Seamus Perry

Crying with Laughter

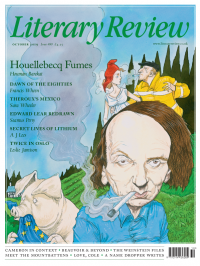

Inventing Edward Lear

By Sara Lodge

Harvard University Press 436pp £23.95

Long ago, when the Victorians were regarded as moralistic old windbags, Edward Lear, who could hardly have been less ‘serious’, was bound to seem a peripheral figure, and found himself duly exiled to the nursery. But once we realised that the Victorians had quite as many troubles and neuroses as we do – indeed, that it was the Victorians who were largely responsible for inventing the troubles and neuroses which we think of as our modern lot – Lear began to seem more and more exemplary of his age, rather than the nonsensical alternative to it. An unhappy childhood (‘brought up by women – and badly besides’), the dark shadow cast by his epilepsy (his ‘daemon’), lifelong loneliness and depression (‘morbidiousness’): Lear offers the perennial fascination of a case and has been very well served on the whole by his biographers. Angus Davidson’s Edward Lear: Landscape Painter and Nonsense Poet (1938) was the trailblazer. The acknowledged masterpiece is Vivien Noakes’s Edward Lear: The Life of a Wanderer (1968), though I think Jenny Uglow’s recent Mr Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense (2017) is quite its equal, a humane and profoundly acquainted portrait of Lear in all his sadness and queer resilience.

W H Auden, who was well versed in psychoanalytic theory, wrote a very fine sonnet after reading Davidson’s book, in which he described how Lear’s self-hatred and deeply repressed emotional life somehow translated into the shared compensations of his poetry. ‘Children swarmed to him like settlers,’ wrote Auden, most beautifully. ‘He became a land.’ Learland appeals to children because it is all about how deeply peculiar grown-ups are, but it is also reassuring in that it treats their weird goings-on with largely untroubled acceptance:

There was an Old Man of Whitehaven,

Who danced a quadrille with a Raven;

But they said, ‘It’s absurd to encourage this bird!’

So they smashed that Old Man of Whitehaven.

The mixture of violence and levity is the magic recipe, one that Lear used again and again to remarkable effect. This is a brutal poem and yet it is easy and delightful at the same time. One of the best things ever said about Lear was the scholar Thomas Byrom’s observation that while the poems are full of glum or gruesome episodes stoically endured, their accompanying illustrations usually convey some mysterious sense of happiness. That’s true of this limerick, where the picture that goes with it shows the Old Man and the Raven dancing like Laurel and Hardy in Way Out West. A Victorian critic detected in these highly idiosyncratic poems a ‘totally new sensation of humour, welt-schmerz, mystery, and farce combined’. Or, as Sara Lodge puts it in her deeply knowledgeable and sharply written new book, in Lear ‘pathos and absurdity typically form a feedback loop’, so that the most heartbreaking feeling can find a way of being articulated through the making of a joke.

He weeps by the side of the ocean,

He weeps on the top of the hill;

He purchases pancakes and lotion,

And chocolate shrimps from the mill.

That verse begins as a spoof on Romantic lachrymosity but modulates, via the irrelevance of a report on consumer habits, to complete absurdity. It’s a joke, but it’s also a portrait of someone who can’t stop crying.

Lodge has not written a biography of Lear, though her book is full of biographical information. It is more a study in contexts, returning Lear to the local sources from which his apparently autonomous imaginative world originally gathered its strength. One of these, perhaps the most striking, is the Victorian culture of singing at home, at which Lear was a widely welcomed adept. (Lodge and some friends have recorded several contemporary songs and the book includes directions to the webpage where you can listen to them.) The same tunes might be put to poignant or hilarious purposes: gathered around the piano for an evening’s home entertainment, the performance would veer between the tear-jerking and the side-splitting in a way that seems characteristic of the age. It is the very stuff of Dickens – you think of Wilde’s astute remark about the death of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop being a scene that only someone with a heart of stone could read without laughing. Lear seems to have taken the epochal genius for emotional ambiguity to its furthest reach: a contemporary was struck that the poet could perform a setting of Tennyson’s ‘Tears, Idle Tears’ and sob like a child, but then, shortly afterwards, embark on an ingenious spoof on the same poetry.

Lear was not at all ‘Victorian’, however, in that he seemed blithely untroubled by the intellectual turbulence of the age. A distinguished zoological draughtsman, he kept himself informed about contemporary scientific developments and revered Darwin. He read Matthew Arnold’s Literature and Dogma, a bestselling work of liberal theology which deftly abandoned most of the doctrines that had previously defined Christianity, and was enthusiastic about W H Lecky, whose remarkable History of the Rise and Influence of Rationalism in Europe (1865) he thought ‘delightful’.

Lear’s own background, Lodge reminds us, was Dissenting, and he often expressed his disdain for the established Church, the narrowness of its moral teachings and the predictable tedium of its sermons. As she notes, his poems commemorate oddballs and those who choose to opt out in one way or another, like the imprudent Old Man of Whitehaven, though attributing this admirable defence of individualism to the world of Victorian Dissent may be a bit of a stretch: the culture of the chapels had many virtues to recommend it, no doubt, but that delight in ‘the variety of modes of being’ which Lodge finds at the heart of Lear’s imagination does not stand out among them.

Lodge is keen to make Lear come across as a sociable artist, one whose work ‘invokes sociability as its subject, its metier and its raison d’être’, and she is encouraged here perhaps by the example of those communal musical performances, which clearly had such an influence upon him. But, having read her rich and sympathetic book, I came to think almost exactly the opposite. Lodge describes her subject as ‘a character who signals that he needs or deserves to be cared for’, which sounds slightly repellent (and is something that most children would surely find a bit of a drag). I would have said the impression Lear leaves you with is one of intense reserve, a privacy guarded by a high thick wall of merriment and punning. Lewis Carroll, in his donnish way, is deeply collusive, positively inviting you to be clever enough to join him in the joke, but the best of Lear has a kind of impenetrability or unreadability that sets you firmly at arm’s length from whatever sadness or trouble might originally have been stirring, as though it’s none of your business whether to take these feelings seriously or not:

There was an Old Man of Cape Horn,

Who wished he had never been born;

So he sat on a chair, till he died of despair,

That dolorous Man of Cape Horn.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk