David Wheatley

Sex was a Mystery to Him

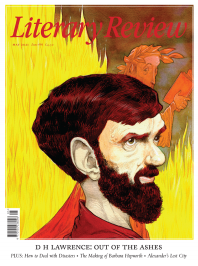

Burning Man: The Ascent of D H Lawrence

By Frances Wilson

Bloomsbury 479pp £25

Half a century ago Oliver Reed and Kate Millett each had a career-defining moment involving D H Lawrence: Reed when he played Gerald in Ken Russell’s 1969 film adaptation of Women in Love, with its celebrated wrestling scene, and Millett the following year, when she staged one of the great critical assassinations of Lawrence, in her Sexual Politics. Reed’s character in Women in Love feels humiliated by Gudrun’s attacks on his masculinity, tries to kill her and ends up slipping into a snowdrift, where he freezes to death. Reed had his own well-documented problems with toxic masculinity, notably when his encounter with Millett on Channel 4’s After Dark descended into a drunken assault. I wonder how much distance there is these days, in the public mind, between Reed’s brainless aggression and Lawrence’s patriarchal dogmatism, so memorably skewered in Sexual Politics. For decades now, Lawrence has endured a reputational deep-freeze. Frances Wilson’s attempts in Burning Man to bring him in from the cold show bravery and steely determination.

The similarities between Lawrence, the congregationalist son of a Nottingham coal miner, and Dante may not be immediately apparent, but Wilson has chosen to model her book on the tripartite form of the Divine Comedy. Lawrence’s inferno is England, 1915–19, when, newly married to Frieda von Richthofen, he writes The Rainbow before coming to realise that England cannot hold him. Purgatory is Italy, 1919–22, where he does some of his best travel writing and begins to use his fiction more self-consciously as a platform for his theories of life. Paradise comes in the form of New Mexico, to which he is invited by Mabel Dodge Luhan and where his ‘savage pilgrimage’ finds its deepest expression, even as the tuberculosis that will eventually kill him in 1930 tightens its grip.

If provocations were principles, Lawrence would be the most moralistic of modern writers: whatever the occasion, he is ready, with his natural mix of insecurity and exhibitionism, to pounce with a slogan. Remembering his mother’s desperate frustrations with her heavy-drinking husband, Lawrence tells Jessie Chambers that it is the man who ‘pays the price in life … not the woman’. If there is one thing worse than a hidebound feudal society it is equality, against which he rails unendingly. He visits Bertrand Russell in the not notably egalitarian setting of Cambridge and, having held his own at high table, is reduced to homophobic nausea by the sight of John Maynard Keynes in pyjamas at noon. In Sea and Sardinia he is scathing about the rise of fascism, but sees any socialist alternative as a wicked abstraction. His quarrels with Frieda frequently descend into ugly brawls, with an unmoved Katherine Mansfield noting how she ‘never did imagine anyone so thrive upon a beating as Frieda’. Inured to disappointment by British publishers, Lawrence cultivates a garish line in invective, the principal job of which is to remind us that Lawrence is always right and the world at large wrong (the editors at Heinemann are ‘blasted, jelly-boned swines, the slimy, the belly-wriggling invertebrates, the miserable sodding rotters, the flaming sods, the snivelling, dribbling, dithering palsied pulse-less lot that make up England today’).

Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda. The pendulum swings between denial and near acknowledgements of his bisexual side are a painful spectacle, though warm-weather climates allow for a certain unbuttoning impossible on native soil. Perhaps the prime example of this involves the text proposed by Wilson as Lawrence’s masterpiece, his little-known introduction to Memoir of Maurice Magnus. His involvement with this now-obscure littérateur – sometime French Legionnaire and full-time genial sponger – is one of the strangest chapters in Lawrence’s life. Normally a workaholic, Lawrence loafs around in Magnus’s company, lending him money, drinking whisky and coming as close as we ever see in this book to outing himself. When Magnus’s creditors catch up with him, he swallows prussic acid. Lawrence settles his account with his dead friend by publishing his memoir, adding a catty pendant of his own. The case for a reprint (and how much of Lawrence is out of print now!) must be strong.

It is typical of late Lawrence that, stopping over for three months in Australia while en route to New Mexico, he finds time to pour out the long novel Kangaroo. As the clock winds down, his energy ramps up to well-nigh demonic levels. Life on the pueblo in Taos turns on a typically Lawrentian inconsistency. With her native American husband, Tony Luhan, Mabel Dodge Luhan would seem to be a fellow traveller of Lawrence’s, equally disillusioned with modernity and striving to reconnect with more chthonic forces. Yet Lawrence reacts to her with something between scepticism and fury, berating her for her saviour complex and urging her to overcome her ‘poisonous white consciousness’. At the same time his own sense of connection with native American culture falls curiously flat, and he finds the Pueblo Indians to be ‘without any substance of reality’. Wilson ascribes the failure to Tony Luhan’s mockery of Lawrence’s physical puniness. One positive outcome, at least, of all these mental dramas is Studies in Classic American Literature, still among the most readable of his books. When Mabel is transmuted into fictional form (in ‘The Woman Who Rode Away’ and ‘None of That’), however, the results are among the ugliest pieces of misogyny in the Lawrence canon. The addition to the ménage of the painter Dorothy Brett raises the emotional intrigue to still dizzier heights. Wilson’s story breaks off in 1925, five years before Lawrence’s death, passing over the final drama of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, though she does give us the farcical tale of the repatriation of Lawrence’s ashes to Taos by Angelo Ravagli in 1935. Depending on which version we choose to believe, these were either dumped in Marseille, mixed into the cement base of his Taos altar stone or ceremonially eaten by Frieda, Mabel and Dorothy.

Wilson’s Guilty Thing, her life of Thomas De Quincey, is one of the finest recent literary biographies. Partial portrait though it is, Burning Man is in the same league. Few readers will be converted to Lawrence’s authoritarian phallocracy, thank goodness, but then it was Lawrence himself who insisted we trust the tale and not the teller. That may be a strange note on which to end a review of a biography, but this is a book that performs a rare and laudable task: of saving a writer, posthumously, from himself. We are all beneficiaries of Wilson’s articulate and persuasive advocacy.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

How to ruin a film - a short guide by @TWHodgkinson:

Thomas W Hodgkinson - There Was No Sorcerer

Thomas W Hodgkinson: There Was No Sorcerer - Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops by Tim Robey

literaryreview.co.uk

Give the gift that lasts all year with a subscription to Literary Review. Save up to 35% on the cover price when you visit us at https://literaryreview.co.uk/subscribe and enter the code 'XMAS24'