Seamus Perry

Into That Good Night

The Lighted Window: Evening Walks Remembered

By Peter Davidson

Bodleian Library Publishing 216pp £25

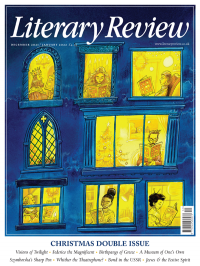

Peter Davidson has long displayed a kind of genius for writing about subjects that are both deeply fascinating and tantalisingly elusive, things that stick in your mind but that, in some ways, you feel to be hardly there at all. He wrote a wonderful book about the idea of things being thought of as northerly, for instance, and another about the ways in which painters and writers have been drawn to imagine the exemplarily indefinable moment of twilight. His new book, a very handsome and generously illustrated production, is about a topic which is, if anything, even harder to pin down: the night-time experience of gazing at an illuminated window. What he has produced is less a monograph than a study – an academic study to the extent that it is, like all of Davidson’s writings, full of strikingly diverse erudition, but also a study like something from a Constable sketchbook, all the more atmospheric for the sense it conveys of being improvisatory and unfinished.

Davidson is evidently a great wanderer and his book, largely an account of his nocturnal wanderings and the thoughts inspired by them, is itself an engagingly wandering affair. It is a work of great charm, moving from text to text and painting to painting in a disarmingly associative way: the connective tissue of the work is a network of phrases such as ‘My mind circles back…’, ‘I think of other lights which shine in more than one dimension…’, ‘I am reminded of an odd fragment of narrative…’ and ‘My thoughts moved to a far comparison…’. We begin and end accompanying the author through the crepuscular autumnal fog beside the Thames in Oxford, and in between we follow him through the sighing willows of Ghent, the frozen mid-afternoon darkness of Stockholm, the scruffy urban romance of central London, the smart neoclassical streets of Edinburgh’s New Town, the autumnal fields of Norfolk and the snows of Princeton. And as we make our way, Davidson tells us what emerges from his extraordinarily well-stocked mind. There are passages from Matthew Arnold and W H Auden, Virginia Woolf and Arthur Conan Doyle, Chesterton and Hopkins, Baudelaire and Proust and Apollinaire and many more, all brought into streamy consciousness alongside painters of lit-up windows, from Samuel Palmer to Edward Hopper, Thomas Gainsborough to Joan Eardley, Eric Ravilious to George Clausen, and several exquisite Japanese creators of nocturnal scenes (Kawase Hasui, Uehara Konen, Takahashi Shōtei), which were, to me, among the most lovely of the numerous discoveries here. There isn’t a Faber Book of Windows at Night, but Davidson is certainly the man for the job and The Lighted Window is a sort of memoir of the thought processes that would have produced one.

Davidson is very good at evoking the strange suspendedness of both his own experiences and those his writers and painters depict. The image of Arnold’s scholar gypsy gazing down from Cumnor Hill to the flickering lights in Christ Church hall sets the tone for a book that is preoccupied with what it feels like to have an imperfect glimpse into the world of someone else, a world in which you know, as the poor old scholar knew freezing on his hill, you will never participate. At one point, Davidson recounts a story, or rather a non-story, of the time he caught sight from the pavement of the interior of an apartment in Edinburgh: ‘I could see that there were six candles lit on the mantelpiece of what seemed otherwise an empty room – no pictures and no curtains, shutters open, the panes of glass in the window very clean.’ You could imagine a short story beginning with such a vignette, but Davidson’s episode has a wholly characteristic end-stopped quality and absolutely nothing happens, just as nothing ever happens in a Palmer painting. But despite being utterly inconsequential, the sighting was, he says, ‘oddly memorable’, and it is such odd memorability that is his theme throughout: the way that rare moments create an unexpected sense of acquaintance with a stranger while, at the same time, confirming your unbridgeable separateness. That makes the book sound rather melancholy, perhaps, and although there are many graceful tributes to friends and walking companions, Davidson is especially good on the solitariness implicit in his subject – as in the paintings of Hopper, ‘sad in themselves but intensified by the sadness implied in the position of the spectator’. Even the delightful lithographs of London shops by Ravilious, which are indeed, as Davidson says, ‘mostly cheerful’, possess as well ‘an element of quiet strangeness’.

It is naturally difficult to write about such precious experiences without coming across as precious in the bad sense of the word, but Davidson steps around the trap of fine writing very nicely, mostly thanks to the palpable and infectious delight he takes in just knowing so much interesting stuff. But of course it is the nature of such a book – indeed, it is practically one of its duties – to provoke the reader to think of other works that might have fallen within its scope. I kept thinking of Wordsworth’s ‘Michael’, in which the cottage of the shepherd and his wife is known throughout Grasmere vale for its illuminated window: ‘This light was famous in its neighbourhood’, Wordsworth tells us, ‘And was a public symbol of the life/That thrifty Pair had lived’. The villagers call his home ‘The Evening Star’, intimating a kind of perpetuity that turns out to be sadly inapposite to Michael’s tragic tale. And then there is Larkin’s dreadful depiction of old age:

Perhaps being old is having lighted rooms

Inside your head, and people in them, acting.

People you know, yet can’t quite name…

Larkin’s particular terror is a deeply personal affair, but the eerie pity evoked by overlooked illuminated domestic spaces is the common possession of artists, as this book handsomely and variously demonstrates.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk