Kevin Jackson

Enfant Terrible

Jean Cocteau: A Life

By Claude Arnaud (Translated by Lauren Elkin & Charlotte Mandell)

Yale University Press 1,014pp £30

It is almost half a century since the last full-length English-language biography of Jean Cocteau was published, and it has taken thirteen years for Claude Arnaud’s work finally to be translated from the French. There are, no doubt, sound financial reasons for this. Although the elderly Cocteau of the 1950s and early 1960s was famous from Germany to Japan and from New York to Lebanon, the only fragments of his large oeuvre much known in the Anglophone world these days are two feature films, Orphée and La belle et la bête, and a brief novel-turned-film, Les enfants terribles. Are we wrong to neglect him? We are. Arnaud’s eloquent and loving portrait of his hero should persuade all but the most dogged of Cocteauphobes that we are denying ourselves a great deal of pleasure.

Even if Cocteau had confined his career to film-making, he would have a solid claim to posterity’s gratitude. Orphée was, and remains, unparalleled as a triumph of freewheeling imagination over sparse means: no director before Cocteau had ever had the audacity to shoot a scene in a bare, ruined room and tell us that it was Hell, and none had possessed the charm to make such a Hell not merely convincing but also beautiful. A list of the film-makers who learned from Cocteau would have to include Almodóvar, Kenneth Anger, Antonioni, Bertolucci, Carax, Joe Dante, Maya Deren, Godard, Derek Jarman, David Lynch, Paul Schrader and Andrei Tarkovsky. Along with his countryman Jean Vigo, he is one of the best teachers of how films made with the most modest of resources can still aspire to greatness, and sometimes attain it.

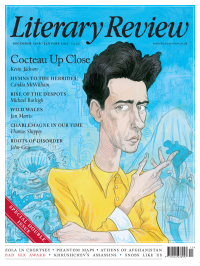

Impressive though this is, Cocteau is more, much more than just a cineaste. He came to cinema quite late in life – he was approaching sixty when he made his two most famous films – and before that time had put his swift mind and expressive hands to many other arts. He was a poet, a playwright, a set designer, a theatre director, a novelist, a travel writer, a librettist, a jewellery maker, an actor and an autobiographer. There is a famous trick photograph by Philippe Halsman, used on the cover of Arnaud’s book, that shows a six-armed Cocteau, like a chic Parisian Vishnu, wearing a reversed coat of his own design and holding a book, a pen, a pair of scissors, a cigarette…

Combined, his many talents brought him early fame. Ezra Pound said that Cocteau was the best writer in Europe, and in the 1920s he was the figure who at once presided over and epitomised the miraculous, jubilant Paris of les années folles, luring rich patrons and hard-up artists to the most exciting nightspot in town, Le Boeuf sur le Toit, teaching them to love the high life of jazz and cocktails (often referred to as Coct-ails) while bashing away gleefully on a drum set. The final coup of his first, dazzling period came in 1930, with the staging of La voix humaine, which thrilled almost everyone. With the single exception of one play, La machine infernale, he did not fare nearly so well in the later 1930s or during the occupation, when he seemed to be far too chummy with the more cultivated members of the German army. His wartime actions and inactions – on the whole fairly blameless, or at any rate no worse than those of other Parisian artists – damaged him for years to come. For a while, he even lost his audience among young people, and it is sad to read that on its first French release Orphée was an unmitigated flop.

A rebirth of fame would eventually come to him when he was becoming too frail fully to enjoy it. Through many years of neglect, he consoled himself with the memory of a remarkable feat: despite his origins as an esoteric Symbolist poet, he had won the love of the public for more than a decade. He could never forget, though, that many Parisian intellectuals did not join in the mass adulation. In fact they regarded the multifaceted nature of his output as proof that Cocteau was really no more than a dabbler, a flimsy butterfly of a talent who hopped from art to art without ever achieving more than at best prettiness and at worst sugary kitsch. His enemies were influential, and this dismissive view became a standard one. But Arnaud contends that his subject, far from being a featherweight Jean-of-all-trades, was closer to the Universal Man adumbrated by the likes of Ficino. Cocteau is not, Arnaud concedes, quite in the same league as his difficult friends Proust, Stravinsky and Picasso, but he is not as far beneath them as most people assume.

In some respects, Cocteau’s is a riches-to-rags story. He was born into a prosperous Catholic family and was greatly indulged by his mother. Like Proust, Cocteau was one of the most extreme cases of a maman’s boy in the world of French literature; his father died when he was young, and Cocteau did not leave his mother’s house until he was thirty-seven. Later in life, partly because of his long-term addiction to opium, he was often painfully poor, living in cold, squalid single rooms, seldom washing, dressing in tatters and eating so little that his body, always slender, came to border on the skeletal. He was fortunate enough to have a few rich friends who, from time to time, would offer him pleasant places to stay and good food (Coco Chanel was one of the most loyal), but even in his times of fame he seldom earned an adequate income. The older he grew, the more envy he felt for the now-wealthy Stravinsky and the monstrously wealthy Picasso – neither of them always good to him.

Cocteau suffered other ills, just as crushing in their way as poverty. Arnaud writes of his ‘fevers, hay fever, stomach cramps, facial tics, skin diseases, sciatica and crippling jaundice’, and that is only part of the sad story. Although he hid his homosexuality from his mother for many years, he might well have found the Paris of the 1920s a fairly agreeable place to be gay, had it not been for the Surrealists, who, at the behest of their dictator, André Breton, persecuted him viciously for two decades. They heckled and threw stones at the premieres of his plays, they phoned his nervous mother to tell her he had just died in a car crash, and one of the gang, Robert Desnos, attempted to kill him. Part of their hatred was aesthetic – they thought him a reactionary trifler and plagiarist of other artists’ visions – but Arnaud’s account makes it clear that the real motive was Breton’s pathological hatred of gay men, especially the ‘sissy’ kind. After the war, most of the former Surrealists were happy to bury the past and be friends with Cocteau. Breton continued to loathe and spurn him.

One of Arnaud’s major themes can be put very simply: Cocteau was an exceptionally kind man and he suffered for it. (This biography could be used as a lengthy confirmation of the glib-sounding but useful proverb that no good deed goes unpunished.) Again and again, Cocteau identified and nurtured younger talent, either in the manner of a PR master or as a modern-day Pygmalion. His protégés included the group of classical composers known as Les Six and a champion black boxer, Panama Al Brown. Lee Miller, invoking an African variant of the Pygmalion figure, said that he had a ‘Cophetua complex’.

His leading Galatea figures were the novelist Raymond Radiguet (who died at twenty, leaving behind two remarkable novels), Jean Marais (a clean-limbed gay beauty whom he transformed into a heart-throb movie star for young girls, and also a serious actor) and the criminal-turned-writer Jean Genet, whose posthumous fame far exceeds that of his patron. Not all of his protégés spat on the delicate hand that fed them, but a lot of them did, and Cocteau found it excruciating.

Arnaud’s biography is very long (over a thousand pages, including index), but it seldom feels padded. His style – rendered into English with, he notes, some help from Donna Tartt – is as lyrical as it is ungrammatical, and he allows himself moments of speculative excess that will strike many readers as silly: ‘Some days he was so full of joy that he looked like a fetus daubing the wall with his placenta.’ Over the top, to be sure, and yet quite well suited to his flamboyant subject. Jean-Luc Godard once wrote an article in praise of Cocteau that repeatedly asked, ‘When did you last see Orphée?’ The triumph of Arnaud’s work is that it makes you keen not just to watch that great film again but to explore the whole of Cocteau’s delicate, fascinating universe.

Sign Up to our newsletter

Receive free articles, highlights from the archive, news, details of prizes, and much more.@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

The son of a notorious con man, John le Carré turned deception into an art form. Does his archive unmask the author or merely prove how well he learned to disappear?

John Phipps explores.

John Phipps - Approach & Seduction

John Phipps: Approach & Seduction - John le Carré: Tradecraft; Tradecraft: Writers on John le Carré by Federico Varese (ed)

literaryreview.co.uk

Few writers have been so eagerly mythologised as Katherine Mansfield. The short, brilliant life, the doomed love affairs, the sickly genius have together blurred the woman behind the work.

Sophie Oliver looks to Mansfield's stories for answers.

Sophie Oliver - Restless Soul

Sophie Oliver: Restless Soul - Katherine Mansfield: A Hidden Life by Gerri Kimber

literaryreview.co.uk

Literary Review is seeking an editorial intern.