Seamus Perry

What Lies Beneath

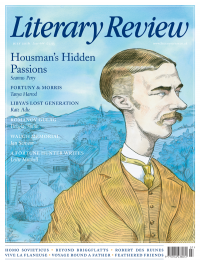

Housman Country: Into the Heart of England

By Peter Parker

Little, Brown 544pp £25

A E Housman remains the best advertisement in English literature for the enabling power of repression. He was, as his brother Laurence said, ‘provokingly reserved’, though from beneath the lid he kept so firmly screwed down emerged rare fleeting glimpses of the tempestuous stuff that was always going on inside. Housman was, as Auden put it in his fine, admiring poem, the ‘Latin Scholar of his generation’, but his approach to classical literature was ostentatiously arid, as though deliberately to keep anything like feeling at arm’s length. He wrote about minute matters of textual scholarship with brilliant precision and utter authority, regarding the efforts of less adequate scholars with devastating contempt. He did not suffer fools, let alone gladly. You could not imagine higher ground to occupy. Take, for example, his account of the abject failure of generations of earlier editors to figure out the relationship between the manuscripts of Juvenal: ‘Three minutes’ thought would suffice to find this out; but thought is irksome and three minutes is a long time.’ The whole performance was one of testy brilliance, the artful cultivation of the persona of an ‘odious editor’ with a ‘deplorable reputation’, showing, Swift-like, his worst face to the world. When the mask slipped the effect was naturally astonishing. One memoirist recalled the last talk in a long, dry-sounding lecture series in Cambridge about Horace, at the end of which, to everyone’s surprise, Housman said, ‘I should like to spend the last few minutes considering this ode simply as poetry.’ He read it both in Latin and in his own translation, and then commented, ‘almost like a man betraying a secret, “I regard [that] as the most beautiful poem in ancient literature,” and walked quickly out of the room’. The effect was terrific: one student said to another, ‘I was afraid the old fellow was going to cry.’

Housman himself credited poetry with just such disruptive power – the capacity momentarily to free up those levels of the personality that were normally kept tightly under wraps. For instance, Milton’s words ‘Nymphs and shepherds, dance no more’ were on their own capable of bringing tears to the eyes, he told the audience at his remarkable lecture ‘The Name and Nature of Poetry’, going on to wonder out loud: ‘What in the world is there to cry about?’ The answer lay somehow in the magic of the words, which, just because they were real poetry, ‘find their way to something in man which is obscure and latent, something older than the present organization of his nature’.

That puts the point at its most general, as though it were some primitive aspect of humanity at large that was being touched; but in truth Housman had a very specific thing in the world to cry about, or rather not to cry about. Moses Jackson was a fellow undergraduate at Oxford: he was a gifted physicist, straightforward, lithe, athletic and gorgeous, ‘lively, but not at all witty’ the eminent Shakespearean A W Pollard later recollected, and above all, as a contemporary remarked, ‘a perfect Philistine’. He was, in short, Housman’s precise antitype: blissfully unliterary and, as it would shortly transpire, unmitigatedly heterosexual. Housman seems to have declared his feelings once they had left Oxford and were both working in the Patent Office. Jackson’s response is not known, but it was clearly a refusal. Housman uncharacteristically went missing for a week and his associates seem to have feared the worst, but things were patched up and they remained friends: perhaps, Peter Parker suggests in his likeable new study, years at a good public school and then Oxford had inured Jackson to professions of adoration. Jackson married, had children, worked in India then in Canada, and led an admirable but wholly normal sort of life. Throughout it all, Housman loved him with a Wagnerian intensity that was simply undeviating and all the more consuming for going unsaid. The letters to him are exercises in blokeish tenderness. ‘Why not rise superior to the natural disagreeableness of your character and behave nicely for once in a way to a fellow who thinks more of you than anything in the world?’ Housman wrote, trying to get Jackson to accept a loan. If you think you have loved more than once, he told an acquaintance, you’ve never really loved at all. When news of Jackson’s death arrived in 1923, Housman wrote, extraordinarily, to Pollard: ‘Now I can die myself: I could not have borne to leave him behind me in a world where anything might happen to him.’ A photograph continued to hang above his study fireplace. His brother once asked him the name of the subject: ‘In a strangely moved voice he answered, “that was my friend Jackson, the man who had more influence on my life than anyone else”.’

Part of that influence, as Housman said, was making a poet of him, and perhaps he made of Jackson just what he needed to become the poet that he was. The poems of his masterpiece, A Shropshire Lad, came in a great rush, many written in the first half of 1895, coincidentally while Oscar Wilde was on trial. The repression of Housman’s personality found its way into a unique lyric voice at once expressive and utterly secretive. It proved instantly popular and has remained so ever since:

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

What, indeed: the abiding reticence about just what is the matter makes these clipped, passionate poems remarkably open to being received in very different ways by their readers. That feeling in Housman’s poems has always evaded critical summary: Parker has some good stabs at capturing the effect – he describes much of Housman’s writing as ‘a decorous pavane of concealment and revelation’ and characterises the tone of one particular poem as ‘slippery’ – but I am not sure anyone has bettered John Bayley’s account, in Housman’s Poems (1992), of the ‘blend of ceremonious formality with secrecy, a hidden intimacy’. The cruel wit of the scholarship is modulated in the poems into a much more complicated sort of black humour, which admits the profoundest sort of passion while professing to pass it off as nothing to get worked up about. If you were to paraphrase them or put them into French, they would seem consistently bleak, and they are of course deeply unhappy; but everyone who loves them appreciates their curious buoyancy, which proves a kind of resilience. Housman wasn’t just joking when, agreeing to have his poems published in Braille, he remarked: ‘The blind want cheering up’.

Parker’s book is as much around A Shropshire Lad as about it: he sees its mixture of eroticism and reticence as essentially English and treats the book as ‘a gazetteer of the English heart’, allowing him to range beyond Housman’s life more broadly into cultural history and to locate the poet within changing attitudes towards English history, landscape and the early 20th-century resurgence of interest in English music. It could not be said that Housman contributed to any of these important movements with much purpose. Weary city-dwellers who, inspired by H V Morton’s best-selling In Search of England (1927) or the Shell Guides, headed off in the Austin for a bracing weekend in Shropshire would have discovered the poems a very imperfect handbook to the topography of the place: ‘The vane on Hughley steeple/Veers bright, a far-known sign’ in A Shropshire Lad, but it doesn’t in Shropshire since it is buried deep in a valley. Parker is interesting on the numerous musical settings of the poems, many of which are indeed lovely; but Housman proved a comically unwilling participant in the rebirth of English song. The composer Herbert Howells was dismayed to hear Housman at high table in Trinity lay into Vaughan Williams and Butterworth for what they ‘had done for all his verse’. (Howells kept mum about his own efforts and later destroyed them.) But if nothing could have been less to Housman’s taste than contributing to a cultural resurgence, Parker persuades you that his influence indeed spread wide. There are some particularly good pages on the remarkable popularity his work enjoyed among English soldiers and he traces assiduously Housman’s influence down to the present day, from references in The Archers and Inspector Morse to Quieter than Spiders (‘a synthpop band based in Shanghai’). It is a diverting and various book, and I mean to praise when I say that, for all the resourceful deployment of such eclectic contexts, Housman himself remains as elusive as ever. The English come across as agreeably odd. My favourite is Anthony Chenevix-Trench, who diverted himself by translating Housman into Latin while breaking stones as a prisoner of war on the Burma railway. ‘Not often can Latin verses have been composed in such untoward circumstances’, remarked his old school magazine, which must deserve a prize. Housman would have enjoyed the understatement, as Parker says.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Margaret Atwood has become a cultural weathervane, blamed for predicting dystopia and celebrated for resisting it. Yet her ‘memoir of sorts’ reveals a more complicated, playful figure.

@sophieolive introduces us to a young Peggy.

Sophie Oliver - Ms Fixit’s Characteristics

Sophie Oliver: Ms Fixit’s Characteristics - Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

literaryreview.co.uk

For a writer so ubiquitous, George Orwell remains curiously elusive. His voice is lost, his image scarce; all that survives is the prose, and the interpretations built upon it.

@Dorianlynskey wonders what is to be done.

Dorian Lynskey - Doublethink & Doubt

Dorian Lynskey: Doublethink & Doubt - Orwell: 2+2=5 by Raoul Peck (dir); George Orwell: Life and Legacy by Robert Colls

literaryreview.co.uk

The court of Henry VIII is easy to envision thanks to Hans Holbein the Younger’s portraits: the bearded king, Anne of Cleves in red and gold, Thomas Cromwell demure in black.

Peter Marshall paints a picture of the artist himself.

Peter Marshall - Varnish & Virtue

Peter Marshall: Varnish & Virtue - Holbein: Renaissance Master by Elizabeth Goldring

literaryreview.co.uk