Seamus Perry

Before the Beard

The Boundless Deep: Young Tennyson, Science, and the Crisis of Belief

By Richard Holmes

William Collins 430pp £25

Edward FitzGerald long remembered the heavenly spectacle of his younger contemporary Alfred Tennyson at Cambridge. ‘At that time he looked something like the Hyperion shorn of his Beams in Keats’s Poem’, FitzGerald wrote fifty years later, ‘with a Pipe in his mouth.’ In fact, it was not Keats that he was invoking, but Milton’s description of the recently fallen Satan – ‘Archangel ruined’, yet retaining some of his angelic glory, ‘as when the sun new-risen/Looks through the horizontal misty air/Shorn of his beams’. It is a telling connection for FitzGerald’s subconscious to have made. Charles Lamb had adduced the same passage when he described the middle-aged Coleridge, a man broken by self-obstruction and opium but still possessing some vestige of the young genius whom Lamb had so loved and revered. Coleridge’s gifts were immense but imperfectly exploited. FitzGerald seems to have seen in Tennyson a similar case.

FitzGerald first read ‘The Lady of Shalott’ while an undergraduate, waiting for the night mail, and he never forgot it. Years later, he found himself reciting it aloud as he strolled in the Suffolk countryside. FitzGerald always believed in his friend’s genius, but he came to think that Tennyson had somehow gone wrong. ‘I despair now of Tennyson doing anything great,’ he wrote when the poet was still in his thirties. He attributed the failure to ‘self-indulgence and laziness’, of which that ‘inglorious pipe’ was a token. Only a few years later, FitzGerald’s despair had intensified into certainty. ‘He will never write Poetry again,’ he told a correspondent. ‘I mean such Poetry as he was born to write.’ And again: ‘I mourn over him as a Great Man lost.’ It is not obvious what the masterwork should have been. Nor is it clear exactly how much of this adverse judgement he communicated to Tennyson. He was clearly unfazed when Tennyson became an international celebrity – still prepared to advise abandoning Idylls of the King, a bestseller which he seems especially to have deplored. But Tennyson, normally hypersensitive to unfavourable criticism, seems to have taken such counsel in good spirit and continued to think of him as ‘dear old Fitz’.

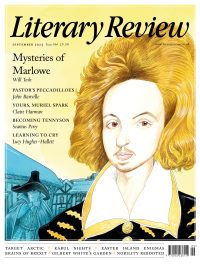

FitzGerald appears from time to time as a sort of touchstone in Richard Holmes’s vivid and extremely readable new book, in large part because Holmes’s view of Tennyson’s career is not so dissimilar to FitzGerald’s. The Tennyson he celebrates is the turbulent and wayward young man, not that ‘ancient Victorian bard with a tremendous beard’ – the figure of tamed propriety whom Joyce renamed ‘Alfred Lawn Tennyson’. FitzGerald thought that Tennyson’s best days were over by 1842, when he published Poems in Two Volumes, which does indeed include most of the great shorter poems. He didn’t think much of In Memoriam (1850), the long elegy that shot Tennyson to fame and the laureateship (‘Don’t you think the world wants other notes than Elegiac now?’), and his praise for the much-abused Maud (1855) was qualified (‘it is doubtless an original form of Poem’). Holmes writes incisively and with great admiration about In Memoriam, and he clearly relishes the touches of lurid psychodrama that flash through Maud, but this doesn’t really undermine the FitzGerald thesis, for many of the best sections of In Memoriam date from the years before its publication, and the first stirrings of Maud came about in a beautiful lyric, ‘O that ’twere possible’, written in 1833.

The poem was occasioned by the death of his friend Arthur Hallam, killed at the age of twenty-two by a stroke. It was by far the most consequential event in Tennyson’s life. Hallam is something of a challenge for the biographer. His charm and brilliance were celebrated by everyone – ‘when most bereavements will be forgotten,’ wrote Gladstone, ‘he will still be remembered’ – but the high-mindedness and rather arid intellectualism of his surviving writings are hard to make come alive on the page. The excellent Holmes does it very well, keeping in view both Hallam’s accomplishments (he was ‘self-assured, clever, and well aware of his blond good looks’) and his genuine kindness to Tennyson and his family, whom he seems to have been adept at cheering up. And there was a good deal of cheering up required, as the household endured the alcoholic tyranny of the Reverend George Tennyson, a talented man destroyed by disappointment. Holmes captures the barely suppressed hysteria of their isolated life, identifying in the early masterpiece ‘Mariana’ the ‘dream version of the rectory at Somersby’: ‘The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse/Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek’d’. The Tennysons often spoke of the psychological malaise arising from their own ‘black blood’. One of Tennyson’s brothers, Edward, spent most of his days in an asylum. Another, Septimus, memorably introduced himself as ‘the most morbid of the Tennysons’. A third, Arthur, was a drunk. Alfred, though the sort of man who could convulse the room with an impression of the sun coming out from behind a cloud, was aware of his own disposition to dejection. Hallam, assuming the air of a man of sound constitution, diagnosed in him an ‘extreme nervous irritation’ producing ‘incessant misery’.

The loss of Hallam was familial as much as personal, for he was engaged to Tennyson’s sister Emily, and the poet spent seventeen years writing lyrics about it before gathering the pieces together to make In Memoriam. The success of the 1842 volumes had ensured that Tennyson was well known, but In Memoriam made him a star. It is one of those rare works, like The Waste Land, that appear to articulate the feelings of an epoch. ‘It is rather the cry of the whole human race than mine’, Tennyson himself once said. Part of the poem’s currency, as has often been observed, is its deep immersion in contemporary scientific writing, and here Holmes, author of the widely praised The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science (2008), is in his element. Indeed, Tennyson’s various scientific passions are brought to the fore in this book. His early exposure to Marcet’s Conversations in Chemistry and Bewick’s History of British Birds anticipated his later interest in Lyell’s The Principles of Geology, Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation and the astronomical writings of Herschel and Whewell. The proliferating worlds made visible through the telescope and microscope were removing man from the centre of things; the world was being redescribed as a place of extinction and catastrophe, ‘red in tooth and claw/With ravine’. A new bewilderment was created by the awful disjunct between human and geological time: ‘The hills are shadows, and they flow/From form to form, and nothing stands.’

The bulk of this evocative and sympathetic book is a celebration of the young poet, but it ends with some pages about the fading away of this troubled, charismatic genius as respectability came. In Holmes’s sprightly phrase, ‘the beard made him a Victorian’. An intensely private and fraught creativity was replaced by the public duties of the laureateship, and imperial politics supplanted science as his abiding interest. This was ‘the safe direction in which Tennyson’s popularity’ expanded, and I suppose few would deny that the later Tennyson was a tamer beast. But I think the beast was still there, visible in ‘Enoch Arden’, ‘Lucretius’ and many passages in Idylls of the King. The close of this book reminded me of the excitement felt when, having devoured Holmes’s dazzling portrait of the young Coleridge (published in 1989), we anticipated the concluding volume. We were rewarded for our wait with Coleridge: Darker Reflections (1998), a brilliant study of the strange tenacity of genius in the most unpropitious and middle-aged of circumstances – a portrait of ‘an Archangel a little damaged’, to invoke Lamb. I suspect a second volume dedicated to the later Tennyson might show something similar.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

Few writers have been so eagerly mythologised as Katherine Mansfield. The short, brilliant life, the doomed love affairs, the sickly genius have together blurred the woman behind the work.

Sophie Oliver looks to Mansfield's stories for answers.

Sophie Oliver - Restless Soul

Sophie Oliver: Restless Soul - Katherine Mansfield: A Hidden Life by Gerri Kimber

literaryreview.co.uk

Literary Review is seeking an editorial intern.

Though Jean-Michel Basquiat was a sensation in his lifetime, it was thirty years after his death that one of his pieces fetched a record price of $110.5 million.

Stephen Smith explores the artist's starry afterlife.

Stephen Smith - Paint Fast, Die Young

Stephen Smith: Paint Fast, Die Young - Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon by Doug Woodham

literaryreview.co.uk