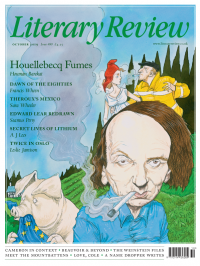

Houman Barekat

Fagged Out & Furious

Serotonin

By Michel Houellebecq

William Heinemann 320pp £20

There was a time when chain-smoking connoted a rugged, implicitly countercultural glamour: I once knew a musician who insisted on posing fag-in-mouth in his promotional photos, despite being a fastidious non-smoker. The habit is rather less cool these days; most of us are okay with that, but there is a certain species of chuntering crank for whom its marginalisation rankles with all the bitterness of a major historical grievance, symbolising nothing less than the crushing of the human spirit by the joyless technocracy of an overweening state. Florent-Claude Labrouste, the forty-something narrator-protagonist of Michel Houellebecq’s seventh novel, is one such bore. He sabotages smoke detectors in hotel rooms and whines about speed restrictions; he is the proud owner of a diesel 4×4, declaring that ‘I mightn’t have done much good in my life, but at least I contributed to the destruction of the planet.’ He is, of course, deeply unhappy, and Serotonin is the story of his breakdown.

Upon discovering that his much younger partner, Yuzu, has been engaging in illicit group sex with a number of other men – and some dogs – Florent-Claude walks out on her, quits his job as a government agronomist and scarpers to the Normandy countryside. Prior to leaving Paris he consults a psychiatrist – he doesn’t trust them as a rule, but this one smokes Camels on the job and is therefore sound – who gives him a prescription for a potent new antidepressant that will level him out, at the expense of his libido. The story is told in a register of plaintive resignation, laced with Houellebecq’s customary black humour. Florent-Claude has been ‘an inconsistent wimp’ all his life, his ‘simple nature’ ill-suited to the complexities of modern living. He is haunted by the memories of two failed relationships, which he dissects at length in tones of wistful self-reproach. His is ‘a peaceful, stable sadness, not susceptible to increase or decrease; a sadness, in short, that to all intents and purposes appeared definitive.’ Having blown his chances of fulfilling ‘the promise of happiness’ – this phrase, an allusion to Stendhal’s definition of beauty, crops up more than once – he must content himself with finding comfort in small, banal pleasures: the eight different varieties of hummus on sale at the Carrefour supermarket are a particular source of existential solace.

In the countryside Florent-Claude reconnects with an old university friend called Aymeric, a farmer whose wife has just left him for a concert pianist. The two men reminisce about rock concerts and discuss the tribulations of an agriculture industry squeezed by global competition and EU rules. Aymeric participates in a blockade by dairy farmers opposed to the abolition of milk quotas, which leads to an armed confrontation with riot police. Here Houellebecq reprises the core themes of his previous novel, Submission (2015): a nation meekly surrendering its birthright; the twinning of personal and political emasculation; and the suggestion that if there is any hope, it lies in the provinces. The author’s sympathies are with the insurgents, but a large dollop of farce ensures we are never quite in the realm of the earnest protest novel: the farmers arm themselves with rocket launchers; Aymeric ends up on the front pages of the newspapers, pictured with a joint hanging out of his mouth.

Serotonin contains a fair smattering of casual racism, mainly at the expense of the Chinese, Vietnamese and Japanese – cheap, well-worn gags about anatomical traits and peculiarities of diction. This will jar with some readers, as will the offhand crassness with which Houellebecq’s narrator reflects on his sexual conquests. He remarks of Yuzu that ‘the best thing about her’ was ‘her arsehole, the permanent availability of her arsehole, apparently tight but in fact so manageable’. The author’s reputation for chauvinism precedes him, but in the case of this particular novel at least, he can avail himself of the defence successfully invoked by Gustave Flaubert when Madame Bovary was up before the courts on obscenity charges all those years ago: Flaubert averred that he could not have been glamorising adultery because his heroine comes to a sticky end. Likewise Serotonin reads like a cautionary tale about dissipated manhood, the kind of thing any self-respecting Guardian reader can get behind. ‘I will end my life unhappy, cantankerous and alone,’ Florent-Claude soliloquises, ‘and I will have deserved it.’ Has the arch-provocateur gone soft in old age? Houellebecq remarried last year, and there is a sense of ‘there but for the grace of God go I’ about this novel, which pays grudging homage to stable monogamy as the only viable antidote to the loneliness of urban modernity.

That an author so notoriously sex-obsessed should concern himself with something as wholesome as ‘happiness’ looks, at first sight, like something of a contradiction. But Houellebecq was never really a hedonist. While often gratuitously graphic, his sex scenes are notably listless: related in blandly functional prose, they are conspicuously devoid of eroticism or joy. What some have interpreted as licentiousness could in fact be seen as the inverted prudery of the repressed social conservative. In Houellebecq’s fiction the libido, whether waxing or waning, is a problem to be overcome.

In an essay published in Harper’s earlier this year, Houellebecq praised Donald Trump’s protectionist economic policies, describing his administration as a ‘necessary ordeal’, a corrective to the free market fundamentalism that has dominated Western politics for so long. His disaffected protagonists embody the impulse, common to Left and Right alike, to halt the juggernaut of unfettered globalisation. In his novels, an individual’s existential ennui is often pointedly juxtaposed with the theme of socio-economic subjugation: foreign money plays a central role in the fanciful political upheavals imagined in Submission; in his Prix Goncourt-winning The Map and the Territory (2010), the French countryside becomes a plaything for Chinese and Russian oligarchs; the bête noire in Serotonin is the EU. Houellebecq’s engagement with political economy compares favourably to its treatment in our recent glut of Brexit novels. Many of these are too unabashedly polemical, reading like think-pieces on demagoguery and xenophobia, padded out with bits of story. Nor do they concern themselves sufficiently with the world in the round: the 2016 referendum and its aftermath are viewed in isolation, without reference to the broader economic context.

Although Houellebecq may be, in certain respects, a man for our times, some of the claims made on his behalf are overblown. He is not the bard of the Gilets Jaunes movement; nor is he a thorn in the side of the establishment. His rakish aesthetic notwithstanding, he is countercultural only in a heavily circumscribed sense. He recently had France’s highest order of merit, the Légion d’honneur, bestowed upon him by a president whose politics are antithetical to his own.

Whatever one thinks of his views, Houellebecq must be commended for his acute rendering of the intrinsically melancholic nature of chauvinism. Houellebecq’s portrait of the reactionary id is all the more convincing for being riddled with contradictions, echoing the intellectual incoherence that has characterised Europe’s nativist surge. There is a telling moment when Florent-Claude, having railed against the dogmas of free trade and globalisation, advises Aymeric to go wife-shopping in the developing world: ‘Take a Moldovan girl, or a Cameroonian or a Malagasy girl, a Laotian even … They’ll be up and about at five in the morning to do the milking … then they’ll wake you up with a blow-job, and breakfast will be ready as well.’ France for the French, then; but we can still be cosmopolitans when it suits us.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Russia’s recent efforts to destabilise the Baltic states have increased enthusiasm for the EU in these places. With Euroscepticism growing in countries like France and Germany, @owenmatth wonders whether Europe’s salvation will come from its periphery.

Owen Matthews - Sea of Troubles

Owen Matthews: Sea of Troubles - Baltic: The Future of Europe by Oliver Moody

literaryreview.co.uk

Many laptop workers will find Vincenzo Latronico’s PERFECTION sends shivers of uncomfortable recognition down their spine. I wrote about why for @Lit_Review

https://literaryreview.co.uk/hashtag-living

An insightful review by @DanielB89913888 of In Covid’s Wake (Macedo & Lee, @PrincetonUPress).

Paraphrasing: left-leaning authors critique the Covid response using right-wing arguments. A fascinating read.

via @Lit_Review