David Wheatley

Rhyming for England

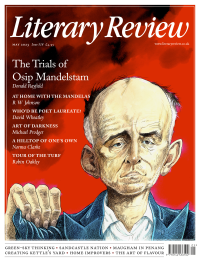

Sleeping on Islands: A Life in Poetry

By Andrew Motion

Faber & Faber 320pp £20

It all starts with a Rupert Brooke complex. One summer Andrew Motion and his fellow sixth-formers take off for Skyros, where the future poet laureate plans to track down Brooke’s grave. Some sun-baked wanderings later, the white sarcophagus is located. It is a strangely anticlimactic moment: no poetry is recited in this ‘corner of a foreign field’, not even ‘The Soldier’. ‘I wanted something more exalted,’ declares a disappointed Motion.

Back at home, he is surprised to learn that Brooke’s literary executor, Geoffrey Keynes, lives nearby. Soon he is staying over at Keynes’s house, where his host pulls back the sheets in the morning to admire the young man’s legs. Motion is not vocally perturbed by this, then or now. Perhaps this is the price to be paid for close access to the poet’s shade.

The fairy-tale quest continues at Oxford, where Motion encounters the elderly Auden, who stations himself by a Hockney painting of a naked youth before asking him ‘what [he’d] like’. A martini, Motion tells him, before realising something else might be on offer. The Newdigate Prize and some useful connections in the bag, Motion swaps Oxford for a lectureship in Hull and gets to work on cultivating its famous librarian.

The Philip Larkin encountered by Motion is the torpid, post-High Windows figure, drinking two or three pints over lunch, then falling asleep in his office. He jokes about his habit of ending letters with ‘fuck Oxfam’, to squirming embarrassment on the part of Motion – who notes, not entirely believably, that the crudities he later unearthed in Larkin’s letters came as a complete surprise. Lecturing is a struggle: the suggestion that he teach some novels bumps up against the fact that Motion has apparently never read any.

Sleeping on Islands is subtitled ‘A Life in Poetry’, but this is a book about Motion’s career rather than any kind of ars poetica. His time at Hull crystallises round a moment of epiphany on lonely Spurn Point.

Soon he is decamping to the capital to edit the Poetry Review and the Chatto poetry list. Here he would have ‘a greater chance to champion the diverse causes I believed in’, he says in the committee-pleasing tone he often adopts when discussing his projects. Going freelance, he fails to sell a biography of Elizabeth Bishop to Chatto (her executor won’t allow it), only for Carmen Callil – in one of this book’s many Lucky Jim moments – to offer him a contract to write a Lambert family biography instead.

In 1998, Ted Hughes dies and, sensing a now-or-never moment, Motion steels himself for a tilt at the laureateship. When news of his appointment is leaked ahead of schedule he feels ‘skinned alive’ by the resulting barrage of telephone calls. Yet on he goes, throwing himself into the awful but cheerful round of ‘readings, readings, readings’ and ‘talks, talks, talks’. Meeting Motion in Downing Street, Tony Blair greets him with a cheery ‘’Ello’, before opting for formality once he hears the sound of the new poet laureate’s voice. ‘It made me wonder whether Blair had any fixed personality at all,’ Motion says.

As laureate, Motion too becomes chameolonic, turning out topical effusions but reverting to safe-pair-of-hands mode for his elegy on the Queen Mother, and losing it altogether in his much-ridiculed rap lyric written for Prince William’s eighteenth birthday – dismissed here as an ‘act of self-sabotage’. Encounters with royalty arrive in the form of a weekend at Sandringham with Prince Charles, where a ‘pint of gin’ is pressed into Motion’s hands, before he is let loose on a throng of ‘luvvies and their partners’. The Queen herself is blandly dutiful (‘I’m afraid I don’t read much poetry’).

Motion’s acceptance of the laureateship was a calculated risk. Many great writers have been poet laureate, but history has not been kind to those remembered exclusively for their time in that role, such as the hapless Alfred Austin. On demitting his post in 2009 – though not, as he claims, becoming the ‘first ex-laureate’, an honour that goes to Dryden – Motion is thrown into crisis, unable to let go. Far from enjoying his freedom, he takes on yet more committee jobs and honorary presidencies, unsure if his identity is now stuck in civic mode or if he isn’t just ‘anxious that if I said no to anything, I might disappear from view’.

In the closing sections, there is a change of direction, a transatlantic trip yielding a job offer in Maryland. Unexpectedly, the most affecting piece of writing in Sleeping on Islands turns up at the end. In Baltimore, Motion and his wife encounter an elderly couple called Andrew and Joanna (the name of Motion’s first wife) on the porch of a neighbouring house. The arrival of the pandemic prevents any socialising and soon Andrew is being removed by ambulance from his house, dying of Covid-19 in hospital. Motion imagines the ghost returning home: ‘he can’t wait to settle down among his old things, to stretch out his legs and make himself comfortable.’ What if secret Andrew has been right all along and real life happens far from prize committees and royal receptions – in the Spurn Points of the world, where disappearing from view is not a punishment but a pleasure? As another familiar ghost might observe at this point, ‘Ah, solving that question/Brings the priest and the doctor/In their long coats/Running over the fields’.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

In 1524, hundreds of thousands of peasants across Germany took up arms against their social superiors.

Peter Marshall investigates the causes and consequences of the German Peasants’ War, the largest uprising in Europe before the French Revolution.

Peter Marshall - Down with the Ox Tax!

Peter Marshall: Down with the Ox Tax! - Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War by Lyndal Roper

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet double agent Oleg Gordievsky, who died yesterday, reviewed many books on Russia & spying for our pages. As he lived under threat of assassination, books had to be sent to him under ever-changing pseudonyms. Here are a selection of his pieces:

Literary Review - For People Who Devour Books

Book reviews by Oleg Gordievsky

literaryreview.co.uk

The Soviet Union might seem the last place that the art duo Gilbert & George would achieve success. Yet as the communist regime collapsed, that’s precisely what happened.

@StephenSmithWDS wonders how two East End gadflies infiltrated the Eastern Bloc.

Stephen Smith - From Russia with Lucre

Stephen Smith: From Russia with Lucre - Gilbert & George and the Communists by James Birch

literaryreview.co.uk