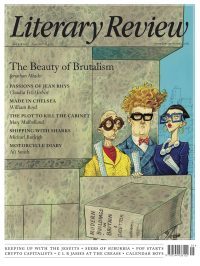

Jonathan Meades

Castles of Concrete

Modern Buildings in Britain: A Gazetteer

By Owen Hatherley

Particular Books 608pp £60

Owen Hatherley blithely claims that this massive tour de force is ‘a guide to the place … you’re visiting, or a place you want to visit’. Pull the other one, squire. The notion of Owen Hatherley, Tripadvisor, is sheerly preposterous, though it may appeal to a tremulous publisher figuring out how to market this behemoth. He is really a polemicist, ready to take issue with anyone, including himself. His insistent invitations to look are heavy with allusions, catholic comparisons and quiet asides. The result of his tireless labour is an oblique, partial, lopsided survey of Britain throughout the long modernist century; and no matter what a platoon of celluloid collars and triple-breasted waistcoats may have wished for, modernism did triumph, in many guises. Its variety goes unnoticed by its antagonists, who have no ability to discern the kinship of much modernist architecture to its medieval and Victorian precursors. What they do have, in abundance, is torpid prejudice. This approximate gazetteer will not convince the obstinate to change their minds. But that really is not its point. It is a gorgeous treat for the already converted and, maybe, for those impaled on the spikes of equivocation. Hatherley’s only historical blunder is to describe Art Nouveau as ‘a mechanized sub-species of the Arts and Crafts’. The latter was pretty much exclusively English; the former was its flashy contemporary in places such as Belgium, Catalonia and Nancy. They hardly infected each other.

Hatherley goes on a taxonomical spree. He has identified fifteen types of modernism. Most make sense, though examples of certain types are rare and hardly merit being placed in a separate category, while others resist all but the most sweeping of labels. Buildings are, evidently, human constructs. They are not accommodating to scientific measurement and analysis, even though, in the wake of Rickman, Pevsner and other pigeonholers, a school of historians wishes they were. Hatherley is, as ever, zealous in his avoidance of the debased, jargon-dense prose that is obligatory in architectural schools and journals.

He makes it clear that he is writing for a constituency that architects patronisingly refer to as the ‘lay public’. That rather hints at how the trade regards itself. Each building in this book, which is arranged by region, is placed into one of the fifteen categories Hatherley has devised, so that every entry is labelled ‘Classical Modernism’, ‘Modernist Eclectic’, ‘Moderne’ and so on. Perhaps the presumably untutored lay public needs to have its hand held. Maybe it needs the guidance furnished by such terms as ‘People’s Detailing’, ‘Pseudomodernism’, ‘Constructivism’ and ‘Ecomodernism’, of the last of which there’s not much here. Should that surprise us, given that every architect in the world routinely describes their work as ‘sustainable’? Not really: the term is just a collective lie.

Whether this exercise in classification is anything more than a sometimes confusing encumbrance is questionable. It doesn’t answer the question ‘is it any good?’ There are so many buildings tagged ‘Brutalist’ that one soon loses track of what the epithet means, if anything. To me it means sublimity, concrete, the inspiration of eroded hoodoos and incongruous erratics, sculptural complexity, multiple accretions, Vanbrugh’s ‘castle air’. It is more a mood (of high optimism and humankind’s celebration of itself) than a style. Hatherley’s idea of brutalism is far more inclusive.

In any era, most of what is built is mediocre going on dull. Richard Rogers’s Lloyd’s building, one of the more celebrated and thrilling works in this book, is not marked as ‘Brutalist’ but as ‘High-Tech, Constructivist’. Where do you draw the line? Imagine it cast in concrete rather than in steel: its debt to Rogers’s teacher at Yale, the doggedly counterintuitive brutalist Paul Rudolph, becomes immediately apparent.

The whole world knows Rogers. His buildings were advertisements for himself. It is unlikely that even the inhabitants of Basingstoke know that their town, lying in the ambitiously named ‘southern sunbelt’, was once, as Hatherley explains, called the ‘Dallas of Hampshire’ or that the mid-1970s Gateway House was known as the ‘hanging gardens of Basingstoke’.

It is the thousand and more such sketches of the local and the overlooked that lend this book its density and drive, and emphasise Britain’s mostly low-key riches – if only you can be bothered to buy an anorak and seek. It’s a delightful pursuit and it’s free. Hatherley does not get bored. He is a flâneur with a cause. He incites his readers to engage, as he does, with what is around them, no matter how banal it may appear at first glance, and to take nothing for granted.

These buildings and hundreds of others, the majority in the regions, constitute what the architect Peter Aldington (not present) called a ‘better standard of ordinariness’. They include Andy MacMillan and Isi Metzstein’s St Bride’s Church, East Kilbride; Alexander Buchanan Campbell’s baths in the same (no longer new) town; Roger Booth’s astonishing works for Lancashire County Council (there is no police station in the country as terrifying as Blackpool’s); F K Hicklin’s lowering County Hall in Truro, a minatory beast waiting to pounce; N F Cachemaille-Day’s and George Pace’s churches at, respectively, Eltham and Keele University; everything by Alan Short, whose buildings’ silhouettes recall the works of Yves Tanguy; the cafe between Dundee and Perth with a roof graced by a life-sized fibreglass Friesian cow, the markings of which form a map of the world; Cables Wynd House near Leith docks; Laurie Abbott’s houses at Frimley; and Peter Barber’s inspired social housing, which both borrows from white cubistic modernism and revives its social programme.

Their makers did not belong to the perpetually jet-lagged cadre of starchitects. They were low-profile craftsmen and artists rather than corporate businessmen. Which is not to say they were unappreciative of recognition. When MacMillan and Metzstein were awarded a gong by RIBA, the latter remarked, ‘it would have been even better to receive this while we were still alive.’ They were among the victims of halfwitted local authorities who were happy to maim or demolish buildings which might easily have been given a new use (Nadine Dorries appears to have taken her cue from them). The most slighted of all were Owen Luder and Rodney Gordon, whose magnificent essays in sod-you-ism have long since been turned to rubble and replaced by shit. They have some claim to have been the greatest of British brutalists. They are largely absent here. So too, bizarrely, are such delights as Richard Gilbert Scott’s wacky Our Lady Help of Christians at Tile Cross in the eastern suburbs of Birmingham, a nightclub that has escaped from Las Vegas and signed up to the Catholic faith, and H T Cadbury-Brown’s Royal College of Art, as well as the beautiful house the architect built for himself at Aldeburgh.

This last absence is explained by Hatherley’s decision to omit houses which are not open to the public and cannot be seen from the street. Thus an entire strain of mostly low-budget invention is missing. The gap it leaves is not without consequence. It lends the book a strong bias towards public patronage, to welfarism, to the dubiously named ‘postwar consensus’, which only seemed a consensus after Thatcher tore it apart. There is, then, another chapter to be written, though Hatherley might reckon it to be politically improper. This scrupulous writer’s taste is for actual socialism, rather than the prosecco socialism de rigueur among private clients of modernist architects.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

It wasn’t until 1825 that Pepys’s diary became available for the first time. How it was eventually decrypted and published is a story of subterfuge and duplicity.

Kate Loveman tells the tale.

Kate Loveman - Publishing Pepys

Kate Loveman: Publishing Pepys

literaryreview.co.uk

Arthur Christopher Benson was a pillar of the Edwardian establishment. He was supremely well connected. As his newly published diaries reveal, he was also riotously indiscreet.

Piers Brendon compares Benson’s journals to others from the 20th century.

Piers Brendon - Land of Dopes & Tories

Piers Brendon: Land of Dopes & Tories - The Benson Diaries: Selections from the Diary of Arthur Christopher Benson by Eamon Duffy & Ronald Hyam (edd)

literaryreview.co.uk

Of the siblings Gwen and Augustus John, it is Augustus who has commanded most attention from collectors and connoisseurs.

Was he really the finer artist, asks Tanya Harrod, or is it time Gwen emerged from her brother’s shadow?

Tanya Harrod - Cut from the Same Canvas

Tanya Harrod: Cut from the Same Canvas - Artists, Siblings, Visionaries: The Lives and Loves of Gwen and Augustus John by Judith Mackrell

literaryreview.co.uk