft shaped his thinking.

Piers Brendon - Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll

Piers Brendon: Tinker, Tailor, Sleeper, Troll - The Illegals: Russia’s Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West by Shaun Walker

literaryreview.co.uk